The wilderness, in western Montana. Miles and miles of pines. Night-time. A stony beach. A river. On the beach, a fire, with bright orange flames. Into the night sky, black rafts of smoke. A mother, two sons. Just them, in this wilderness.

The mother, Marta, fried their dinner in a skillet. “Not so bad, is it, boys?” she said once the food was gone. Rafael, who was eight, said it wasn’t so bad, but teenaged Liam didn’t answer. The fire gave off a wavy kind of heat, casting the beach around them in a mixture of winking light and shadows. Listening to the wind and smelling the fried beans, they sat there, not talking. When something like a train whistled in the distance, Rafael said it was a wolf.

“I don’t think that was wolf, Raff,” Liam said, before spitting on the stones at his feet. “That didn’t sound anything like a wolf.”

Rafael turned to his mother. “You ever heard a wolf howl, Mom?”

Marta threw her head back and did her best impersonation of the packs along the Salmon. Ah-wooooo! Ah-ah-ah-wooooo! When she’d finished, Liam was staring at her.

“Look at yourself,” he said. “You’re a clown.”

Marta fanned smoke away. “Does it matter? Who’s around?” These kinds of jabs were becoming more common since they’d learned just how bad things were with their father. She was learning how to deal with them.

Rafael leaned back and let out a howl of his own, a high shrill ear-splitter that sounded more frightened stray dog than wolf. Marta patted him on the back. “You do a mean wolf. Your brother couldn’t touch that.”

Liam picked up a stick and snapped it in half.

“Oh, come on! Howl, Liam.”

Liam threw the sticks into the trees.

“Howl! How-el! How-el! How-el!” Marta slapped Rafael on the knees, urging him to join in. He did. “How-el! How-el! How-el!”

“I think I’m done,” said Liam, before he went to the tent and shut himself inside.

* * *

They had come into the Bob Marshall—the Bob, locals called it—from their home in Billings, for the first time this year, repeating an annual trip. This was the first time without their father. Tom was back home, ostensibly working on his metal-work. He had macular degeneration now and his doctor had advised no more expeditions into the wild. Marta, a former river guide, couldn’t fathom the year without the excursion. So here they were, even though it wasn’t quite summer yet and every now and then they’d find pockets of snow.

Hiking the next day was arduous, the incline steep enough that Rafael kept losing his balance. “You okay?” Marta asked as they trekked along, reaching out to steady him.

“Yeah, I’m fine,” he assured her.

Meanwhile Liam blazed ahead, smacking at the weeds on the sides of the trail with a long stick. He’d been getting so far ahead that sometimes Marta was having trouble seeing him. “Hey, Liam!” she called out. “Stay where I can see you!” “Yeah!” he answered without looking back.

A little past noon, when the sun was in the middle of the sky, they sat down to eat. They got out their sandwiches and dropped into silence. Liam plowed through his salami and cheddar in less than a minute. Perched on a boulder in the shade of a Ponderosa, Rafael slowly made his way through a package of raisins, gumming each dried fruit as if trying to suck out its last drops of juice. He was so different from his older brother. Marta and Tom had adopted Rafael from Honduras when he was not yet one. Though bald and tiny when they first got him, he now had a full head of dark hair, large brown eyes, a clever red mouth. The difference of six years between him and his brother surely affected their relationship, but it wasn’t as though they’d never gotten along. That had only come about more recently. When Rafael was little, Liam would read to him books Marta had bought from the university bookstore: The Ancient Mayans: A History in Pictures; The Golden Pyramids, Legends of the Maya; The People of the Forest. All of these books about the people from the country in which he was born. In Honduras, the indigenous peoples were discriminated against, in the lowest caste in terms of race, beneath those who had mixed with the conquerors and the conquerors themselves. Raff should know from whence he came, they thought.

“I’m still hungry, Mom,” Rafael said, looking at her.

Marta rummaged through her pack. “Carrot sticks?” She handed him the plump baggie. He began crunching on the snack, gazing off at the surrounding pines.

Back home in Billings, Rafael and Liam would go on bike rides together, down the mountain and across the street to Loebeck’s Farm. Was the change inevitable—the growing distance between them—to be expected, Liam being a teenager? Or was there some distance between them because of what was happening with Tom? It seemed the potential blindness of their father had put strain on them, the way it was putting a strain between her and Tom. Marta brushed crumbs off her knees. She stood up. “All right, boys. Let’s keep going.”

They walked down the trail and, after about an hour, saw an eagle, shooting silent with its wings spread. Liam picked up a rock and threw it at a tree. The rock left a harsh yellow gash in the Ponderosa’s bark. Before nightfall—night beginning to drop around them—they found a strip of sand and decided to set up camp. To their left was a border of aspen; across the river, pines formed a serrated black wall. Marta led a search for tracks. Headed in the opposite direction, Liam stalked off into the woods to pee. On the edge of the aspen thicket, Marta found prints that no doubt belonged to a grizzly. In the mud, the print had five distinct claw marks. “You see how deep this track is here, Raff?” said Marta. Her son nodded. “You can estimate the weight of the bear by the depth.” She placed her knuckle in the mud, feeling its cold, its dampness. “About six-hundred pounds, this guy.”

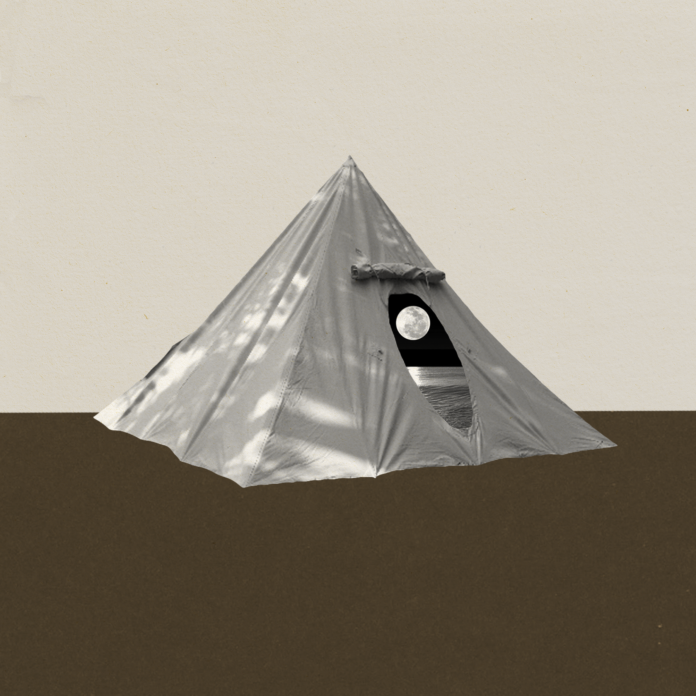

They walked to the riverbank, which was stony, as though covered in large gray eggs. They pulled the tent out and carried it to a softer sandy section. It looked a pale green in the dim light. “You interested in howling yet?” Marta asked Liam. He shook his head. “You having any fun? I want you to be having fun, Liam.” He looked at her very squarely.

“No.”

She built the fire, cooked chicken breasts that had already been seared once through. The moon came out. After taking turns using the bathroom in the woods, they got into their sleeping bags. The air in the tent was thick and buttery and still. Under the noise of the river, Marta could hear her sons’ breathing, rhythmic and deep. She turned onto her side. The smell in the tent was waxy and had tones of a masculine funk she couldn’t help connecting to her teenaged son. The smell seemed to cling to her face. Through the angular canvas roof, she could see the surprising lightness of the sky.

When Liam had first started to become as handsome as he was now, with those long muscular legs, that angular face, that curled dark hair, she had felt genuine fear being in his presence. He reminded her of the boys she’d at once hated and admired and longed for in high school, but who had called her “dyke” or “archaeologist” because she wore hiking boots with orange laces, neatly pleated khakis. One day one of those boys called her over to the flag pole—“Yo, Marty! Marty, over here! What is this? What kind of snake?”—insisting he needed help identifying a snake. Behind the school’s low creekstone wall she found a black leather belt dropped in the dirt. “What kind of snake is that, Marty? What kind of snake?” “Don’t let it bite you, Marty!” another boy said. “It’s poisonous!” The belt was spattered with beige dust. Its buckle formed a silver rectangle. Marta had the instinct to pick it up and whip it at the boys, maybe even lash them across their faces with it, but quickly this instinct collapsed, and consumed with humiliation and a baffling shame she ran away.

Liam had started wearing belts like that. She’d had to take him to Macy’s for back-to-school shopping. Smelling all the braided leather in that enormous department store, Marta had felt sick. Her son rustled beside her. The tent was big—twelve by twelve—but she could almost feel him breathing. The scent from Liam’s teeth, brushed in haste while using distilled water in a blue tin cup from home, was of spearmint. Liam rustled in his sleeping bag. His breathing sounded jagged. Marta stared at the tent ceiling.

* * *

In the morning, the sky shone gray, save for a few stray patches of a silver light. The air smelled of moss and damp wood, as though it had rained, or was about to. A small airplane could be heard groaning through the clouds.

Marta led the way down the trail. Rafael reached up and took her hand. They came to a slope leaning down into the river, into the Bitterroot, and they sat here, on some rocks, looking at the water. Liam ate a sandwich and tossed his crusts into the current.

“I want to hear a story,” said Rafael, so Marta told them about the time she and their father had been hiking in this wilderness, when they had come across a black mountain lion. At first they thought it was a lion that had rolled in the ashes of the summer’s forest fires, but then, years later, they saw it again, and it was much bigger, with shoulders like boulders, and it had that same dark coat. They realized it was a true black lion. “An anomaly,” she informed them.

“Wow.” Rafael popped a grape into his mouth.

It was likely Tom would be blind by sixty. He’d been a furniture-maker all his life, was regionally known for his Quaker-style cabinetry, his elegant teak tables and arrowback dining chairs. Tom had once lived in Newfoundland, and if you looked closely you could see that he placed in each of his pieces a bit of Newfoundland’s bare, open green spaces, its stony coasts, its wind. Now barbed wire was what he worked with because it was more tactile; it demanded more from his hands than his eyes. But it was possible he wasn’t working on, making progress on his chandeliers today, but wasting time in the study, which was what he did when he was gloomy. Aimless web-surfing had become a kind of vector for his despair.

“Let’s keep hiking,” said Liam.

They made their way onto the trail and after about three miles, they came to a tree fallen across the Bitterroot. It was a log, really, a felled, branchless pine. Thirty or forty feet long, it stretched from bank to bank, the water beneath it a grade-five rapid, rock-ridden and fast. Seeing the log, Liam pushed up his sleeves. “Don’t think about it, Liam,” Marta warned him.

“It’s tempting,” he responded.

“Don’t!” said Rafael.

Marta walked a few yards and found, behind a stand of bluebunch wheatgrass, a pile of what resembled that dreadful cereal both her boys liked so much, Cocoa Puffs. She reached down and picked up one of the pellets. Mule deer scat. Cold, so it had been a while. She squeezed a single pellet and felt it crumble.

“Mom!” screamed Rafael.

Turning, she could immediately see Liam receding through the river’s mist. He moved across the log, arms at his sides, tilting. He got farther and farther away. But, he made it, and with a jump he landed on the opposite bank. The log between them was gnarled, knobbed in places where once-healthy branches had broken. Patched with spots of gray bark, it looked weak. Across the river, Liam lifted one leg and then the other. He turned and showed her his butt. He shook it side to side, wiggling in his basketball shorts.

Unbelievably, Marta felt tears sting her eyes. Something about the sight of him over there, his deliberate dismissal of her, made her vertiginous with anger. His jauntiness, his cockiness. . . She tugged Rafael’s hand. “Come on,” she said. “Follow me.”

“What? Mom? Where are we going?”

She was moving south along the river and tugging Rafael along with her.

“Mom?” said Rafael. “Mom! Mom! We can’t leave him!”

At another moment, she would agree with him; and in many respects he was right. It was too dangerous out here for Liam to be left alone. The wolves were not around, and they didn’t really harm people anyway, keeping to livestock. But the bears, the lions, they posed a real threat, even though it wasn’t yet the hunting hour. It was the middle of the day, but still, animals would be out. Of course, there was the river, and the possibility that he’d try to cross it by walking, wading, or swimming, or even trying to cross the same log on his way back…. But he’d made this decision, and he should have thought better of it.

This was her way of picking up the belt, she knew. The boys had left that leather belt in the dirt for her. She hadn’t picked it up. Now she was.

“Mom!” Rafael jumped, horrified.

“Don’t pull away from me, Raff!” Marta shouted. She jerked him closer and trudged on.

They traveled a mile. Though both of them were breathing heavily, they weren’t stopping; she wasn’t stopping. In addition, of course, Liam didn’t have any of the packs. The insulated cooler pack, the pack containing their night clothes, the pack with the bug-spray, the bear-mace, the sun creams: she, his mother, had all of these. It was a delicious feeling, knowing her power, and knowing that her son would come to recognize it. Marta continued pulling Rafael along as they headed down the Bitterroot.

Pines passed; they hiked in silence. Every now and then Rafael let out a whimper. Marta disregarded his noises. For twenty-three years she had been a guide on the Salmon, in Idaho, leading multi-week trips for the outfitter One Thousand and One Waves. She wore a white helmet while everyone else wore yellow. A number of her charges had been vegetarians, and, for fun, Marta and her co-guide, Patrizio, would monitor these so-called veg heads. On the eleventh day of an expedition—the morning they broke out a slab of bacon and fried it—the alleged herbivores devoured the meat as though they’d been starving. Circumstanciavores, Marta said was a better term for them. That’s what we all were, really. Under the right circumstances, or the wrong ones, depending how you looked at it, we—human beings—could do anything. We are circumstanciavores.

Marta stepped over a high stone. Among her favorite river memories was meeting Tom. He stepped into her raft one day with friends. For years afterward they would joke how he’d started as one of her charges, a paying customer. “I can still see his bright, smiling face,” Marta said when telling the story of their meeting. “Of course by the end he was soaked and miserable. I wasn’t willing to give him a ride he’d forget.” But it wasn’t Tom who made her give up the river. No, Tom told her to keep at it, he knew it made her happy, made her feel necessary, important. It was Liam. When she became pregnant with him, Marta swelled, became large, yet felt delicate, fragile as a flower made of glass (she had seen those at Harvard, once). She was aware of her body and her presence within it in ways she never had been before. Marta Kramer-Plaksin could no longer risk the rapids. Set her eyes on desolate, undulating canyon walls, feeling one with their solitude. She was to be a mother, now. She sacrificed the river for her son.

Marta looked over her shoulder at the water. She wondered what Liam was doing, upriver. At home, he would be in the basement, playing video games. One of his friends would be over. As the hours passed, they would traipse into the kitchen and grab something to eat. Leave the discarded remnants of a frozen pizza on the countertop, a mess of tomato sauce and black olives. Marta drew a breath. Each step she took, she wondered if he felt that, if he felt her footfall on the pine needles, on the moss, if he felt a little stab of fear, of vulnerability. She hated, she had to admit, his usual imperviousness, which, to her, was so distinctly male. Across this country, right now, how many other young men felt that same imperviousness? Like they couldn’t be touched. Like nothing they did could bring them harm. That was what was wrong with the world.

A few rain drops fell through the pines. She looked up at the shapes of the trees—like green church spires. She couldn’t say how long they had hiked for, but when she looked down she noticed Rafael was crying. “We have to go back,” he said. “We can’t just leave him!” Marta felt some lightness coming into her, some slight yet perceptible interior shift. She looked beyond Raff, to the Bitterroot. The river here was smoother, deeper. Bubbles whirled on the surface like minute white skulls. “You can swim, if you want to,” she told him. “You can take your shirt off, and get in.”

“I don’t want to. I want to go back.”

“He must be scared. But he’ll be fine.” She waited. He didn’t move. “If you swim here, he’ll catch up with us. He saw which direction we went.”

On the water stretched long, dark pine shadows. Rafael looked at the water.

“I want you to swim, Raff.”

“I don’t want anything to happen to him.”

He probably said this about Liam, he didn’t want anything to happen to his brother, but for some reason she thought he might be referring to Tom. “He is going to need our help,” she said. Maybe she was saying it to herself. “But he’ll still be himself. He’ll still be your father.”

Slowly, Rafael pulled his shirt off. “Will you get in with me?”

Marta looked at the water, the cold brown promise of it. She knew what release it could give—that evaporation. The river erases. But there were certain things she couldn’t do anymore. As a mother, she had certain limitations. And she did have to honor them. She couldn’t let everything go, and bask as she once had. Yes, she could get in, she could swim. But she would swim as a mother watching over her son, protecting him. If she let go and gave herself over to the river, it would be so hard to trudge back onto land.

“You go ahead,” she told Rafael, and he handed her his shirt. He went and got into the water, while she stood on the bank, half-watching him—his little head blackened by the water—half-watching for Liam.