The drain fly doesn’t move, even when she slaps the wall. It’s alone. To the naked eye he could be a fleck of filth, or a chip in the paint. But Anita knows the tell-tale clover shape and the thing’s unwillingness to move from a threat. They don’t fear death. They don’t know if they’re animal or mineral.

It’s no use trying to deal with one herself. Management had exterminators in, and they were gone from the lobby for a week or two but came back at the start of May. Then management swapped out the hanging plants for standing ones. It was a strategy that all parties seemed extremely satisfied with. Anita watched one night as men with very short hair and pads of flesh coming from under their shirts hauled a cactus from a red van into the lobby. Why would it matter what plants might be attracting the bugs? she’d thought at the time. The clue is in the name. Drains.

She leaves it on the wall. Room 105 is next: a single. No one answers when she knocks, so she knocks again. Her hand hovers over the floor’s master-key, tied to her belt, the belt tied to her apron, too heavy for her frame, like the lead ones dentists keep for X-rays. She says “Good morning” as loud as she can without it becoming a shout. She follows it with something that’s not a word in any language, simply a sound. She says this directly into the door, her nose almost touching it, then knocks one more time. She lets herself in.

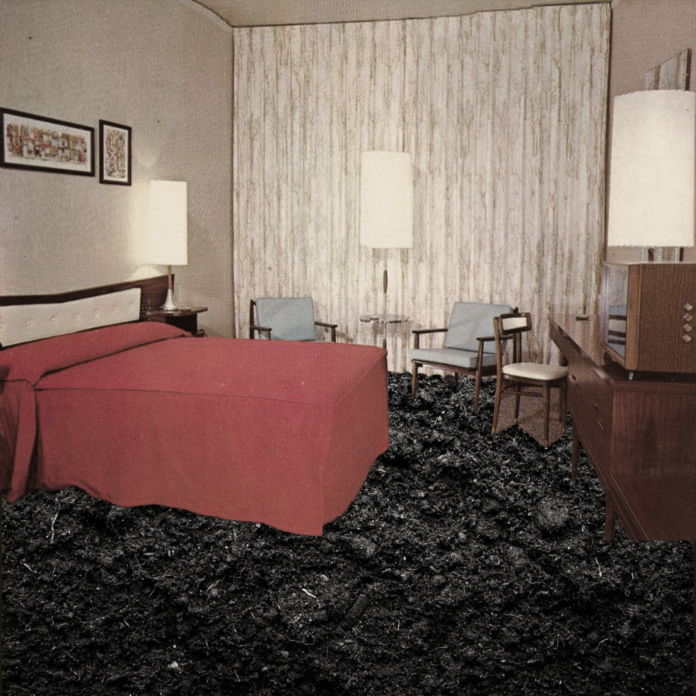

Once inside she finds a full, open suitcase and an untouched bed. The laminated Soilage Charge £150 sign has been moved, just an inch. There it is: the knot in her chest. She turns her gaze to the bathroom door.

“Excuse me?” Anita raps her knuckles on frosted glass. She hopes she’s wrong. She never is. “Excuse me, ma’am?”

She hears the first signs of movement. Mumbling. The squeak of flesh on porcelain, or whatever the bathtubs are made of.

“Don’t get up, I’ll come back!” Anita shouts.

She doesn’t mean it, of course. It’s almost eleven thirty. Still, she goes through the motions of heading to the door, gathering the cart. Maybe she can avoid contact this time; hide out in room 106 for a moment, maybe even sit and flick through the five channels. Maybe there will be a news story on about nothing terrible, something benign. But Anita is too clumsy for this vanishing act. There are cleaners at the hotel that are better versed in it. Not her. She’s halfway out the door when she hears the woman in the bathroom start to speak.

“Sorry.”

The voice is heavy with sleep. Anita stops.

“I..it’s a funny story…” the voice continues. But she trails off.

Who is it for? Anita frequently wonders this. They always want to explain. Sometimes when this happens, Anita pretends to speak less English than she does, smiling dopily, nodding on an awkward diagonal. There is a lightness in this, a freedom. But it’s too late for that now. The woman has begun speaking full sentences. She’s saying something about her back, her lower back.

“I’ll give you a few minutes,” Anita says, and she turns quickly, pushes her weight onto the cart, and lets the door click shut behind her.

No. It’s not true that all of the women try to explain. One woman didn’t. Last year sometime.

“You must get this all the fucking time,” the woman had said to Anita, looking straight into her eyes, fierce, pushing hair out of her own face. Her skin shone with a certain type of grease: travel grease, insomnia grease. There’d been a red patch on her face, a mark from the tub’s hard surface. “Can you have a word with your manager about that fucking sign, please?”

The woman’s eyes had become wet. Anita froze. She tried it then: looking simple. It hadn’t worked.

“Can you have a word with your manager about that fucking sign?” The woman said at the same volume, identical to the first time. She could have had a pull-string on her back like a doll.

Anita can’t believe she’d forgotten about this. She rests her forehead on the wall in the hallway. Her eyelids are heavy, eyes dry. She considers leaving an extra chocolate on the pillow for the woman. It might be kind. But it would mean re-entering, re-approaching, getting back into the woman’s path, and Anita couldn’t help but feel something superstitious about that. A curse, or a collision. She thinks about leaving the chocolate just outside the door, where guests leave their room-service trays. Someone will step on it. The woman in the room, or the next guest. Anita will be the one who’ll have to clean it up, on hands and knees. She drops it there anyway. She knocks on the next door.

On her way out, she overhears Danny telling a family of four how to get the bus to town. He tells them it’s about a twenty-minute journey, and to be sure to get the 46, not the X46. If they get the X46 they’ll end up in Altrincham, or the hospital staff car park.

◆

The glow comes out the ground-floor window, her window, small spots of the black bins light up electric blue. She thinks of jellyfish. She’s never seen a jellyfish. She doesn’t plan to.

Kir left the television on downstairs. He hates the quiet. Her sisters had decided that he was old enough to fend for himself at home, and they’d issued the decision to her like bold new legislation made after a summit. It’s hard to tell how he’s been coping. Eleven still seems young to Anita, young to be fending for yourself for entire weeknights. She’ll pretend to believe that leaving the TV on was an accident.

Once inside, she drops onto the sofa and peels off her socks. She can’t quite untense the muscle connecting her shoulder to her ear. Her sisters say that she needs to see a muscle doctor – that’s how they put it. Anita asks when she’d have time; her sisters find something else to talk about. A shock of pain makes her slap the sofa and clutch her neck. She breathes once, twice, and lets it pass. Sometimes when this happens she makes a very tight bun at the base of her neck and lies down flat, the weight of her neck pushing into her hair, a stone into her brainstem, and everything relaxes, just for a moment. Sometimes she can sleep like that. She hasn’t been sleeping lately. When she does, she dreams in English. The English of this part of the world, and also the English where the girls fly in from.

◆

The exterminators left a contraption in the stockroom, something halfway between an apiary’s grate and a dog’s water bowl. Some of the flies have drowned and transformed into an opaque mash. A patch of them remain living, filling the air, hovering an arm’s reach from Anita’s face. She reties her apron behind her back and refastens her pager, the one cleaners are issued, the one that doesn’t beep, but quacks – a duck’s quack – on the hour, every hour. She can’t imagine who chose that sound. The duck. Who loves ducks that much? Who loves ducks at all?

She knows that one day she’ll be asked to remove the dead drain flies. She knows this, even though it can’t possibly be her responsibility to do so. They have plumbers. They have the exterminators that they could call back, probably for a small fee. Still, she knows that it will be her.

“Your mum’s staying here then?”

Through the service door at the far end of the stock room, she can make out Danny’s tones. His accent is more extreme than most, all tongue, all echo.

“Um…” The voice is small. Anita can’t guess how old.

“S’alright, I’m sure she gave you a confirmation email in her name to check in with.”

He’s speaking too loud. He’s still getting the hang of this, Anita thinks. He’s trying to help, but he’s speaking too loud.

“Is that correct?”

“Um…”

“Or maybe she’s coming to meet you later?”

Anita shuffles through the door, and after that the door to the back office, with the buzzing lights and the rot-yellow carpets and the Soviet smell. The room with the two-way mirror, a lingering reminder of a time when the hotel could afford security. It’s empty; she leans on the wall and squints at the scene.

The girl is scratching her arm. She could be any age, fourteen or twenty-two. Her hair is dyed a cheap-looking jet black, but dusty blonde roots leak from her scalp. Finally, she answers: “Yeah, yes, she’s comin’ to meet me later.”

“That’s great,” says Danny. “I’ll just make a note that she’ll be paying by card when she arrives.”

“Um –”

Anita presses a palm to the glass. She prays that her pager doesn’t go off.

“Unless you’ve got cash on you now?” He smiles. “That’d make my job dead easy!”

Good, Anita thinks. He is good at this.

The girl drops a black backpack onto the floor. The plastic clasps make a sound like Christmas when they hit the tiles. “I have cash on me now.”

“Fantastic.”

Anita leans back. He’s done well, she thinks. Not been too obvious. Not so much so that she could tell her brothers he’d been encouraging her, were they brothers to show up, to cause trouble, to ask questions. They always have brothers, these girls.

From the bus stop Anita can see the woman with the leaflets standing outside the Warhammer shop. Her lips are moving but she can’t make out the words. Something in her shifts each time Anita looks away and comes back: now the woman seems melancholy, now she seems to be singing, now she looks to be in her mid-thirties, now her late-fifties. She shifts her weight back and forth, left foot to right. She shifts like that, maybe because she’s cold, but it’s not cold today. At least not where Anita’s standing. It’s half past eight and there’s still a shard of light on the horizon.

Tonight Anita makes the bun, plaited into a stern silvering knot, and ties it off with a hairband from the bottom of her sister’s bag. With one hand she places it in the shallow zone just below her skull, where the tendon becomes bone. She gently lowers herself onto the floor with the other hand, onto the laminate that’s mostly covered by gummy rugs that the flat came furnished with. She positions the bun one more time underneath the weight of her head, and begs her shoulders to slide away from her jaw. They listen with middling obedience. She lets her spine imprint on the floor. Her legs pull from her body before going limp. She pushes the bun into her neck, her neck onto the bun. The release is like laughing gas. The pressure makes her turn liquid. She falls asleep almost instantly, and wakes to Kir prodding her thigh with the tip of his toe. He’s in his blue pyjamas, and Anita thinks instantly of porcelain; red spots on pale skin, of the curve of a bathtub. She knows that her first movement will be agony. She hasn’t slept this soundly in years.

It’s past 8 am. She’ll be at least thirty minutes late. Maybe Lukas can cover for her. Kir is still prodding her even when her eyes are open wide, and she thinks he might laugh, but he doesn’t.

Sometimes the girls who come from the airport approach the desk and start talking before Danny can usher them into the ideal script. There have been girls who start talking before Danny can help them, launching into details about their uncle in Wythenshawe. It’s always an uncle, never an aunt, like the mention of femaleness would be too close to the bone, give them away. Sick uncles in the hospital. They’ll be going back and forth between the hospital. Can he recommend a taxi service?

Anita has been at the hotel long enough to have known front-of-house staff who didn’t work like Danny does. Who would turn the teenagers away. Who would recommend hostels and let them fidget and writhe in long silences. Anita didn’t hear it herself, but Pim told her that a few years ago a bony man who’d been called in for temp cover had said “I know why you’re here” to a girl who couldn’t have been sixteen. Pim couldn’t tell if she’d come from the hospital or was on her way, but she’d left and been sick in the road.

Danny has a bend in his nose and he keeps a can of Tizer hidden by his keyboard. His secret. Once, when Lukas was rolling rollies for her and Stu by the skips, where the steam from the laundry clouds and whines without end, two sirens sounded in the distance in a striking kind of harmony. Stu was talking about his wife’s slow-cooker. Lukas was licking the papers too slowly: Anita had learned months ago not to watch him do it, but her mind had wandered and she caught sight of the thing. She has to wipe her cigarette down on her apron without causing offense, somehow. The sirens became louder. They kept getting louder until they were right there in front, on the far side of the hotel, screeching to a halt under the bronze letters reading Colonnia Airport Hotel. The three of them jogged around the side, and saw an ambulance and a police car, both empty, doors open.

Danny only had a few hurt fingers, not even breaks, just scratches really, because one of the men had gone at him with a set of keys. The brothers were the ones who’d required the ambulance; they’d mostly hurt each other in the incident, the one which Anita wasn’t there to witness. One cut his leg while trying to vault the front desk. The others had just started punching and caught Danny in the fleshiest part of his gut, below the belly-button, hardly hard enough to notice. The details were hazy. Anita asked if the men were gypsies and if they’d found the girl they were looking for and Stu told her she couldn’t call them that. That she should know better.

◆

There’s another woman in a bathtub. This time Anita can hear the squeaking the moment she steps into the room. This time she doesn’t need to wake her. Maybe if Anita could knock louder, if the women could give some sign of life more quickly, this humiliating trap could be avoided. But it’s too late (always too late) and Anita sees it through the mirror by the wardrobe: the woman collecting her nest.

She’s gathering both a towel and sheets that don’t belong to the hotel, the woman’s own, mint and burgundy respectively, colours that are so rare to see in the hotel that it feels like seeing them for the first time. That, and toilet paper. Clouds of it, shoved under her arm and packed into the small bins. Anita is about to say the words, the words that almost never enact the magic that they’re meant to enact. She’s about to say: “I’ll come back later”, but by some inexplicable silent force, she knows that that’s not what the woman in the bathroom wants.

Then she’s there, standing in front of her, apologising, giggling without a trace of laughter.

“It’s funny,” she says, gesturing to the bathroom, wiping her face, tripping over herself to say: “I’ll let you do your job.”

But she doesn’t move. Anita walks to the TV, picks up the bin. There have been guests who enjoy watching her work, but not often, and not like this. The woman is still frozen to the spot. Anita takes a packet of antibacterial wipes from her apron and starts on the desk. She works like that until she’s at the window. She still has not heard the woman move.

The stillness becomes contagious, and Anita can’t continue. It’s too much of a farce. She brings herself upright.

The woman is looking at a blank patch of wall. “I’m fine,” she says. “Fine on the flight. Fine during. But…” she trails off. “I didn’t even…” The woman can only mouth the last word. Anita understands it, though.

Bleed. The word is bleed.

“Would you believe I work at Microsoft? Microsoft.”

Anita begins to dig through her pocket. She doesn’t know what she’s looking for. “I…” she starts uselessly. The woman on the other side of the room doesn’t seem to have noticed.

“My husband was supposed to come but we thought one of us should… We had to use cash. Like some…like I don’t know what.” Her voice becomes mostly breath. “We had to use cash. To stay in this place, we had to use cash, then it was…”

She struggles to find the words and begins to pull at the loose skin of her elbow. She’s facing Anita now, but not quite looking at her. Her gaze reaches the mini fridge. “It was what it was, it was…bad, but I was okay. I was okay. And then that sign –”

Her voice breaks. Her face breaks. Her eyes meet Anita’s. Then they land on the sign, Soilage Charge £150, untouched, by the bed. She lowers herself to sit. She doubles over and starts to shake.

Anita’s feet are heavy. Her lips are dry; she’s been breathing through her mouth this whole time. Like before, her fingers start to dig through her apron. Her eyes can’t focus. She doesn’t know what she’s looking for.

She wills herself to walk over to the woman. She wants to put a hand on her back but overthinks it. From nowhere, she sees her sister doing it, able to do it with ease. Her sister, but not her. Anita is too clumsy for that. She lets the woman sob. The tag on the back of her shirt is torn. It’s caught on a thin silver chain.

Fingers move through the apron, still, and then – there. She finds it. There. A chocolate. A triangular chocolate, the size of a 50p coin.

She pulls it out lamely and extends her arm halfway. She waits for the woman to notice. It takes enough time for the room to become hot. The woman lifts her head, and both of them stare at it, both shaking, words torn from their throats.

They remain like that, until the woman on the bed makes a sound almost like laughter. Laughter and something else, something primal. The spirit leaving the body, or a spirit becoming reanimated. Anita’s arm stays like that, but the woman doesn’t take the thing.

They remain like that until the duck calls for noon. The sound makes both of them jump.

How long ago was that night? The one where the woman was parked outside the Warhammer shop. It could have been a year. It could have been a week.

Whatever the length of time, that’s how long it’s taken for the swaying woman to make it here. She’s shifting her weight from side to side again, with a stack of something tucked underneath one arm. She looks old today. Maybe anyone looks old when they’re alone beside an empty loading bay.

Sometimes guests make their way here, to the side of the building, looking for a way out to the main road, and someone will gently guide them back. This woman knows where she is.

It occurs to Anita that she’s seen her many times before. Or maybe women like her. They want to talk to you, always you, everyone feels, once it’s too late, and the talking has already begun. These women will sometimes have a poster-board covered in writing, either printed or hand-written. This one has something like that today: Anita can see that from this distance. It’s a bit like the homeless with cardboard signs, but this woman is polished. Anita recognises her cardigan from the Marks and Spencer window display. It’s covered in a pineapple pattern. The display called them “Must-Have Cardies”. Anita thought this was a word she’d never learned. Now it clicks. The feeling is a nice distraction from the corpses.

The tray of flies is wobbling in her hands. The thing is only as deep as a brownie tray, but far too long for one person to handle, and it’s swaying in watery layers: the drain flies, the compost-soup they’ve become, and whatever toxin went into the water to lure them in in the first place. Stu had cornered her in the stockroom and said they needed to go into the hedge. Easy peasy. He’d been close enough that she could see his missing a patch of eyelashes. She’d never noticed before. He’d made a gagging noise at the tray that might have been a joke or might have been real and involuntary. It doesn’t matter. Anita asked about the hedge. Will it be bad for the hedge? She said this not sure if she was saying the word right. The h like that: a sound but a breath. It made her think of the last woman in the bathtub and she let Stu shrug and leave her there. She tried to measure the tray with her eyes: not quite her own height. Not much less.

The woman in the distance is shifting left to right. The tray is somehow heavier than Anita had imagined, and she’d not been optimistic. The woman is shouting Yoohoo! now, just like that. Anita’s neck and shoulder seize. Talons beneath her skin. She can’t stop moving. The woman is jogging over. Anita watches some of the intact fly bodies sway and float. They don’t know if they’re animal or mineral.

A few drops land on Anita’s knuckle. Yoohoo! The woman is closer. She jogs fast. Maybe she’s not as old as she looks. The hedge is close now, too. So close. “Please one moment,” Anita says.

“Excuse me!” the woman is saying too loud, louder than she needs to.

She reaches the kerb where the hedge begins, but no, no – something slips – and in a blink her knee meets her forearm, a supportive reflex, and for a moment Anita can rest like that, steady. She breathes. She is able to shift her weight and clasp the tray anew. A tension lifts. A stronger grip. There now. It’s under control. She takes another breath. The woman is by her side now.

“Can you help me?” So loud. “Do you know–”

One of the sheets slips out from the woman’s arm, onto the concrete. She picks it up so swiftly that she doesn’t even stutter – she’s asking about arrival times, a flight, girls are on their own when they arrive sometimes, have you noticed them? She wants to help them, to speak to them. But Anita’s seen it: the image. The sheet that slipped. The lamination. The small feet, the amphibian fingers, and the noose. The black text, the colon dividing numbers.

“Do you know what time it gets in?”

Anita’s shoulder seizes. “What?” she says.

“The Shannon flight?” The woman pronounces every sound slowly and with increasing volume. Pointing her finger first at Anita, then at the sky above, she adds, “Do YOU know when IT GETS IN?”

In the distance, a pager goes off. Someone else’s. She’s left hers inside. She can’t guess which hour has passed. The sun is behind Anita now, and the woman is squinting. She’s waiting for an answer.

The flies go everywhere. The black sludge explodes on the ground before the sound of the crashing tray can reach her ears. The woman shrieks and jumps backwards.

“For goodness sake!” she’s crying. “What is that?”

Anita’s ankles are wet, too, and she stands like that, legs straight, watching the cotton absorb the liquid, watching the liquid trickle on the gentle incline. She stays there, like that, until the woman’s crying dies down, until she starts asking in earnest, “What is wrong with you?” Anita stands there until the sun feels like it’s burning her shoulders underneath her uniform. The woman is shouting more, but after a time the sounds turn to clicks, clicks on pavement, and then the woman is gone.

Anita stands there until her socks begin to dry. She stays that way until the only thing left of the drain flies is an unremarkable clump that could be mistaken for soil or for earth.