At Milton Academy, this shit-ass boarding school I went to up in Milton, there was a kid named Paul Mackie. Richard and my mom had started having problems by the time Paul Mackie killed himself. I hadn’t seen my real dad in over four years, he disappeared before anyone could ask him to pay for a therapist or a Subaru. My mom said she always knew he had money but he didn’t. Being poor was more humiliating than being a deadbeat.

I didn’t go home for Christmas that year, and everyone acted like it was because I had plans at school. The truth was nobody was around. My Episcopalian girlfriend flew home to Maryland. I was alone. I collected pine cones from the golf course and brought them back to the empty room. I took some books off my roommate’s shelves and piled them on my bed. It snowed, and the radiator whistled. Dickens-type stuff. The week campus closed I went down to The Hope Inn and watched television. My mom called my dorm room on Christmas Eve. She left a message asking me if I was warm enough.

About Paul Mackie. This kid, man. He was good-looking and incredible at tennis but also super weird and none of us were that close with him. He was ridiculously funny on occasion. He had this thing where he was trying to beat his own record at how quickly he could come from jerking off and he would just announce it in the morning at breakfast, he’d lean over to you while you were spooning pale scrambled eggs onto your plate and he’d say, real quiet and slow, thirty…four…seconds, and you’d smile and he’d wink and take the white scrambled egg spoon from your hand and that would be that.

We were fourteen and fifteen and there was something both darkish and also child-like about it. Because most of us were either having sex or trying to have sex at every turn, and there Paul was, beating off with the newfangled exhilaration of a twelve-year-old.

There were rumors that Paul’s uncle had fingered Paul’s asshole and concurrently jerked himself off when he was a kid. Probably Paul had started the rumor. There was nothing that made sense about the kid. He wasn’t Florida-weird enough to be a weirdo or just slightly strange enough to be a future art teacher. He was just off, in a way that didn’t make sense except to not scare you but also not make you want to get much closer. He said the things aloud that you thought to yourself, but at that age you didn’t applaud someone for being honest. He once said to me and some other guys, Why is it that when we get our hands on something with a funky smell, like pussy or our own ass crack, we smell only the back of our hands, the fingernails? We bring our hands up like this, fast, and just smell the top? Like it’s less gross that way.

The group of us all solemnly and individually agreed but outwardly we smiled and said, You’re a fuckin nutjob, Mackie.

As the year progressed, Paul started to crack. By late November he was eating alone and skipping morning meeting. He also always had a yellow legal pad on him, and a pencil. He scribbled a lot, left-handed, even though we were pretty sure he used to be a righty. He talked in the hallways to himself. We’d never seen him in the showers, he’d never gotten naked around anybody, as far as anyone knew, but now we’d see him occasionally come wet-haired from the field house, wearing clothes over his damp body, like he hadn’t toweled off.

I’m sure at one point we, each of us, wanted to go up and say something. But we were young and so much was going on in our lives. I for one was dating a girl with a family that let me sleep in the same room as her when I visited. My buddy Hudson and I were writing a business plan for something we were super excited about for sixteen days. We were playing lacrosse, taking three showers a day, doing homework, hiding Japanese whiskey under beds, making fun of the Korean kid down the hall who ate out of a stone bowl. Outside as far as the eye could see girls walked on legs straight as field hockey sticks with little curved feet, skirts were woolly and fresh, everybody was totally healthy and our lives were laid out ahead of us exactly as we’d been promised.

What made everything worse was Paul didn’t have a roommate because the kid dropped out the fourth day, so nobody knew what Paul did in there. One night after everyone came back from the holiday, the prefect was on a date so Heinz the fat German kid was hosting a party in his room. I was drinking a beer and watching everyone act totally carefree. At some point I went and knocked on Paul’s door. Come in, he said, after a very long time.

I opened the door and he was on his bed, hands folded across his chest like a goddamned vampire, looking right at me.

How are you this evening, Hurt?

Heinz has a 30-pack in his room. Julia and the French chick already made out. You should come down.

Appreciate the invite buddy, but I’m working. Twenty-six seconds.

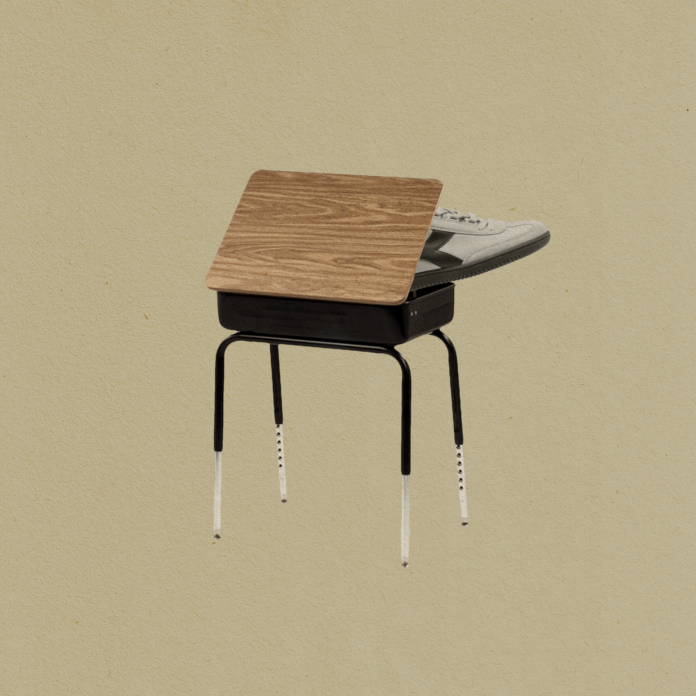

He had these really nice cordwain high-top sneakers on, that I’d never seen before. He was wearing them on his bed, which wouldn’t have been weird except for the fact that he was in boxers and a t-shirt.

Nice kicks.

Thanks.

Okay so if you change your mind, come down.

Ten four.

I started backing out and closing the door behind myself when Paul said, Hey buddy?

Yeah?

You have a soul. Remember when the world Dutch-ovens you, that it’s better that way.

Okay, Paul.

I closed the door and went back to Heinz’s room. Julia and the French chick were toplessly rubbing chest against chest, their medium-sized tits plastic-bubbling against each other and the guys were quietly hooting from bunk beds and computer chairs and two nutless creatures whose names I never learned were playing cards on the burgundy carpet stained with beer and cratered with cigarette burns from the long winter. Heinz lit a fart on fire. He had the pinkest cheeks and looked like he’d live, fat and happy, till 90. Durgan, this freak from North Carolina, was throwing back White Castle cheeseburgers, saying, Fuck man binge eating on weed is like hate-fucking your mouth! Julia and the French chick stopped making out for the sake of the boys and started doing it because it felt good. A girl named Charles put her hand on my boner and held it there and the girl I was dating, the Episcopalian, came in unexpectedly and acted like nothing was going on, and Charles removed her hand and everything was fine.

That same night, I got a call from my mom. Not in my room, but on the hall phone. She said she was bleeding. That’s all she said. She said, Will, I’m bleeding. I was a little basted, weed and beer and just the general godlessness of a room party—all that hot breath and angst and loaded dicks—so I said, What? Like almost laughing.

I’m bleeding. Richard is leaving me. And I’m bleeding.

Her voice sounded like water. I yelled for the precept first, then I hung up on my mom (as I said, I was stoned) and dialed 9-1-1. I used to think that was something only poor kids did. Of course, I would soon become poor. I would revert to being my father’s son. That’s the thing about stepdads. They can be real douchebags, and they won’t regret it in their veins.

I called my mom back and she didn’t pick up. I called the police station in our town and they said someone was probably on the way. Eventually our entire floor had congregated around me in the hallway. All the dudes had purple dots for eyes, all the girls had messed up hair, terrific static cling.

I was crying. I kept hanging up and calling back and hanging up and calling back. I’d drop the phone down on the receiver instead of just pressing the bar with my finger. I don’t know why. I was aware of my drama, it felt good to do something a little dramatic, a flourish.

What I’d find out later was that Richard had told my mom he was thinking of leaving her for a stripper. Not like a real slutty one, but one who didn’t take her bottom off and worked at a place called The Inn of the Frogman. All classy and such. That was the fucked up thing about Richard. He said he was “thinking” of leaving her. He was always doing shit to try to get people to perform for him, like monkeys. My dad might have been a deadbeat, but listen. He wasn’t a fucking twat.

And honestly during the whole Richard period, my mother turned into, I guess you might call it, the person she had always been. That’s the problem with parents. They want to be themselves before they want to be your parents. Even so, you get all gutted when you hear about some diamond thing they did for you, after you spend a lifetime hating them for the shit that adds up. Like for all the times they left you in skiing daycare with rough mountain broads. All the times you cried to be held by your momma and you got a babysitter with a hairlip instead. For example, there were some pretty big things my mom did for me, that I didn’t know just then. An abortion, for example, earlier that year.

Charles was holding my shoulder, and the Episcopalian was twirling her light brown hair around and around her index finger. I felt bad for the Episcopalian. She would never know real love because her parents weren’t shitty enough for her to never go home. Sometimes it’s better to be like me, and come from true garbage.

But that night I didn’t think of it like that. I could only think of my mother, the dryness of her hair, the way her hands always smelled like bleach until one day they smelled like Rodin. I was thinking of when I was little, we used to have our weekly alone nights, though she called them Cub Dates. We’d been eating Chinese and seeing something funny or scary at the Angelika, every Wednesday since the end of my father. It was the one night a week I could count on. Like all clung-to bits of time, Wednesday colored every other day of the week. Tuesday was almost better than Wednesday, because Wednesday went too soon. Thursday and Friday were dark, and of course the dread of Wednesday at bedtime, when I knew for a whole week my mother would be a pod person. A Richard apologizer. She’d wear the green slip to bed and close their bedroom door, a broad piece of pine that slid shut like an elevator.

We always went to this dumpling place on the Tribeca crust of Chinatown. It was all blond wood and they had Boylan’s colas and laughing families. You could see the cooks in the open kitchen. They worked quickly, sizzling bright peppers and garlic, and looked serious but kind. Behind them, a wall of steel shone like hammers. What are you getting, Cub? she’d ask from behind her menu. I was always making sure Richard wasn’t around, so I could let my guard down. I always saw men at other tables watching my mom. She was really a stunner. Long, black hair and big, sky-colored eyes. Stunner was what my dad called her, before he never did anymore. I wondered for a while if it was because she had stopped being beautiful just to him, or in general. Certainly, she never stopped being beautiful for me.

Pork and crab dumplings, I said. That’s what I’m getting, she said. We used to get the same thing before Richard. After Richard, everybody had to get something different, so he could sample as much of a menu as possible. The universe was changed, after him. My mother used to be a woman who upended jugs of detergent to catch every last blue gloop. After she married Richard, she stopped trying to catch the drops. She still rolled up tubes of toothpaste, but tossed them when they yet had some life inside. The worst thing was, she was always telling him things about me as though he weren’t the enemy. This one night I took her hand and rubbed it during dinner, forcing her to eat with just one. I was always trying to leave my mark on her. I felt like she knew that, and it made her happy. She had to love me more. I told her how I really felt about him, about Richard. I don’t know, I guess I thought she’d leave him and we’d move into a studio in Morningside Heights. Or even Inwood.

But she didn’t leave him and I guess she told him. She had to have. The next year he talked my mom into sending me to Milton. In my best interests, and what not. But just then, at the table, she promised she wouldn’t tell him. She slit into her soup dumpling, the slippery night-colored juice streamed out, and I believed her. We ate in silence then ordered dessert. Chocolate ice cream in a silver cup. Colder than it was good. How could I know that while she sat there, idly mowing Martian paths through the ice cream with her spoon, that she was making the decision to choose Richard over me?

But I didn’t know, is the point. I didn’t know until that night she called and told me she was bleeding. Even then, I didn’t know for sure until later. At that point, I was just shaking and saying, over and over, Please God Help My Mom. Please God Help My Mom.

An ambulance came in time to save her. And Richard, I guess, felt like she’d done enough to prove her fealty. So he decided to stay. Or maybe the stripper—her name was Cleo, I know because I looked her up over Easter and took her to bed—rejected Richard first.

But anyway that night I learned two things: one, that I was utterly alone, and two, that I wasn’t really alone. Paul Mackie left me a note, under my door. The handwriting was really slippery, like kindergarten Gothic, and I had to read it three times to be sure of what it said, but I think I got it.

Hurt,

There is no home. None of us has one. Look at all the best men. They lived nowhere, or else in hotels. You think Gandhi had a fucking electric can opener?

Paul

Six weeks later Paul Mackie stood up on the bench of a lunch table and said, loud enough that pretty much everyone could hear, THIR-TEEN SECONDS. Later that night, he hung himself from the holey rafter in his room. The prefect found him and shrieked like a young lady, so a bunch of boys semi-circled the doorway. Paul was naked except for the brand new sneakers, laced to the top. His hair was gelled back like a greaser and his eyes were closed. Apparently, there was a smile on his face. I didn’t see him but Hudson did. He was trying not to cry when he said, Man, Paul Mackie had, like, the biggest dick, that I’ve ever seen.