Korovin roused to a stench of cat piss pervading the bedroom. The cat was incorrigible. After a multitude of tests and checkups, which had cost a fortune, the vet assured Korovin of the animal’s perfect health. Korovin was the only soul living with the cat for the past three years after Nancy took off with their four-year-old son and all his belongings, except for an expensive railroad village Korovin had purchased for Daniel’s birthday but never assembled. So, unless the cat remonstrated against its being left behind and sharing the house with Korovin, there could be no other logical reason for it to start pissing every-damn-where.

The cat was a gluttonous beast, long and scrawny, with smooth black seal-like hide. It had sparse whiskers and sharp yellow eyes that followed Korovin in and out of the room. The animal’s body had no visible deformities, except for the hind legs that seemed too thin and wobbly, the paws turned out. The cat stayed perpetually famished, and when it demanded food, it mewed in the most miserable, pleading manner, which irritated Korovin to the roots of his hair, but also made him aware of his own loneliness in the world.

Korovin took the Friday off to keep his son Daniel over the Memorial Day weekend because Nancy and her new husband, a psychiatrist, were going on a three-day cruise to the Bahamas. Korovin felt nervous. It had been a while since he’d stayed with the boy for such a long time without his mother being somewhere close by, if not in the same house, at least in the same city. He knew he could always call her should things become complicated. His own mother, who didn’t drive and could hardly speak English, wasn’t much of a help. She was scared of Daniel and constantly worried about doing something wrong. Korovin remembered telling his mother for the first time that Daniel had a developmental disorder and that he could be severely retarded. She closed her eyes and then pressed her palms to her ears, shaking her head so hard, Korovin had to catch it in his hands to stop her. “It’s that water we’re drinking and the food, all the antibiotics and hormones, the antidepressants,” she’d said. “We shouldn’t have left Russia. Why did you have to marry an American?”

Korovin couldn’t provide her with a simple answer. Because there were many answers, none of which would’ve satisfied his mother. He’d been a first-year exchange student in America when he met Nancy, whose family had agreed to host him for a year. Prior to coming to America, Korovin had never traveled outside Russia, first because Russians weren’t allowed to, and then, after perestroika, because his family was dog-poor; they couldn’t always afford meat for dinner and subsisted on beets, potatoes, homemade sauerkraut. When he began living with the McDonalds, Korovin felt strangely safe, secure, even though he barely understood English. They seemed sincere and easygoing and not at all American. They exhibited none of the capitalist arrogance and frivolity derided in Russian movies and talk shows. Their house was the Winter Palace compared to Korovin’s parents’ one-bedroom flat in Moscow. The McDonalds’ lifestyle appeared accessible and even righteous. It was a family of good jobs, good values, schedules and plans made months in advance while Korovin’s family was a miniature replica of his native country—one never knew what kind of storm or upheaval one would wake up to. There were things as minor as his mother washing windows at five o’clock in the morning or as major as his father joining the Mormons and moving to Siberia, cohabitating in some isolated, snow-swept commune. The last they’d heard of him, he had three wives and three more children.

The McDonalds, on the other hand, were a devoted team. They cooked dinners together and ate out on weekends, took turns doing laundry, loading and unloading the dishwasher, the chore that had become solely Korovin’s while he was staying at their place. They cleaned their own house, mowed their yard, recycled, and organized large neighborly cook-outs, during which men grilled burgers and hot dogs, conversing in loud, passionate voices about ballgames and house projects, and no one was getting drunk to the brink of madness, passing out at the table or pissing in flowerbeds. American hospitality was new to Korovin, and he fell in love with the world that appeared so different from the one he’d grown up in, where people had been living in fear and corruption for so long, they didn’t know how to live without either one. Democracy meant power unlimited for those who’d been quick enough to adjust, but most of Korovin’s friends ended up trading hard currency or opening kiosks, where they sold anything from pantyhose to fried chickens to vodka to marijuana.

Nancy McDonald was eighteen when they’d met, a year younger than Korovin, light and airy, like a newly built house waiting to be filled with furniture. She was not as slender as the two girls Korovin had dated in Russia, but she laughed a lot, often at herself, and she didn’t use makeup, didn’t attempt to look any prettier. She had long strawberry-blonde hair, so shiny and fragrant after each wash, Korovin found himself fantasizing about making love to her hair every night until he’d finally mustered the courage and snuck into her bedroom. He might’ve initiated sex, but Nancy had been the one to propose marriage, five months into the relationship, so he could stay in the country.

She had a miscarriage two weeks before the wedding, and another one half a year after, so when she got pregnant again, years later, they didn’t have sex during the first trimester, that is Korovin wasn’t allowed to penetrate her, but did anything else she dared him to do. He thought they’d been happy and that they would go on being happy. While she was pregnant, they purchased their first home in Manassas and Korovin repainted the walls, tiled the bathroom floors and the foyer, added on a porch.

The delivery was long and complicated. Her water broke prematurely, her cervix wouldn’t dilate. She had been in labor for thirty-seven hours, engorged with pain because the epidural had proven useless. Korovin stood next to the bed, his insides churning. He could do nothing to help her, except to let her squeeze his hand—hard, harder—until his flesh grew numb. After it was all over, after the doctor had pulled the baby out with a pair of metal forceps, Nancy tried to stand up and walk to the bathroom but fell on the floor, crippled with pain—her pelvic bone had been broken.

◆

In the kitchen, Korovin drowned a bowlful of Cheerios in 2% milk. He’d Americanized, his mother had said. He indulged in reality TV and no longer ate eggs for breakfast or drank whole milk. He also preferred burgers to beef-stroganoff, beer to vodka. He’d stopped drinking hard liquor after that last fight he’d had with Nancy, before she left him for the psychiatrist, whom Korovin had proclaimed an Auschwitz doctor.

“He’s using our son as a guinea pig, to conduct his bullshit experiments and write his bullshit papers on autism!” Korovin had screamed.

“And you’re using our son as an excuse to drink and feel like a martyr, doing nothing!” she screamed back.

“Like what?!”

“Like talking to someone other than your mother. Like going on vacations. Like having sex. It isn’t my fault. It isn’t your fault. It’s no one’s fault. Live with it.”

“I don’t want to live with it. I’m not like your parents. I can’t go on pretending that everything is O.K. Nothing is real to them. They still think Daniel will outgrow his disability.”

“You’re pathetic,” she said.

Korovin knocked her favorite vase off the shelf. His fist shook; he was that close to hitting her. In the doorway, he saw Daniel making disturbed monkey faces at them, emitting those guttural primordial sounds. Nancy left the next day, and Korovin kept finding pieces of Murano glass on the living-room floor months afterward.

Korovin chewed his cereal, listening to the sound of the coffeemaker spurting steamed water. The cat poked its head through the basement doorway, and Korovin hurled his slipper at the animal. He heard the cat hop over the child’s gate and thump down the steps. The house remained baby-proofed—safety cabinet locks, padded table corners—even though Daniel was seven. He still slept in pull-ups and didn’t say an intelligible word. For the first two years, Daniel had made almost no sounds—he didn’t cry or coo. When they talked to him, he wouldn’t look at them, but rolled his head from side to side, as if trying to get rid of ear noise or make them shut up. Korovin stopped speaking Russian to his son because Nancy suggested it might confuse him even worse. By the time Daniel was three, he bit children on playgrounds and poured sand on their heads; he could spin circles for thirty minutes, but couldn’t sit longer than thirty seconds, unless in front of a TV, watching the same episode of Thomas the Tank Engine.

Korovin and Nancy were searching for answers. They had tried everything from ABA (applied behavioral analyses), to biomedical intervention (heavy-metal detoxification, MB 12 shots, GFCF diets), to listening therapy based on the Tomatis Method, to Hyperbaric Oxygen therapy, to acupuncture, to homeopathy, to horses. Korovin spent long hours behind his computer, surfing the net, scouring websites for any new information on autism. He read a few recommended books —Temple Grandin’s Thinking in Pictures, Jenny McCarthy’s Treating Autism, and The Natural Guide to Autism—but found them somewhat incoherent and too depressing.He and Nancy joined a support group, where they met more aggrieved but active parents of special-needs children. Somehow talking to those parents had made the reality that much harder and also permanent. No one knew what caused autism, despite some speculations about certain vaccines, but there was no cure and no prevention—it was a spectrum disorder not detectable through amniocentesis and one more common in boys than girls. Somehow, it reminded Korovin of his native country—a beautifully conceived place with a severe developmental disorder, which had left it permanently handicapped.

For a while after Daniel’s birth, Korovin had not been able to sleep or make love to his wife. At first, he worried about her just-healed, yet fragile, pelvis, the weight of his body against hers, then about all the emptiness inside her, about touching that part of her where life used to grow. He had difficulty letting go. He began to worry about getting her pregnant again accidentally, about his child never maturing, never becoming an independent human being, an adult.

At his mother’s request, Korovin’s relatives in Russia had walked through eleven churches, burning candles and praying for his son, substituting a Russian name Danilo for Daniel so as not to confuse the priests. His mother had also mailed Daniel’s picture to one of her friends in Moscow, who took it to a manual healer, who, in turn, advised them to baptize the child as soon as possible and give him a new Christian name. When Korovin had brushed the idea by Nancy, who was an atheist but whose family was Episcopalian, she endowed him with a look of both misery and pity, convinced he’d lost his mind.

◆

Korovin drank his coffee out of a tall mug that said “I Love You, Daddy” in goofy mismatched letters imitating a child’s handwriting. By now, Korovin knew that his son would probably never learn how to write anything except his name. On the other side of the mug was Daniel’s baby picture. He was a gentle boy with azure eyes and corn-silk bangs, soft sensuous mouth. He looked healthy and absolutely normal. When they ate out, waitresses addressed his son as they would any child his age—with cute smiles and syrupy voices—before they could notice that Daniel paid no mind to them or anyone else in the restaurant.

Korovin scooped some cat food into a dirty bowl and set it out on the basement steps. He also lit an apple-scented candle in the kitchen to camouflage the stink, not that Nancy cared how his house looked or smelled. Her new house was the Kremlin compared to Korovin’s ranch-style shack. He thought how helpless one must feel surrounded by all that space, rooms of unused furniture. He wondered how many antidepressants she was taking. Was her husband prescribing them? Mixing them? Were they doing it together? Korovin’s medicine cabinet brimmed with an over-the-counter sleeping meds and the herb pouches his mother encouraged him to put under his pillow. She’d also given him a night balm to rub behind his ears and under his belly button, which (to his shame!) he’d actually tried.

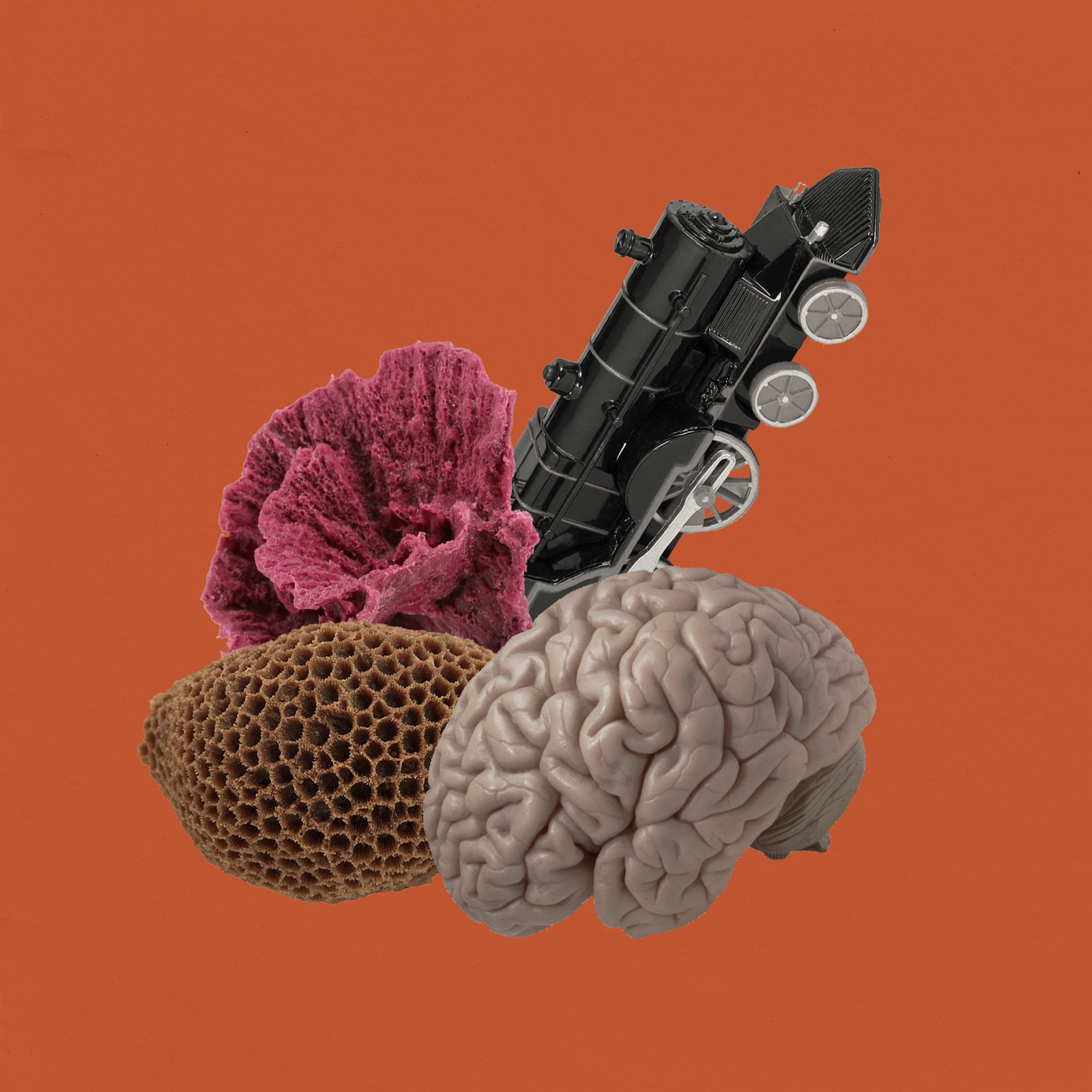

A few nights ago, having drugged himself to sleep, Korovin had dreamed of giving birth to a rock baby, pushing it out into the world through his bellybutton. He picked up his baby, all covered in blood and spumy mucus, and cradled it to his chest. He patted the hard, petrous shoulders and back, the tiny knobs of seashells in place of vertebrae. He felt a gurgle of sounds released in the air, a mossy dampness of the baby’s breath on his skin. He touched the baby’s perfect, carved-out hand and his mother-of-pearl fingernails, the tracery of crystal-speckled veins. And then he kissed its head alive with algae hairs. Inside the translucent, carapace-like skull, Korovin saw a pink coral of a brain unfolding under his touch. Korovin wept, bewildered by his child’s beauty that only he could see.

◆

Upon Nancy’s and Daniel’s arrival, Korovin was still in his pajama bottoms and a coffee-stained T-shirt. But he’d washed his face, brushed his teeth, and combed his hair, which was mostly gray now. He didn’t shave, however, despite Nancy’s aversion to beards.

“My God, it stinks in here,” she said as soon as they entered, Daniel’s hand in hers. He’d grown taller, his hair cropped and prickly, straw-like.

“Hey, buddy,” Korovin said. “Hug.” He opened his arms—wide, wider—exposing a large hole under his left armpit. Daniel wrapped himself around Korovin, and for a moment Korovin felt known, missed.

Nancy dragged in Daniel’s suitcase and the diaper bag, abandoning both in the middle of the foyer. She dug in her purse. She looked nothing like the girl Korovin had married. She’d lost twenty pounds and injected her face with Botox, so now it remained expressionless at all times. Her hair was still long but dyed reddish-brown, which reminded Korovin of faux mink fur. She wore makeup and skinny clothes. She was no longer a spacious house, but a tight, cluttered room he had no way of entering. Somewhere in that room, behind a dusty chest of drawers and an armoire, there were photos of them together, smiling, touching, making love.

“You really should get rid of that cat,” she said, handing him an envelope. “You look like you need a bath, too. Have you been drinking? Because if you’ve been drinking—”

“I haven’t been drinking,” Korovin said. He switched his eyes to Daniel, who was examining an old light-fixture, a forgery of mica and Tiffany-style glass—triangles within triangles soldered together with uneven black seams.

“What’s in the envelope?” Korovin asked.

“Money. In case you need some extra. Don’t want you to feel pressured.”

“Was this your idea or your husband’s?” Korovin made an effort not to raise his voice.

“Relax. Why can’t you appreciate a nice gesture?” Her face betrayed the pleasure she took in humiliating him, if only occasionally. When did they get so sad, so bitter?

Daniel tugged at Korovin’s hand, pulling him into the living room, toward the TV. Korovin gave his ex-wife a hard stare. They used to laugh at things, small things, like when he asked her after sex, “You O.K.? Did I make you good?” Now, they were two ships or trains who needed traffic controllers to help them navigate through the shared spaces.

“I don’t want your money. I’m capable of caring for my own son.” Korovin heard the TV come on and a few restless, glottal sounds from Daniel as he tried to change channels.

“Don’t give him any sweets or juices,” she said.

“What about acai? Did you read that article I sent you?”

“Yes, but I don’t believe it to be as miraculous as they say it is. Might cause allergies, too.”

Korovin knew he had no say in medical matters. He worked for an immigration lawyer translating documents from Russian into English and vice versa while Nancy was a nurse, employed by her psychiatrist husband, who owned his bullshit practice. Korovin’s opinion was inadequate against their professional success.

“I have to go now,” she said. “My parents are your emergency contact.”

“Have fun. Unlimited. Food. Sex.” He hated he’d said that, but she pretended not to notice.

“Bye, honeybun,” she called after Daniel and, placing the envelope on top of the suitcase, stepped out the door. It could be hours before Daniel would discover that she’d left.

Korovin picked up the envelope and counted the money—six hundred dollars, two hundred a day. She was paying Korovin to babysit his own son and also not to feel guilty about enjoying herself on the cruise. Korovin’s heart blistered with anger.

In the living room, Daniel had all the DVDs open and scattered across the floor. Korovin squatted next to his son and chose one of the Thomas the Tank Engine disks to insert into the player. “Is this one O.K.?” he asked. “Do you want to watch it? Or do you want to color instead?” Korovin reached under the coffee table and produced a thick notepad and a blue plastic box of crayons gathered at various restaurants. Both the pad and the box felt sticky and stunk like cat piss. Before Korovin had the time to get up and find a rag, Daniel pulled the box away from him and dumped all the crayons on the carpeted floor.

“No, no, Daniel.” Korovin shook his head. “Look at this mess.”

But Daniel paid no mind to Korovin’s remarks, the boy’s eyes on the lonely suitcase in the middle of the foyer. He leapt to his feet and hopped all the way to the entrance door, only to discover that it was locked and that the foyer was empty. Korovin watched his child stall by the piece of useless luggage, his face contorting into a grimace. How much Daniel understood the world around him or his own presence in that world was an ongoing mystery to Korovin. Sometimes, he wished he could sneak inside the boy’s head and rearrange things, connect the drawbridges.

“Ma-a-aw,” Daniel called and then repeated in the same low, nasal voice “Ma-a-aw.” He sounded like a calf hungry for the tit.

“She’ll be back, buddy. Soon. I promise. It’s just you and me now, O.K.?” Korovin hollered from the living room. He stood up, ignoring a huddle of crayons in a pool of multi-colored dust, and walked to his son. Daniel was doing that thing with his head again, shaking it as hard as he could, as if something inside there irritated the wits out of him. He began to spin, hands out, and Korovin attempted to catch him and root him in place. His son would stop for a brief moment, giving Korovin a foggy stare, and then resume spinning. Korovin closed his arms around the boy in a kind, yet forced, embrace. But Daniel squirmed free and took off running through the house. On the floor, next to the suitcase, Korovin noticed a spray of yellow droplets.

Korovin had always been a person of impulses—right or wrong, only time could tell—but from the McDonalds he’d also learned not to panic or adhere to hasty decisions. First, Korovin stowed away the crayons and cleaned the rug while Daniel rode with Thomas, Lady, and other engines through the Island of Sodor on TV. Inspecting the rest of the living room, Korovin found multiple offences, fresh and old ones, dried up in gooey rivulets on the couch, the chairs, and the entertainment center. Korovin washed and scrubbed them off the best he could.

From the basement, he exhumed a pet carrier and set it on the kitchen table. He also pealed open a can of food, deliberately slow, letting the cat, if it was in the house, recognize the familiar sound. He placed the can by the basement door while waiting at the table, the money envelope in front of him. The animal approached the food, slurping the juices, taking hungry bites. Korovin rose from the table and tiptoed around, looming over the cat like a thunder cloud over a mountain. The cat must’ve been too hungry or too lazy to notice, so when Korovin grabbed it by the scruff, it didn’t even act surprised or attempt to scram away. Korovin hefted the animal and forced it inside the carrier and shut the lid, then called his mother.

“I want to baptize him,” he said, repeating the words in Russian.

“Who? Daniel?” she answered, also in Russian. Her voice sounded unrushed, sleepy.

“Yes. But we have to do it today. Didn’t you say there’s a new Russian church close to your house?”

“Greek. Greek Orthodox. On Viscoe Road. But they baptize on Sundays.”

“Will you go talk to them? Now? We can be there in less than an hour. I’ll pay cash. Five hundred.”

The cat began to mew, but Korovin ignored it.

“What’s the rush?”

“No rush. I’ve been thinking about what you said. A new name, a new beginning. Maybe it’ll help him.”

“Does Nancy know? You don’t want to start anything new by lying to your son’s mother. Even though I’ve never loved her,” she added.

“No, not lying. Will you go there? Call me if there’s a problem. I’m leaving right now, but I have to make a quick stop.”

◆

Daniel loved riding in cars, so it took no time to persuade him to trade Korovin’s piss-saturated living room for the clean dark-blue cushions of the back seat. The cat occupied the seat next to the driver’s. It made no sounds but peered humbly at Korovin through the metal grids. The Big Lick vet opened early, but the parking lot was vacant, except for one car. Korovin hesitated for a few minutes before getting out. He took a hundred-dollar bill from the envelope, rolled it and pushed it between the grids. He was walking fast, his eyes on the pavement. The day was warm, gray and windless, and Korovin was sweating inside his jacket. As soon as he reached the door, he placed the carrier down on a paw-shaped mat and hurried back to the car. Daniel was crumbling rice chips he’d discovered in the pocket of his diaper bag. He gave Korovin a vague, misplaced look.

The Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church smelled of yeast and melted wax, but otherwise didn’t resemble a Russian church. It had pews with bibles and books of hymns tucked in wooden pockets and stained-glass windows with biblical images livened by daylight. There were no hand-painted frescoes on the walls or gilded icons with beautiful suffering faces of saints, and no people, except for Korovin’s mother dressed in white and clutching something small in her fist. She was still the same petite yellow-skinned woman who’d once tried to jump out of the window to prove some dumb thing to Korovin’s father.

In the upper left corner of the church, Korovin noted a large square brass stand, where hundreds of red-glass candleholders glowed with tiny flames. His mother had once compared them to human souls, and it gave Korovin an eerie, uncomfortable feeling. The church was too bare and too spacious, its modern altar unadorned with the work of goldsmiths.

“I talked to Father Sergei, and he agreed to baptize Daniel,” his mother said. “Did you bring the money?”

Korovin nodded, pulling the envelope out of the diaper bag.

“Father Sergei said to put it in that box.” She gestured toward a cardboard receptacle. “He went to prepare. I’ll be Daniel’s godmother since there’s no one else. You O.K.?”

It was a simple question, but Korovin didn’t know how to answer it. O.K. was just as complicated as love or pain. All three had infinite meanings, multiple connotations. He walked to the receptacle and pushed the money through the slot.

“Here. I’ve had this for a long time.” His mother followed him, opening a square velvet box, and Korovin glimpsed a flat, leaf-like cross nestled in the folds of white silk. “Have you thought about a new name for him?” She avoided addressing Daniel directly, as well as touching him. “Maybe Peter? Like the apostle?”

Korovin shrugged and switched his eyes at Daniel, who was pushing Gordon and Daisy along a pew. His son exhibited no signs of distress or discomfort.

Father Sergei wore a floor-length white cassock with blue and golden embroidery and a matching bulbous hat. Half of his face was hidden under his thick mossy beard, but the rest was wide and smooth, baby-like. On his neck hung a pectoral cross he kept touching as though to assure himself that it was still there. He spoke in a hushed heavily-accented voice, dropping words into his beard, and Korovin imagined them spawning there like mushrooms.

The priest brought out a large brass basin filled with water and set it on a table. He lit three tall altar candles, opened a chaffed leather-bound bible, and invited everyone to gather in a circle. At first, Daniel seemed to have understood what Father Sergei asked him to do—leave the trains on a pew and take one of the burning candles in his hands. Korovin was allowed to help his son hold the candle, guiding him around the basin as Father Sergei chanted passages out of the Bible. But after the first circle, Daniel refused to continue. He dropped the candle on the floor and it almost caught the hem of the priest’s cassock on fire. Both Korovin and his mother helped extinguish the flames, ladling water out of the basin, and Father Sergei proceeded with the ceremony. But Daniel wouldn’t listen and wouldn’t budge. He had to get to his trains. Korovin attempted to hold him in place by force, reiterating, “It’s almost over. Just a little bit longer, buddy,” but to no avail. The boy kept fighting his father with all his might, kicking and tearing his way out of Korovin’s arms. He began to cry, then wail, bear-like, and Korovin’s heart froze with pity.

“Don’t let go,” Korovin’s mother said, and Korovin locked his arms around his son and tried to pick him up. Daniel was heavy but limber, wiggling, slipping from Korovin’s determined clutch. He heard the boy grunt, and then he went limp, sagging to the floor.

“Sometimes you have to fight hard,” Father Sergei said. “But you should never doubt your strength. The Devil seeks the weak.”

“My son is autistic, and he just shit his pants,” Korovin said and lifted the boy to his chest. He stepped down from the platform, reaching for the diaper bag.

◆

In the bathroom, Korovin undressed his son from the waist down and began wiping him with wetted paper towels. Daniel was meek and obedient as though apologizing to Korovin for everything that had gone wrong in their lives. They were both silent. Daniel raised his head and Korovin glanced in the mirror, a soggy, smelly towel in his hand. In the reflection, he held his son’s gaze, but just for a moment, long enough to note how much Daniel resembled Korovin and Nancy at the same time. He remembered how the night before Nancy’s water broke, he’d watched his wife undress. In the dark, her belly was like the moon, huge, glowing. He got up from the bed and walked to her—close, closer—her taut flesh against his, their child safe between them. Korovin remembered being overwhelmed with a sense of oneness, wholeness he must’ve known once before. They were a unit, a cell, a man-woman sharing a womb, growing a life.

Korovin washed his hands and then his son’s and, getting the trains out of his pockets, gave them back to Daniel.

Korovin’s mother waited for them outside, smoking.

“Need a ride?” he asked.

She shook her head and dropped the cigarette on the ground. “Faster to walk.”

He unlocked the car, letting Daniel crawl inside.

“Sorry,” she said, and then added, “There’s this prophet in Russia—”

Korovin scowled, but remained silent.

“You know I love him, right?” she asked.

He nodded and slid behind the wheel. He dropped the bag on the seat next to the driver’s and turned on the engine. She blew kisses to Daniel, but he had no idea what they were, his toy trains speeding across Korovin’s shoulders.

The day was overcast, clouds roofing the city, instilling a sense of calm in Korovin, odd comfort. A few drops of rain dappled the windshield and dried off just as quickly. Korovin drove, while Daniel leaned against the seat, gazing out the window, the engines capsized on his lap. Korovin asked the boy if he was hungry and suggested stopping by Thelma’s Chicken and Waffles, where they served breakfast all day long. They could share a broccoli omelet with soy milk and soy cheese and gluten-free waffles or pancakes, and real maple syrup. And if he wanted, Korovin said, they could try Thelma’s chicken too, they could even order it to go and save it for dinner. And when they would arrive at the house, Korovin would unload the car and retrieve his old carpentry tools from the piss-reeking basement. They would first assemble a train village and a depot and then go on building a railroad, sturdy elaborate tracks all the way to Sodor, and he and Daniel would ride many trains, as many as they could, for hours, all night long—for as long as it took to get there.