The beanstalk sprouted in my backyard the day of the party and, like pretty much everything else, I didn’t want to talk about it. The whole damn party had been Marsha’s–my sort-of-mother-in-law’s–idea. We’ll send you off in style, dears, she said, and, like always, I was thrown into it by some kind of inertia that had been set in place when I was nineteen years old and had climbed on the back of her son’s motorcycle for the first time, an inertia I was still at the mercy of even now, over ten years later, propelled out of my life and into someone else’s, forward from Cincinnati to Cleveland, from an okay-ish life to a less okay-ish life and a beanstalk in my backyard. Beanstalk, of course, wasn’t the right word—I hadn’t planted any beans.

Before I tested positive for pregnancy, I had already buried three hamsters, a tree frog, and a hermit crab in my backyard in less than a year with no consequences. The first hamster I found on my pillowcase where the cat left it while I was sleeping. He wasn’t mutilated or anything. Just looked like she had licked him all the way across his back, but kind of gently. Lily’s a good cat. I imagined she was trying to return him to me after he’d escaped the previous afternoon because I’d accidentally left the cage door open. We’d called him Peanut.

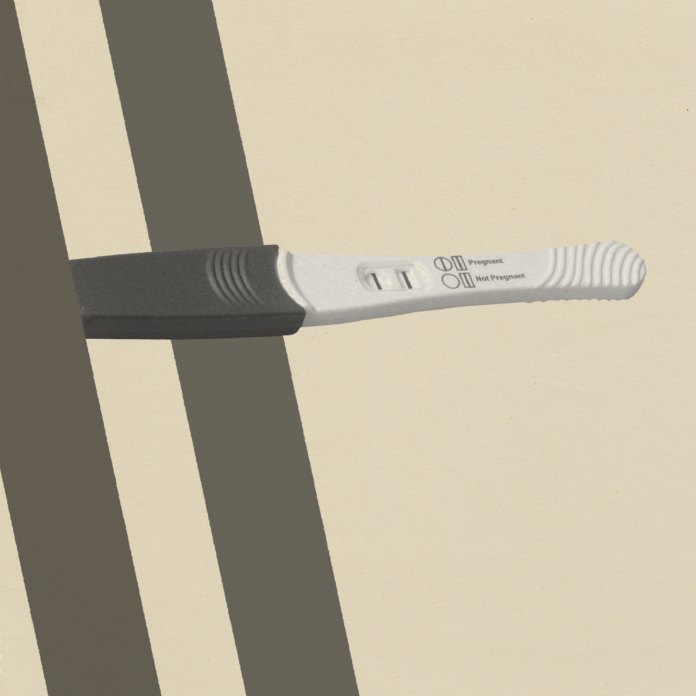

The night before the beanstalk, three minutes after I’d peed on a stick I’d bought from the nearby gas station, standing in the doorway of our bathroom, I thought of Peanut again. Oh my god Leo, I said, is that gonna happen to the baby? I watched him doing nothing in our chocolate-colored recliner. Panties still around my ankles. I had dropped the pregnancy test in the toilet.

Lily would never hurt a baby, he said. The cat was sleeping upside down in a late-afternoon sunbeam on top of one of the moving boxes, LIVING ROOM scribbled across it in big letters.

You know what I meant, I said, even though I wasn’t sure he had. I hadn’t washed my hands yet. I twisted and twisted the bathroom doorknob in my hand, miffed.

Hush, he said. No.

We didn’t plan for this.

No, he said again, kinder this time. But it makes sense. The next step. There was an inevitability to his tone that I usually reserve for red lights and death.

The tree frog died because I put coconut oil on the side of his food dish to keep the crickets from jumping out and he had absorbed some through his skin. At least I thought that was what killed him—I did the thing with the coconut oil and thirty minutes later he was gone, so… I found the hermit crab falling out of his shell and smelling like rotting fish. No discernable causes of death. Less than ideal tank conditions, maybe? The deaths of the second and third hamsters, who looked just like Peanut, so much so that some people couldn’t even tell the difference, were just as bad. Worse. I went to sleep one evening, leaving the first replacement hamster curled into a sleeping fluff ball, and woke to find it stiff and already cold. The third one, two months later, went the same way; I found him when I came home from work, a long day in the field as an in-home healthcare aid for the elderly. That hamster had one eye closed and the other open. I was inconsolable because, in those cases, I didn’t know what I’d done wrong.

Sudden hamster death syndrome, I said now, after reminding Leo of my track record with small animal expiration.

Sweetie, please, Leo said, looking at me for the first time. Our baby is not a hamster. Or a tree frog. Or a hermit crab.

Obviously, I knew that. That’s not what I meant, again.

◆

That night we made love surrounded by boxes labeled BEDROOM stacked four feet high with all the ready-made movements of thirteen years together, a sharp and rapid knowing. I didn’t want to, because it was just that kind of frisky business that had gotten me into this mess in the first place, but then I thought, well, the worst has already happened, so why not enjoy it? And when we were done I rolled him over and we fucked again.

We’re gonna make this work, he said afterwards, arm draped around my stomach. We can afford it. With my new job, you might not even need to find a job after the move.

Sure, I said.

Drifting off, I had a nightmare about the hamsters. I dreamed they clawed their way out of the ground where they were buried in boxes that once held Christmas lights, jewelry, shoes, whatever we had had lying around at the time of death. They emerged stiff and kind of hunchbacked, in the almost-fetal positions they had died in, Peanut’s hair like he had recently been licked and it hadn’t had the chance to dry. They marched in a line through grass tall as trees, the hermit crab riding on Peanut’s shoulders and waving a purple claw, until they found me in bed. I woke shivering, while Leo slept on.

I wobbled back into the bathroom, hands on my stomach, wondering how big it was in there—the size of a pea, right, or a bean? Something like that. I pressed the handle on the toilet, watched the water flush, gurgle, refill, the test floating still. I grabbed it from the toilet with bare hands and padded barefoot to the kitchen, where I watched the wind shake the trees through the backyard patio door. It was summer, so I opened the door and headed toward the tree where Leo had buried our hamsters, the hermit crab, the tree frog, all more or less in a row. The last one had been in the fall, just before the weather turned and the ground froze. I’d watched him scratch out the hole with my garden spade from the kitchen, hoping he wouldn’t hit one of the containers holding the others, going deep enough that the cat or raccoons wouldn’t dig it up.

Digging again with the same spade I’d pulled from the box marked KITCHEN, I thought, happily: This is the last thing I will bury here. It was our final weekend in our one-bedroom apartment in the right half of the duplex. The yard the animals were buried in was shared between us and our neighbors, two college girls who were almost never home. We were moving upstate to a house that was all our own, three bedrooms, two baths. Leo had gotten a promotion—out of the field, into the corporate office. It would be more space than I’d ever had. In childhood, my dad and I had lived in a single bedroom apartment on the third floor, him always on the futon, but at nineteen I moved in with Leo and here we had stayed. I had often wondered what we’d do with so much room in the new house, how we would fill it, if we would expand and grow to our environment, like goldfish. I guess now we knew.

When the hole was deep enough, I put in the pregnancy test. The white of the plastic was so bright in the dark it looked almost glowing and I felt the sharp stab of relief with each splash of dirt I tossed in on top, covering it. Bye bye, test. Bye bye, glow. Everything I’d ever failed at was buried beneath this grass. The test would be in good company, long after I left. When the dirt was smooth and flat again, I clapped my muddy hands on my thighs.

For a second, I felt unable to rise, as if the ground were pulling me to my knees. I remained crouched in the dirt, reluctant to stand. I imagined digging my fingernails into the loose ground, mud damp and cold like a basement on the back of my hands, uncovering the test and continuing to dig without the spade, deeper deeper deeper, until I went so far I felt the brush of soggy cardboard coffins against my fingertips, soft and repulsive. The boxes with my pets in them would fall to pieces in my hand when I uncovered them, and I would cup my loves in my palms without embracing them. I could hold them and tell them how very sorry I was. Instead, repulsed at the thought of their tiny skeletons, I withdrew my hands and went inside.

In the bedroom again, moonlight sliced by blinds made the bed look bound by ghostly chains. The next morning, the day of the going-away party, the beanstalk, vines like veins, green as an ogre, had sprouted from the same spot under the tree, forcing its way through the tallest branches and outgrowing even our house, disappearing into the clouds.

◆

The goodbye party was to be in the backyard, in the new shade of the beanstalk, with foldable tables covered in plastic orange tablecloths, flies peppering the paper plates full of cantaloupe, watermelon, honeydew, all of which I hated. (The college girls from next door were out of town or hungover or either way not outside. Maybe they’d climbed the beanstalk and been eaten by angels or aliens or giants.) When I woke, everything was set up for the party but Leo wasn’t anywhere around, not in the house or the yard. I circled the beanstalk, curious but not alarmed, and instead of thinking about its presence I briefly wondered if that would be the last I saw of Leo, if my dad had been right all along, only it had taken nearly fifteen years together for the leather-clad, motorcycle-riding boyfriend of my youth to break my heart. Maybe best Dad hadn’t lived to see it then. There’d have been no living with him after his smug “Told you so.”

Marsha materialized beside me like she was wont to do and said, Good morning sleepyhead, like I had overslept, though it was not yet nine. I thought about telling her that her son had run off and left me with an accidental pregnancy and an overgrown weed and what did she think about that? But I didn’t.

Hey Marsha, I said without turning to look at her. We stared at the beanstalk together for a second before she clucked her tongue like a housewife in a sitcom. What do you know about this? she asked. Something those girls next door cooked up, I imagine?

I guess, I said. Was it here this morning?

Oh yes, she said. Since I got here a couple of hours ago. Ugly, isn’t it?

Sure.

It’ll give us some nice shade for the party at least, she said. If I’d had anyone else as a sort-of-mother-in-law, she might’ve patted my arm on her way inside, but when Marsha turned and left without reaching for me, I was glad. I didn’t really mind Marsha, mostly because in all the time I’d been with Leo, she’d only ever touched me once, about five years in, when we told her we had no intentions of marrying, and she grazed my knuckles and said, Honey, are you sure? This is just like men, you know. My dad had been gone eight years, and my mom was out of the picture (classic birth-and-run), so Marsha and Leo were as good as it got for me.

A car door slammed and a few minutes later, Leo, not halfway across the state after all, materialized beside me in that same sudden way his mother had, holding two cups and a bottle in one hand, an axe in the other. He found me with my neck heavy on my spine, still staring up the length of the beanstalk, the top of which I couldn’t see. The stalk was wider around than a tree trunk, twisted and curved like branches. The wind flapped the tablecloths behind me, blew hair into my eyes, but did not sway the stalk.

Do you think the landlord will be mad? I said. I didn’t tell him about the buried pregnancy test.

Nah, I hope not. We need that deposit back. He leaned the axe against its trunk. Was it called a trunk? I’m gonna take care of it, though.

Take care of it how? He gestured at the axe. I barely gave it a glance. Why?

He hummed without opening his mouth. It just seemed like the thing to do.

Me man, I said, my voice fakely gruff. Me smash. He smiled goodnaturedly and I smiled too, then Leo handed me a red solo cup, wine glasses already packed, and held up a bottle of grape juice.

A toast first, he said. That’s what we need.

This is a cause for celebration, is it? I said, embarrassed to find my voice suddenly shrill, but he didn’t hear, or pretended not to.

I asked Barney. They didn’t have any sparkling, he said, pouring it out into the cups. He was on a first name basis with the employees at the corner gas station because he always stopped for cigarettes every morning on his way to the landfill where he worked, and then stopped again on his way home to get a second pack because, by the workday’s end, he’d already gone through what he’d bought that morning. They had even gifted him a carton of Pall Malls as a going away present.

Cheers, Jacks, he said, clinking our cups. He smelled like old spice, sewer, and dirt, pungent and familiar.

All right, I said. I held the cup in my hands without drinking it while he downed his in one swallow, picked up the axe, and swung it into the beanstalk, once, twice. It didn’t even leave a dent, not a single mark in the vine. He kept trying, sweat seeping through the back of his shirt, the occasional heavy-breathing sound I associated with lovemaking escaping his lips.

While he worked I said, Do you remember when we brought home Peanut? And the whole story came pouring out while I stared at the nape of his neck: how Peanut was so soft and tame we couldn’t stop holding him at all that first day or night, and did Leo remember how the next day the stress of all our handling gave him wet-tail? Or remember when we went to Las Vegas for the weekend and we left Baggins the second hamster at the house and when we came back his water bottle was empty, and maybe it had only been an hour since it had run out, but maybe it had been more, because how could we be sure he hadn’t drank it all on Thursday and had been sitting there thirsty for three days? Or how the tree frog didn’t even last twenty-four hours? Or when we put Dougie, the third hamster, in his plastic ball to play and he rolled down the porch stairs in it while I was taking out the trash? Or when I dropped him on the kitchen tile after he’d bitten me hard enough to draw blood? And then he got stuck under the stove? Or when I used to get the hermit crab out and let it crawl all over my fingers until someone online told me that hermit crabs need high humidity to breathe and by removing it from the glass tank I was slowly suffocating it?

I inhaled. He stopped chopping, and when he lowered the axe, the beanstalk had not weakened at all, not one mark.

It’s for the best, I said. If you did chop it down, what’s to say it wouldn’t fall on our house and wreck everything?

Leo’s fine features, eyes scrunched, mouth taut, loosened and fell into an almost-smile when he finally turned to face me. I had watched his cheeks go from the chiseled bones of a boy not yet twenty to this, pappy and plump as play-dough. He had softened now like baked bread, even in his eyes. I felt a sudden floating feeling like affection for him; he was sturdy, dependable, like the ache behind your eyes when you don’t get enough sleep.

I just wanted to get it down before the landlord does the walk-through Monday, he said. He wiped his brow with the back of his arm and squinted up at the beanstalk. I don’t want him to think we’ve planted something without permission. Maybe I can call someone with a chainsaw tomorrow?

I put my palm on it, felt it cold and tough like a broccoli stalk against my skin. It had started growing buds like tiny nipples.

Where do you think it goes?

He shrugged. Does it matter?

I’m sure it’s fine, I said, dropping my hand. Then, Did you hear what I said about Peanut?

He drew me into his chest, carrying in it a heartbeat I noticed in ways I never noticed my own. To the top of my head he said, Oh Jacky, this baby, and inhaled. This baby, he said again, and I could tell he was smiling, but he couldn’t get it out. He pushed me from him but kept me at arm’s length, hands on my shoulders. Jacks, he said. Marry me. Yeah? Today? All our friends will be here already. I think we should get married. Before the baby comes, you know. I want to do this properly–the house, the family, the whole thing. He pulled me back to his body and squeezed me until I lost my breath, put his lips on my hair, and said, I guess I should probably quit smoking.

Over his shoulder I watched the beanstalk. It was definitely growing, and quickly. The nubs had sprouted like the green buds on the end of tree branches in spring. There were three or four, expanding even as I watched: the size of a grape, a plum, a peach.

It’s not true what they say about goldfish. They don’t actually grow based on the size of their environment. Keeping a goldfish in a bowl does not guarantee that it will remain small enough for that bowl forever. The truth is, a goldfish is gonna grow as large as it’s gonna grow, and there’s nothing anybody can do to stop it. Keeping it in a too-small space will not ensure its size, only its unhappiness.

◆

Hamsters are most active at dusk and dawn. Before their deaths, I stayed awake most nights listening to the sound of the rattling hamster wheel in the other room, whir-whir-whir-whir, Leo snoring in my other ear. He said the sound never bothered him, that he didn’t even notice. I noticed. It kept me awake, but not because it was bothersome. The rattle of the wheel was like a promise, whispering in its squeaking way that the hamster was okay, propelled through the dark by palm-pink toes, running and running ten miles or more a night, going nowhere for no reason except the need to move.

I did not share a hamster’s fondness for kinetic energy. I’d balked when Leo told me about the promotion and that it would require us to leave the Cincinnati neighborhood we loved, where we could walk to the grocery store and the bank, and our favorite Mexican restaurant with the best chalupas in the world, and move to Cleveland, where I had never been, but where I assumed it was always gray and probably cold, ruined by the lake effect of the north. Still, I encouraged him to go for it, or rather I didn’t discourage him, and it was never a question of if I would go with him. Still, willingness was not excitement, and when it came to change, I found myself more of a hamster at noon, buried in a deep nest of soft bedding, than one at midnight, running with compulsion toward this unknown thing.

After Leo released me from his proposal hug, I said, You think so? and he kissed me, deliberately, like he hadn’t since he was nineteen, and said, Yes, absolutely. So I nodded, smiled, and told him I needed to go in for a glass of water.

◆

As people started to arrive, Marsha found me at the drinks table ladling punch into my plastic cup, thinking about spiking it with a flask of vodka I had swiped from our liquor cabinet when Leo wasn’t looking, bean in my belly be damned, and I could tell by the way she was coming at me arms-open that Leo must have told her, well, something. I threw the flask into the bushes before she got any closer.

Praise his name. She was shouting. She never did anything quiet. Jacky, a grandchild! Hands up in the air, head thrown back but not looking at the beanstalk, talking to God, I guess. I looked around to make sure no else was near enough to hear, relieved to see that most people were still inside. And a wedding!

He had told her both things, then.

When she reached me, she wrapped an arm around my neck and kissed my cheek. I’d given up on you two, you know.

Thanks, Marsha, I said, but I wasn’t really. Thankful, I mean. But I did get it. Leo was her only child, and he wasn’t exactly, as Marsha would’ve said, a spring chicken anymore. We hadn’t even been trying. I wonder if he told her that?

Why didn’t you say something this morning? she said.

I gestured without intention but she took it to mean the beanstalk.

Oh, right. Leo couldn’t get that down before the party? she asked. I told her I’d told him to leave it, and she nodded. Well, lucky for you, you won’t have to live with it long now, will you? she said. She smiled. You’re going to be such a good mother.

I am?

Of course, I mean, look at you, she said. You’re so good at your job, so kind to your sweet old clients. And there’s, you know, your thing with the animals.

They died, I said.

Marsha smiled again and put her hand on my stomach. But you loved them so much, she said. Three times touched in ten years, and two of those in the last thirty seconds. Is this what a baby did to a person?

I excused myself and circled behind the beanstalk. The fruit-sized buds had grown, bulged into the shape of raindrops the size of barn owls. The skin on the stalk had grown translucent with the stretching and I could almost see inside it, dark shadows appearing and disappearing like a sonogram. Suddenly I understood that there was life in there, that it was coming no matter how hard I ignored it. Oh come on, I said—and tore the orb off. I threw it on the ground and crushed it under my heel, where it sunk into the dirt in tiny insignificant pieces. I didn’t look down at the remains. Whatever was in there, I didn’t want to know.

Three more blossomed almost immediately and I picked them off too, crushed them in both hands. I worried when I dropped them to the ground that they’d sprout new beanstalks, like fallen acorns, but told myself they wouldn’t. It was much more likely they’d wither without a host, like plucked flowers or parasites.

◆

Across the yard, a game of cornhole was just getting started. Leo waved me over, Jacks, be my partner, he said, and because I already was, I reluctantly drifted that way, took the offered corn sacks from his hand. My palms were sticky from the pulp or juice or fluids that had come out of the beanstalk orbs when I crushed them. I rubbed them against the corn sacks. I hate this game, I said.

You’ll do fine, Leo said, and leaned in to whisper in my ear. I was thinking we could do the ceremony after dinner? Denny’s a Justice of the Peace. He kissed my temple and jogged across to the other board. We were playing against two of his work buddies, men I had made dinner for but whose names I couldn’t remember—was one of them the Justice of the Peace? The man beside me threw first, put two in the hole and one on the board; the other flopped paralytic on the grass. Then I threw, missed all four, but did manage to knock one of his off the board, too.

We’re throwing a big party for Leo, he said while our partners collected the corn sacks to throw back. Surprisingly, I found myself feeling sort of fond of this game, the tossing back and forth of the same sacks of corn flour. Another one, I mean. For his last day of work, the man added when I didn’t acknowledge him. Cake and all.

I said, I know he’s sad to leave you boys.

I hadn’t gotten a cake on my last day of work; I hadn’t even told anyone I was leaving. Instead I did my rounds like any other day, sitting for an hour with Nancy, who lived on her own and paid for an aide to stop by three times a week but who didn’t actually need any help around the house except to have someone listen to the stories of her youth. Oh you just look at this, Nancy always said, me yammering on like an old woman. I sound like my grandmother. She always said, ‘‘Oh, at your age all I ever wanted was to have babies, and I reckon I did just that.” I remember thinking not me, Mamaw, no way. And here I am. A lonely old lady. And when she was finished talking I would smile, pat her knee, and tell her my time was up.

Then I went to the home of a kind, frail old man to help him get dressed and make his breakfast, always two scrambled eggs, while his perfectly healthy wife looked over my shoulder and complained that it wasn’t how she would have made them. And I just smiled and apologized, because I knew I would never have to see her again.

When I’d left my job last week I’d been relieved I wouldn’t work again until after the move, but now, Leo throwing corn sack after corn sack at me, I felt a little panicky. Who would even want to hire me if they knew I’d have to leave in a few months for the baby? I wouldn’t feel right even looking for a job. Who goes into something knowing they’re going to abandon it? Who does that?

Jacks? Leo said. Your turn? You okay?

Right, sorry, I said, and I threw them back—three out of four straight into the hole. Everyone shouted and I allowed myself to settle into the pleasure of a stationary game, which we ultimately lost, but which I found a kind of comfort in. I could live like cornhole, I thought. Allowing myself to be tossed back and forth, never moving unless someone launches me forward, always aiming for a pre-chosen target. Rinse and repeat. I could do that. Even the hard slam of canvas sack on wood doesn’t sound like it hurts so much.

◆

A short time later I stood alone at the beanstalk, watery-eyed from staring at the sun, trying to see the top. The orbs were sprouting every few minutes and now and again some of the larger ones fell like overripe apples, hitting the dirt around me with the consistency of slow rain. I curled and uncurled my fingers. I was going to do it: climb the stalk, follow the target I had been pointed towards, reach the top. Claim my reward: goose, gold, giant.

I put my right hand on a vine, thick and veiny, then my left hand on another, higher. The leaves and vines wrapped the stalk with enough consistency to make climbing easy. I was three feet, six feet, ten feet up before I thought anything of it. I’d lived like that my whole life, after all: following the path at my feet without looking back or down or around. I heard party sounds below, kept climbing until I heard no sounds. I passed the top of the tree, high enough to see the entire neighborhood, people in my backyard like ants. Then so high I couldn’t see the people at all, neighborhood houses like ants. Then no neighborhood. And still I couldn’t see the top of the beanstalk. Once at the top would I find an answer to all my problems, like an enchanted hen or a magic harp or at the very least a happy couple? Or would I find the wife of a giant who wished she wasn’t?

As I climbed, I watched the orbs pulsating on their branches like leaves all around me. And I thought: What if I did let them hatch? So what if something alive, an alien maybe, big-eyed and soft, scraped its way out of an orb and from the ruins of its beanstalk womb asked me for a home? So what if it wanted to consume me and gobble me up and the whole world too? If that’s the way my life was going, so what?

I paused to pluck the nearest orb from its stem and held it in my palm the way cowboys cup river water in old movies. It was heavier than I expected, and cold. I didn’t quite have a good grip on it. Imagine the size of their alien hearts in there, like my hamsters’, like my pinky-nail. Bones fragile as pencil lead. Sometimes when I held my hamsters I was consumed by the urge to squeeze. It was the same feeling I had now. To let yourself love something so much the only outlet was destruction. It would be easy to love that hard. To let it happen and then keep going, without even realizing what you’d done. Like footsteps in grass above graves.

◆

This high up the beanstalk, the orbs were even bigger, growing at a rate faster than those near the ground—more sunlight, maybe. The biggest ones were beginning to tremble and crack as I watched, holding the stalk with one hand, an orb in the other. The one in my palm split open. A tiny winged creature with a feathery head emerged from the husk, blinking at me with shiny eyes like the glass marbles on a Beanie Boo. Its mouth open and closed, toothless but sharp, like a baby bird’s beak.

What? I said. What do you want from me? It kept scratching out of its shell with the tiniest of talons, and all around me, the other orbs shook, hatching too. This is the way it’s going to be, then, I thought. This is it. They don’t seem so bad.

I was hoping to discover that once I began climbing and saw what was waiting at the top I wouldn’t be able to stop even if I’d wanted to—like when a hamster tries to stop running on its wheel, but the wheel keeps moving, and the hamster is flung off or spins on its back inside the wheel anyway, propelled by the power of its past actions. So it often goes for creatures with an inclination for inertia. So it has often gone for me.

But this time? I stared at the eyes of the creature with all its hunger and its need and I thought about how easy it was to split yourself wide open with a fierce and terrible tenderness, how dangerous it was to love something so fragile. I remembered Nancy, self-proclaimed lonely old woman, and thought how she would love this beanstalk baby, this chance to need and be needed. Let her be the one to climb up here to get you then, I told it, and just as soon as I did, I realized I didn’t have that squeezing feeling in my fingers anymore. I said to the beanstalk creature, Sorry, goose. I don’t think I’ll be seeing you again. Send my regret to the giant. And I left it there. Didn’t even look back. If it watched me go, mouth open and eyes sad, I would never know. I would never know what waited for me at the top. I could live without knowing, I realized. More than that: I wanted not to know, to never know.

The descent was easier than the ascent. It was getting dark by the time my own backyard came into view. The party was breaking up; the final stragglers, I could see through the window, congregated inside the kitchen now, finishing off leftovers, room-temperature fruit and lukewarm punch (and from the sound of things, they had had the same idea I did about spiking it). When I got within five or six feet I let go, landed on the soles of my feet so that it made my shins tingle. I was dusting off my palms when Leo drifted over, opening and closing the screen door quietly, cigarette between his teeth. He put one warm hand on my arm and the other on my stomach, which I resented.

There you are, he said. I thought maybe you had gone to the bedroom to rest. I shook my head, assured him it’s all fine, I’m fine, and accepted his kiss. He pulled away and said, Listen, Denny’s inside, he’s ready to do the ceremony now, I think we should do it tonight because this is the last time we’ll be with all our friends for a while, and tomorrow, I was thinking we should probably go to the doctor—and I put a hand on each of his cheeks and kissed him again.

Sssh, I said, fine. But could you give me a minute? There’s something I need to do first. He snuffed his cigarette, squeezed my hand, and rejoined the party. When he had gone back inside, I shuffled around in the bush until I found the flask of vodka. I took three long, deliberate gulps, then grabbed the axe Leo had brought out earlier and propped against the stalk. I’d never swung an axe before, but I lifted it behind my shoulder like a golf club and felt a certainty, for the first time in my life. The wooden handle was rough in my palms and uneven in a way I knew would cause splinters and blisters. I didn’t care. I needed something like blood on my hands. After all, this was a beanstalk, and I was Jacky, and though there was no telling which way it would fall, this baby was coming down.