Marlon — who had given her that name? She didn’t like to talk about her parents. “I don’t pay you enough for that,” she said once. She was frank to the point of seeming humorless, but she brought the same short, even-keeled tone to every topic of conversation — dinner plans, national news — and that, in a way, was funny.

I was Marlon’s apprentice. She hired me because there was something alike about us, she said, but I couldn’t see it. We worked together in her apartment, where I drafted contracts and sent out mail. Marlon had been an editor at a major publishing house for over a decade before starting her own enterprise; now, among other projects, she was editing a book about the California wildfires. I sometimes heard her discussing chapter divisions with the author, Dr. Christine Mayer, a science reporter from Bakersfield. “Drift smoke,” Marlon would say, nodding and taking notes. “Windfall.” It was surreal, sitting in a high-up spot in Park Slope, looking across the street at a Dominoes Pizza, a Chase Bank, and thinking about helpless brush, piercing cracks. Where were we?

I’d been living with Owen on the other side of Brooklyn, too many connections away for the train, so I biked instead, even in January. This saved us money, which was something I was conscious of, because I was the one paying rent. We’d moved here together from Texas, and Owen was still struggling to find full-time work. He’d been picking up odd jobs that he found on Craigslist, on TaskRabbit. Once, he helped a corporate lawyer look for his glasses, which had been resting plainly on top of his pillowcase. (“Well,” the man said, handing him a fifty-dollar bill, “this is awkward.”) Mostly, he helped people move. Juggling the gigs was a job in itself, Owen said, but there wasn’t much else he could do; nobody wanted to hire him. I figured this was because he didn’t have a college degree. At home, this had never bothered me. Along with the rest of our friends, he was smart and a little slow-moving. Maybe he was smart because he was slow-moving. We would read aloud to each other, would have debates with no resolutions. Still, I realized after college that I wanted to do something next. I was always re-writing the sentences in his books — old books and comic books. “Quit it, bozo,” he would say, or, “what are you, an editor?” He’d meant this as an insult — why couldn’t I leave things be? — but I figured, hey.

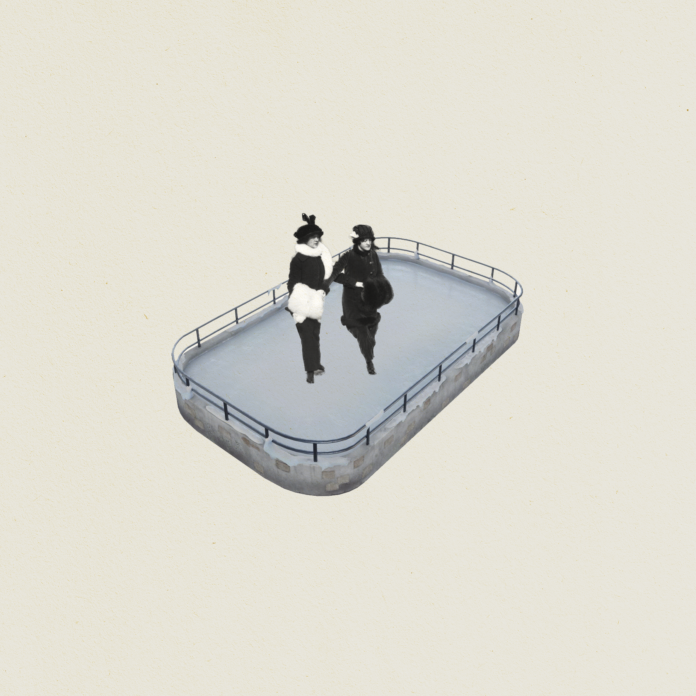

Although it’d been my idea to move, once we got here, it was Owen who settled in fast. Not logistically — it was something about his body. His shoulders never looked tense, even in the cold. On weekends, we went to the ice rink in Prospect Park and watched the junior hockey league. Owen could skate himself, and started giving the kids advice. This turned into a volunteer coaching position, which seemed promising. I would sit on a bench and watch him weave around with his hands behind his back. Circles and circles. Hypnotic, for me.

◆

When she had good news, Marlon brought in bagels. A neat, brown bag, unstained from grease. She would unpack them, mine then her’s, and we’d eat in the room that she was calling her office. It was lined in white shelves, color-coordinated books. On my first day I asked her how she ever found anything. “Easy,” she said, shrugging.

Usually, she would tell me about a promising pitch she’d received from an agent. Although she only published nonfiction books — memoirs and popular science with timely angles — she was sent romance novels, British capers, children’s fantasy. It was rare to get a suitable pitch, let alone a sellable one, she said. “Don’t ever write a book,” she liked to say. “There are too many books.”

One day, about six months after I’d started working for her, she told me as she unpacked our bagels that no, there wasn’t a new project to discuss. This news was different. She compressed the bagel’s paper and aluminum wrapper into a little ball and wiped crumbs from her shift dress — she was always wearing these shift dresses, even though technically she worked from home.

“I have a lot going on,” she said. “And your reader’s reports have been good.”

What she wanted was for me to be Dr. Christine Mayer’s “point person,” now that her book was close to finished.

“You’ll just be shepherding it to completion,” Marlon said.

This sounded vague to me, but there was something hopeful and even grand in its vagueness. I was used to success feeling more straightforward — a letter, a number, a puzzle piece fitting softly into place. I found that I preferred this more diffuse and interpretable sense of accomplishment. Whatever I was now, I was better than before.

“So,” I started.

“You can call it a promotion if you want,” Marlon said. “Titles don’t matter to me. Honestly, if you apply for other jobs, just tell me. You can use whatever title you want.”

“Okay,” I said, smiling. I wasn’t used to such broad acceptance.

Marlon explained that there’d be a raise, too; she wouldn’t ask me to do more work without more pay. I thought about the possibility of a Metro card, also of new sheets, and a shift dress.

“I don’t know what to say,” I said.

“So don’t say anything,” Marlon said.

She went to one of her shelves and, standing on her toes, reached for a pile of folders. She wore tights in the winter, but no shoes inside. She looked professional but unencumbered.

“This has everything,” she said, handing the folder to me. She explained that line edits were outsourced, and so was design. I’d just have to make sure that everything stayed on schedule, and to comfort Dr. Mayer if — and when — she got anxious.

“She’s low-maintenance,” Marlon said. “But all authors get anxious.”

All authors were also slow workers, Marlon said. It was our job to prod them, but gently.

Marlon had lunch plans with an agent; she slipped on her shoes and went out. Dr. Christine Mayer’s manuscript — Marlon’s plans for it and the thing itself — was heavy in my lap. I sat there with the weight of it and looked out the window. The nearest street corner was rounded out by a slope of snow, and walkers in their grey coats and hats took care to avoid it. The heater came on noiselessly; I only knew because I could feel it. I was conscious of appreciating how indoors Marlon’s office felt. At mine and Owen’s apartment, the pipes made abrasive hammering sounds, as if keeping itself warm was an effort. There were also mice.

I spent the rest of the day reading through Roaring Home, which turned out to be more ethnographic, more personal, than I had imagined. In her introduction Dr. Mayer wrote about her smoke-laden hometown, a city that was not frequently alight, but where, still, more and more people were developing asthma. Each chapter detailed a different Californian’s precarious sense of place, the looming threat of evacuation.

Marlon had been right; as far as I could tell, the book was almost finished. I was curious to know how formless it had been at the start, how it had come to take the form it was in now. I carried the folder with me from my chair to Marlon’s chair and sat down. It was a high-back, ergonomic swivel-chair. I sat upright, stretched. I put my palms on her desk, which was white and glossy, like an IKEA desk only somehow more substantial. She had a sprawling desk calendar, with lunches marked in green, dinners marked in blue, and phone calls marked in red. There were no family photos, but it didn’t feel impersonal. She had a bowl filled with matchsticks from different bars, and a framed snapshot of what looked like a fjord in Norway. On a floating shelf, she had all of the books she had edited, lined up in a row.

Her chair was more comfortable than mine. I kicked off and spun around, holding the folder to my chest. I kept spinning, then, hearing something, I stopped myself. Marlon was coming around the corner, was there in the room, was already mid-sentence, explaining about lunch, which had turned into drinks, then dinner.

“And I said, ‘that album was what, nine years ago?” she said. “What has he been doing since then?’”

“Oh,” I said. I hadn’t heard her come in.

Marlon moved to sit in my chair; she didn’t seem to notice my transgression, or else she noticed and didn’t mind.

“And he said — get this — that I’d be ‘lucky’ to sign this author. ‘Author.’ And I said, ‘okay, but who’ll write the book?’

Marlon had many stories like this. B-list celebrity memoirists seeking a deal, a ghostwriter; puffed-up agents who dismissed her as unserious.

She held up a finger, like, just a second, and went out the door. I heard her head upstairs; her place was like a loft, with small barriers and furnishings separating the kitchen, the bedroom. Only our work space was sequestered. I spun around in her chair again, and she came back panting with two wine glasses.

“Sam’ll be late,” she said. She sat back in my chair, perched on her ankles. “Drink with me.”

Sam was Marlon’s husband. I was always forgetting about him, because he was never around. I had met him once, though. He shook my hand and said, with some pomp, that it was so nice to meet me.

The agent had given Marlon a bottle of Merlot, which she unscrewed without difficulty. She said, using air quotes, that it had the right fullness for wintertime. I told her that I had read Roaring Home, told her also how grateful I was, truly, to help with the book. The introduction really worked, I said; it was essential, actually, otherwise such disparate chapters wouldn’t feel so well-connected. I was eager to impress her, but she just nodded, as though she was only half-listening. I realized that I must’ve sounded like a sycophant. Outside, it had started to snow, and we both stared in the direction of of a puddle that had started to ice over. It was illuminated by the Dominoes sign. Red-and-blue ripples.

“Hey,” I said, trying to change the subject, “where’s Sam?”

By this time I was on my third glass.

“I mean in general,” I said. “Or, maybe that’s worse. Maybe that’s not what I mean.”

“It’s fine,” she said. “But I couldn’t tell you, because I don’t ask.”

She said this glibly, like it was a joke.

“Does he travel for business?” I said.

I wasn’t sure what Sam did for a living. In my mind’s eye, there was an image of watches.

“Yes,” Marlon said. She tilted her head, as if to reconsider. “Sometimes.”

She was looking outside still. Perched on my chair like that, she looked like a child. Not naive, but calm and assured, the way some children are.

“This will probably sound strange to you, but I like it when he’s not here,” Marlon said. “It’s not that I dislike it when he’s here. It’s just that then I feel pressure to do things. Cook. It’s self-imposed, but he also doesn’t object. And it’s a part of myself I enjoy. But when he’s gone, I get to be the other parts of myself, too. Do you know what I mean?”

“Yes,” I said, although I didn’t. I had never, until that moment, imagined myself in parts.

“And I’m sure Sam feels the same way. There are parts of him that don’t belong to me.”

This was also hard for me to imagine. I didn’t think that Owen and I belonged to each other, but we felt inextricable. I wanted to know what Marlon meant, but I also didn’t want to seem unsophisticated, so I just nodded.

“You’re very wise for your age,” she said, pouring more wine.

“No I’m not,” I said.

“Don’t tell me that,” she said. “I just gave you a raise.”

Hearing her say it out loud again, I felt a rush of warmth. Then I checked her wall clock, and she noticed me checking.

“It’s late, isn’t it?” she said. “Go, go.”

◆

As I biked home, I thought of what I’d tell Owen about my promotion. It seemed unkind to share the news when he was in a rut himself, even though he tended to regard career advancements as pleasant happenstances, like found coins. We met while working at a bookstore near the college where I was a student. Owen hadn’t applied to college, but he was paying for his brother’s tuition at a neighboring trade school. He liked to look up professors’ syllabi and do the reading himself. It was as much about learning as it was about proving that he was capable. He would make a point to drop names and facts into casual conversation. Later, he figured out that those of us who paid tuition were nonchalant, and even embarrassed, about the knowledge we were gaining. It must’ve become clear to him that his efforts to educate himself wouldn’t affect his social life, so eventually his efforts waned a little, were re-directed. He left the bookstore job to work at a sporting goods store. He got some ice skates for cheap, and would play with a league three nights each week. When he came home, his hair was wet and frizzy and smelled like salt. I made him lie in bed with me before he got in the shower. After spending all day in my head, with characters imagined or historical, and so imagined in their own way, with abstractions and concepts, it was comforting to reenter the physical world each night; the result was a feeling of wholeness. We would lie around and talk — about whatever I was reading for school, or about strange customers, of whom he drew pictures on Post-Its — and then I would notice something about him that I already knew was there, like the raised spot on his bottom lip, not a mole exactly, or he would notice something, like the slope between my waist and hip, and there would be a faint acknowledgement (the word “hip,” maybe), and we’d have sex, and then, sometimes, he’d turn me over and we’d have sex again. After, I would feel the raised spot on his bottom lip against my back, and we would fall asleep.

At the time, I thought this was all there was to love. I was right, in a way; this was the part the rest grew from, the part, also, worth protecting.

I unraveled my scarves and worked my keys a little weakly in the lock. My hands were numb and red. I decided that I’d keep the news of my promotion to myself. It was my news, after all, and there were parts of me, as Marlon had put it, that didn’t belong to Owen.

Inside, it was dark. We shared a studio, and so far all we had was a table, two chairs and a mattress with no frame. We also had a Stanley Cup replica that Owen thought was funny. The space was too small for joke items, I thought, but it did double as a spot for our keys. Owen was asleep, lying on his side in the middle of the mattress. I’d forgotten that he got up early to watch one of his students play in their first game. I dropped my keys in the Stanley Cup, hoping that he’d wake from the noise, and he did.

“Nora,” he said. He rolled over slowly, patted the bed.

“Come here,” he said, although I was already beside him. “Tell me something.”

This was what Owen would say after I came home from class, from my internship at a literary magazine, from work at the bookstore. He’d listen to banal things attentively, like they were good stories, and I would too. Because the details of our lives were so different, we found ourselves talking about things that weren’t timely or related to achievement. The smells and sounds and shades of things.

Now, I found myself talking about Marlon’s drama with the agent, with the B-list musician, also about lunch, about nothing.

“Glad things are good,” he said.

“Things are things,” I said.

“Sometimes,” he said, half-asleep again already.

“No, hey,” I said, shaking him. “Tell me something.”

“Carter scored,” he said, yawning.

“What was it, a ‘breakaway?’” I said. I struggled to use hockey terms in earnest. “I know you said he’s quick.”

Owen didn’t respond.

“Well,” I said, “goodnight.”

“No, you,” he mumbled.

Soon I could hear his rhythmic breathing, which was only interrupted when the heater came on, the steam catching on a rut in the pipe and forging through. It was a loop of tedious sounds; I lost track of time, but tried not to check. I checked anyway; it was nearly 2:30. I was glad that I hadn’t told Owen about my promotion — he seemed not only tired but downtrodden — but I did want to tell someone. I pulled my laptop onto my chest and started typing out an e-mail to Jess, my friend from home. We had been very close, were still close, but still. Like Marlon, she was blunt; unlike Marlon, she had no tender side, no chirpy persona to put on when needed. She loved or she hated so-and-so, her paper on Petruchio was a travesty, and so, come to think of it, was Petruchio. When I started dating Owen, that had been a travesty, too — an imitation of love. He didn’t deserve me, he was a deadbeat and a jock. But soon they got along, and in fact, I spent more time with the two of them together than with either of them alone. It had become a system of checks and balances; Jess’s bluntness rectified my spurts of indecision about Owen, and Owen’s calm calmed her.

I squinted from the brightness of the screen. It turned out that Jess was online; she chatted me right away.

Jess: u up?

Nora: ha ha

Jess: why?

Nora: owen’s snoring

Jess: no he’s not

Nora: like, mouth-breathing

Jess: he does mouth-breathe

Jess told me that she was applying to graduate schools, mostly in Texas. She liked it at home and intended to stay. But the process was phony and tedious, and could I distract her, please? I told her about Marlon, who I’d feared was a “Lean In” type — ambitious to the point of exclusion — but who, I said, I was wrong about. I told her that I got pseudo-promotion, and she said that I was being falsely modest. I didn’t think that she was right, but the affirmation felt good.

Jess: did you celebrate?

Nora: oh,

Nora: i didn’t, like, tell owen

Nora: i just think it’d bum him out

Jess: hm

Jess: ya

Jess: men don’t like it when women are more successful than them

Jess: but since when does he care?

Jess: he’ll be happy, don’t you think?

I told her that things were different here, that bookstore jobs were competitive, and that although he wouldn’t admit it, all the rejection was wearing down Owen’s ego, was possibly depressing him.

Jess: and how do you feel?

Nora: oh, i mean, you know my thoughts on this

Jess: yeah…

Nora: that i’m able to afford rent here is a matter of good fortune. i see no reason why everyone’s success should be measured by the same metric, which happens to be monetary.

Jess: nora

Jess: i asked you how you feel

Nora: that is how i feel. i feel fine

Jess: which is why you’re sleeping so well!

Nora: i love you very much, but you are wrong

Jess: i love you too, and i am tired. goodbye~

After that, I slept easily. Even when I disagreed with Jess, talking with her was soothing.

The next morning, Owen was gone before I woke up. I didn’t think that he had another game, but we’d been missing each other lately, had lost track of each other’s schedules. I wrapped myself in my scarves and biked to work. Marlon was already at her desk, looking clean and awake. The wine glasses were still out, half-finished.

“Sorry I’m late,” I said.

Marlon waved a hand. She did want to talk with Dr. Christine Mayer and me, to pass the project off formally, she said. On the phone, Dr. Mayer spoke slowly, deliberately. It was as though everything she said originated from deep within her, and was, at that moment, being released into the world for the first time. I was dumbfounded; would I ever understand anything as well as she understood the psychological effects of displacement?

What I said was, “it’s a real pleasure, really.”

That afternoon, Marlon asked if I wanted to go with her to the B-list musician’s show later. He was known to interrupt his own songs with lengthy monologues — political spiels, mostly. She was considering him for a project after all, she said; she had found a decent ghost writer.

“Your boyfriend can come if you’d like,” she said. She was crossing something off on her desk calendar.

I considered this. It did seem like a chance for Owen to get out of our apartment, to meet someone — anyone — else, to put a pause on the job search. But I didn’t want Marlon to tell him about the raise. It seemed that either way, I’d be hurting him.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“No worries,” Marlon said. “Sam won’t be there either. It can just be us.”

“We should get there at 5ish,” she went on. “So we can leave early.”

I texted Owen that I would be home late again, and went back to mailing out contracts.

◆

The show was inside a temple that was converted into a concert space a couple of nights each week. Its walls were flanked with stained glass windows, but the effect was more art deco than place of worship, maybe because there was an acrylic chandelier hanging from the ceiling. Although the other bands on the lineup didn’t seem mellow, there were theatre-style seats that folded out, so that dancing or even standing would’ve been awkward. We were early — besides us, there was only a teenage couple cuddling near the front — so as soon as we found our seats, Marlon stood back up and asked if I wanted a drink. I nodded; yes, whatever she was having. While she was gone, I checked my phone, and saw that I had two missed calls from Owen. This was abnormal; we didn’t really call each other. He’d also texted: “noraaa.”

“Hey,” Marlon said, sitting back down, setting our wine cups on the floor. She noticed me pocketing my phone, must have noticed also a hint of alarm.

“Turn that off,” she said. “Whatever it is, it’s not worth it.”

Owen did get excited about small things sometimes — the Stanley Cup replica, for example, which he’d found at a stoop sale. I held down the power button.

“You don’t know that,” I said to Marlon. “What if it was Dr. Mayer? ‘Due to your new protege’s incompetence, I have decided to switch publishers. To stop writing altogether, actually. Death skull emoji.’”

“Dr. Mayer would never say that,” Marlon said. “She’s creative with her emoji use.”

“I guess I haven’t seen that side of her yet,” I said, laughing.

“In due time,” Marlon said.

People were filtering in, mostly people who looked younger than me, judging by their clothes. Doc Martens, chokers. Looks that’d been passé a few years ago.

“This is promising,” Marlon said. “A coffee table book crowd.”

We were sitting near the back, so I felt like an anthropologist, apart from the fray. But it wasn’t so clinical as that, because Marlon kept whispering in my ear, mostly jokes and wry critiques. Once, while the B-list musician was several minutes into a kindly worded rant on the ethics of meat-eating, she even tucked my hair behind my ear before whispering, “someone should tell him what combat boots are made of.” Her breath was cool on my face and smelled sweet. This wasn’t a sort of intimacy I was used to with a boss or even a friend; as close as Jess and I were, our connection wasn’t physical. A man in front of us turned around and shushed. He was wearing a jean-and-shearling coat, and he looked to be about Marlon’s age — ambiguously 40-something. Marlon didn’t seem disturbed by this, but emboldened; she kept whispering, but louder. I didn’t mind, and in fact I liked it. I felt like an initiate. I was glad, also, that Owen hadn’t come. He would’ve been uncomfortable — both with the singer’s bald sincerity and Marlon’s critique of it. He expressed himself straightforwardly, through actions, or descriptions of actions. He would have wanted to go home.

◆

After the show, Marlon and I went to a burger place she liked.

“All that talk about meat,” she said, sawing her patty in half. She scooted a plate towards me. As she started eating, her lipstick smeared the bun, which I thought was charming. I realized then how much I liked her.

“I’m glad you hired me,” I said. I knew I likely sounded false, but I meant it, so I didn’t mind.

“In your interview, you didn’t gawk at my name,” she said, swallowing. “It showed tact.”

“My mother loves ‘A Streetcar Named Desire,’” she went on. “The movie version. And she thought I’d be a boy. She ‘just knew.’ So it was Tennessee, Laurence or Marlon, after Brando. I think I’d have preferred Laurence. Laurie.”

Her parents sounded strange, and possibly self-interested. I pictured young Marlon, striving for normalcy, for approval. This explained a lot: the orderly desk, the orderly marriage. I told her I thought her name suited her, and that the reason, which I couldn’t pinpoint, had to do with phonics. Marlon agreed.

“So,” she said. “What’s going on with — Owen?”

I didn’t respond with specifics. Compared with her problems — finicky authors, a quirky first name, the wrong kind of wine — mine felt heavy, and awkward to discuss. Plus, we were having fun.

“Yes,” she said, switching topics apropos of nothing. She did this sometimes; “Yes, I am glad that I hired you. I think that we’ll be friends.”

◆

At home, Owen was lying on the bed again, flat on his back this time, staring up at the ceiling. He propped himself up on one elbow when I came in. The other arm, I could see, was in a cast. He waved, fake-happily.

“Oh my god,” I said. “What?”

“Yeah,” he said. “I called. A lot, actually.” He was smiling, as though he’d already accepted what had happened, and had moved on to wondering at life’s futilities.

“I turned my phone off,” I said.

“Right,” he said. “How was the concert?”

“Uh, no,” I said. “You first. Are you okay?”

Owen explained that he’d decided to join in on a pick-up game that morning. The other players were nice — this one guy had to’ve been like 6’8, but he was sweet, really — and besides you couldn’t check anyone, because there weren’t any boards. But the ice was rough, and he’d hit a knick. He should’ve known better than to try to catch himself with his hands, but luckily it was just the one wrist. He’d walked home after, figuring it was fine, but no. The swelling was bad, and he couldn’t ignore it.

“So my E.R. doctor was this woman from Russia,” he said. “No, the Soviet Union. She moved here in the 90s. America is better, she said. Except for the health care. If you’re healthy, it’s better. She went on and on. Her name was Yana. I think that’s beautiful. Yana.”

He gestured with his cast. We were sitting beside each other on the bed now, and I put my legs over his.

“Owen,” I said. “This is a big deal.”

“Yeah,” he said. “I know.”

In my head, I was doing the math, and it did seem feasible that we’d be okay, financially. He wouldn’t be picking up any more moving gigs for a while, but I was sure that he’d find other work soon. In the meantime, I’d keep biking to Marlon’s.

I exhaled, gathering myself.

“We’ll figure it out,” I said finally.

“Will we?” Owen said. “I feel like a leech. You’re already doing a lot. I just lay around and message people about packing tape. And rack up medical bills, apparently.”

“Yeah,” I said. “We will.”

“But how?” Owen said. “How will we figure it out?” He was looking right at me, and he wasn’t being falsely indignant. He really wanted to know.

“We just will,” I said. “We have to, so we will.”

“I don’t think it works like that.”

I didn’t want to talk about it anymore, was eager all of a sudden for levity. It felt like I hadn’t been alone with Owen for a long time. He carried a Sharpie around in his pocket, for his Post-It sketches; I reached for it and started doodling on his cast. Owen closed his eyes.

“You’re bad at drawing,” he said. “Now my cast’ll look like shit.”

“No I’m not,” I said.

“Draw Yana,” he said. “No, don’t tell me what you’re drawing. Let me guess.”

I sectioned off a portion of the cast so that Owen’s hockey players could sign and doodle on the rest. I tried in vain to draw a realistic-looking fire; Dr. Mayer’s book must’ve been on my mind.

“You’re drawing like a tree or something, aren’t you?” he said.

“No!”

Owen laughed.

“Tell me something,” he said. “About the concert.”

“I’m not sure,” I said. “Marlon just talked to me the whole time.”

“That’s annoying.”

“It wasn’t actually,” I said. “She’s funny.”

I scribbled over my drawing, blacking it out.

“It is Art,” I said.

Owen opened his eyes and frowned.

“So,” he said. “When do I get to meet her?”

◆

The next day, Marlon brought in bagels. It was, she said, a minor celebration, but a celebration nevertheless. Dr. Mayer would be visiting us next week, would be coming over for dinner. Sam would be there too, she said; he had cleared his schedule. Her voice went soft when she said this, and I could tell that she was already anticipating it — the prospect of entertaining.

“Please bring Owen,” she said. “More is more.”

I considered this; if Marlon and I were going to be whatever we were — co-workers who were also friends — she was going to meet Owen eventually. I didn’t think that they would like each other, but that wouldn’t be so bad.

“Yes,” I said. “I’m sure he’ll come. But can you not mention the raise? He’s dealing with a lot, and, I don’t know, it feels like bragging.”

Marlon nodded.

“I get it,” she said.

◆

Owen kept skating, even with the cast. He couldn’t break his wrist twice, he said; it was like double jeopardy.

“Interesting logic,” I said. But we were already on our way to the rink. It had become his pastime and the center of his social life, so of course he wouldn’t stop. And I liked going too, liked being aware of Owen’s presence nearby while I read on a park bench.

It was crowded that day and unseasonably warm. There was a father skating backwards, pulling his daughter along; there were teenagers skating in t-shirts. There was an older man in a tweed jacket skating alone, very slowly, with his hands in his pockets. It was as though he was taking a walk. I knew Owen would mention him afterwards; this was the kind of character who interested him. We’d spend the afternoon guessing at his story. Mourning widower, or happily alone? The rink was so packed that I’d lose track of Owen, but his red cast would flash by and I’d find him again. It was exciting and comforting in turn, the loss and the rediscovery. I tried to relate this to what Marlon had told me about her relationship with Sam, but I knew I was straining. I turned back to my book, and when I looked up again, I could spot it right away, that red cast.

◆

Owen and I walked to Marlon’s dinner party. The snow that had piled up on the street corners was melting into slush, and we were both wearing our nice shoes, so we circled widely around each intersection, and wound up being twenty minutes late. Owen had been nervous to begin with — he kept rolling up his shirtsleeve, then unrolling it, so that it wrinkled — and now I was nervous, too. I wanted to make a good impression on Dr. Mayer, and I wanted Marlon and Owen to get along at least amicably.

When we got there, Marlon buzzed us up, and when she greeted us her face fell.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I feel like we’ve just been on an expedition. Google Maps should account for slush delays.”

“Are you late?” she said. “I didn’t realize.”

“I’m Owen,” Owen said.

“Owen,” Marlon said. She gave him a side-hug. “You look like that actor.”

She seemed harried; she didn’t elaborate. She ushered us into her living room, where she’d set up a table with candles and chargers, and what looked like bowls of small, pickled vegetables. A woman in a tunic and a decorative scarf was examining some kind of radish, absently. When she saw us, she stood up.

“You’re Nora,” she said happily. “We’re waiting on Sam.”

Marlon was clanking around in the kitchen. From the sound of it, she was moving pots and plates back, forth, back again.

“Need help?” Owen called out.

She didn’t respond, but he joined her in the kitchen anyway. Dr. Mayer and I sat down and poked at the vegetables with toothpicks that Marlon had set out in a tiny canister. She didn’t ask me many questions about myself, which was a surprise and a relief. Instead, she told me that she was anticipating her book’s release; a peer of hers was coming out with a title that would seem similar to the lay-reader.

“They’re very different subjects, of course,” she explained.

Marlon emerged then from the kitchen, with oven mitts on both hands. She was carrying a pan with a roast chicken, and Owen trailed behind her; it seemed he’d been enlisted to carry out the rest, in spite of his cast. I stood to help him, but he shooed me off.

“I’d say let’s eat” Marlon said. “But I’ve got to make a call.”

She went to her office, and we tried to make small talk that would muffle her voice, which was not curt as usual, but swollen and billowy.

“Once again,” I heard her say, and “you’ve mentioned that already.”

“So Owen,” Dr. Mayer said, clearing her throat. “What do you do?”

“Oh,” he said, fiddling with his shirtsleeve. “I’m not sure yet.”

“You’re very young,” Dr. Mayer said, nodding.

“We met at a bookstore,” I said. “We were both working there.”

“How nice,” Dr. Mayer said. “Like a scene from a movie.”

“It was a long time ago,” Owen said. He shot me a look.

Marlon came out from her office and clapped her hands together. She looked like an uninspired cheerleader. But she really was trying.

“Okay,” she said. “Just us, then.”

While Marlon carved the chicken, Dr. Mayer told us about the research she’d been unable to include in her book. There were evacuees who had inadvertently formed their own communities, mostly in campgrounds further north, near Yosemite. That they had all been displaced wound up bonding them; in some cases, the residents were happier than they had been before. This was especially true for those who’d been dealing with bad traffic, bad schools, and other governmental failings.

“Nora and I know about displacement,” Owen said. “We moved here last fall from the South. I thought the cold would bug me, but actually it’s the noise? When it screeches, the train sounds like trees falling down. Like, breaking off into splinters. And then falling down.”

“We weren’t displaced,” I said. “We chose to move here.”

“That depends on what you consider a choice,” Owen said calmly.

I knew that he was trying to invoke Sartre, which was something he did at parties, and never at home. I found this no less embarrassing than if he’d made a personal jab.

“This isn’t philosophy class,” I said, and Owen blushed.

“He’s right in a way,” Dr. Mayer said. “Some people evacuate hastily, without orders. Others stay even when conditions are lethal. There are of course socioeconomic considerations. But it’s also correlated with attachment type.”

“This is why we signed her on,” Marlon said to no one.

“And,” Marlon went on, “when I reached out, she didn’t say anything about my name, which I thought was tactful.”

“It’s a lovely name,” Dr. Mayer said. She turned to Marlon. “Resolute, like the fish.”

“My grandfather was a fisherman,” Marlon said. “For his livelihood, and also for sport. He died young, so he was my namesake. It was either Marlon or Char. I think I would’ve preferred Char. Like Char-lotte.”

Everyone laughed, and moved on. I stared at my drink, which was watery now. Owen and Dr. Mayer were getting along well, were talking about hasty evacuations, about how fire has not one smell but many, also about choice as a philosophical concept, about Sartre, and about his cast, which was covered now in autographs from his team. I tried at several points to re-enter their conversation, but Marlon was talking with me about dinner, and, in spite of herself, about Sam, who she said wouldn’t have liked the chicken anyway.

◆

“You want to know something weird?” I said.

Owen and I were walking back home.

“Sure,” he said.

“Marlon lied about her name.”

“What’s her name?” he said.

“Her name’s Marlon,” I said. “But she told me she was named after Marlon Brando.”

“Oh,” Owen said, losing interest. “Maybe both things are true.”

“I don’t think so. The way she told the story was the same, but the details were all changed around.”

“Listen, Nora,” Owen said. “Tonight kind of sucked. I can tell you’re embarrassed of me.”

“What,” I said. “No.”

“I’m not stupid,” he said.

“No one thinks you’re stupid,” I said. “You’re the only person who thinks that.”

“Gosh,” Owen said. “I wonder why.”

I started to think of excuses for how I’d acted, but he was right.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

Owen ran and jumped over a slushy corner, and I did the same. We walked ahead for a while without talking.

“I know you got a promotion,” he said finally. He was looking straight ahead. “Jess told me last week.”

I hadn’t expected this, but maybe I should have.

“That’s true,” I said. “I did get a promotion.”

“That’s awesome,” Owen said. “Seriously.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” he said, after a time.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I didn’t feel like I could.”

“Why?” Owen said. “Because I can’t find a job?”

“Well, yeah,” I said.

Owen looked taken aback.

“Man,” he said. “Are you sure you don’t think I’m stupid? Because it kind of seems like you do. Or maybe you just feel sorry for me. Like, ambient pity.”

“I don’t pity you,” I said. “I just don’t think we need to tell each other everything.”

“Okay,” Owen said, “But we moved here for this. I moved here, with you, for this. It’s a pretty big deal. This isn’t, like, what’s for dinner.”

“Marlon and Sam don’t tell each other everything,” I said. “Even big things.”

“Sure,” Owen said. “Seems like a model relationship.”

“That’s not cool,” I said. “That’s actually a really uncool thing to say.”

I was conscious of sounding irritable. Walking so far through the slush was uncomfortable.

“I’m just ready to go home,” Owen said.

“Me too,” I said. “My toes are wet. Not cold, just — wet.”

“Nora,” he said. “I mean home-home.”

We were at a crosswalk. I looked at Owen. “We just got here,” I said.

“Yeah, and already you’re never around. You’re always working or ‘out.’ I’m just in the way.”

“You’re not in the way,” I said.

“I wouldn’t ask you to come with me,” Owen said. “I wouldn’t ask you to do that.”

I tried to imagine our studio without Owen in it. Materially, it would be the same. We had no untangling to do, no divvying up of furniture, of books even, because we had packed so few of them. This seemed somehow worse; the only thing that would be missing was Owen, and, faced so plainly, this fact was almost intolerable.

We’d stopped walking, and were sitting on somebody’s stoop now. I understood why Owen would want to leave, also why he assumed that I’d stay. He was right; of course I would. Our life here — my life here, now — had a provisional quality that suited me, a quality that, perhaps foolishly, I wanted to sustain.

“Maybe I’ll come back later on,” I said. “Or you can come back here.”

I was grasping at platitudes, anything to soften what was happening.

“Absolutely,” Owen said.

We both knew this was too affirmative to be true, to have even a note of truth in it. We sat there for a while, not talking. Eventually a woman with a little dog came out of the building and squeezed past us.

“Everything all right here?” she said.

“Yes,” Owen said, and we figured it was time to head on.

◆

In the summertime, Marlon’s office felt less like a haven. The studio was a more peaceful place without the radiator’s hammering, and I’d finally bought a bed frame. But the light at Marlon’s was nice, and it stayed light so late that I often worked until eight or nine, or else we went out to dinner together at the burger place she liked, which had become our celebratory go-to. Like before, there was often something to celebrate. Today, there was no air of pretense about it; final copies of Dr. Mayer’s book had arrived. Marlon had placed one on her floating shelf, and had handed one to me, to keep. I was surprised to find that my name had made it into the acknowledgements. Seeing it there in print when the work I’d contributed was minimal had a dissociative effect. Who? I thought. Still, I carried my copy with me in my backpack, and kept flipping through it over dinner.

“Don’t rest on your laurels,” Marlon said, chewing.

I was working with her on the B-list musician’s book, which needed a heavier editorial hand.

“I thought we were celebrating,” I said, and I felt my phone buzz. I’d e-mailed Jess a picture of the book, and figured that she’d written back.

“I’m checking it,” I said. “Sorry.”

“In that case,” Marlon said, and she excused herself.

It wasn’t a message from Jess, but from Owen. My throat tightened. When he left — he’d arranged to take several busses back home, and I’d helped him put together the fare — we’d decided not to talk for a while. This was the first that I’d heard from him. The subject line of the e-mail was “tell me something.”

I considered this; over the last several months, I’d wanted to tell Owen so much. How once on the train it seemed that everyone in the car was sick, so the mood was convivial, a chorus of congestion; how the ceiling of our closet caved in, which was practically a non-issue, and aesthetically an interesting problem — what sort of fabric could I buy to cover the damage, velvet or some kind of nylon?; how when it rained, nobody knew what to do, like the apocalypse had finally come; how in June, the garden had roses. I could tell these things to Marlon, but she would’ve been bored by all that, would’ve asked me, “so what?” and moved on to something less habitual — less juvenile, in her view — something new and immediate and therefore more vital. I looked at her plate. Her burger was smeared with lipstick again. It wasn’t only charming but affecting to me, no less so than any of what I’d wanted to tell Owen. I looked at my phone again and without thinking I deleted his e-mail. It felt like the wrong thing to do, but undoable, I thought. Still, I sat there with the decision, and let it gain heft. It is easy to live this way, I’ve learned. To busy yourself, to get lost in time, to make choices on impulse, to build up reasons later, to really believe in those reasons. The longer I sat there, the farther away Owen felt. I put my phone away and waited for Marlon to come back.