I took the train back to the city where I live, sitting in the quiet car beside the university administrator. She concentrated on a book; I stared at the trees as they slewed past. The professor who had led our campus visit, our reconnaissance mission, as we called it, went home alone in a chauffeured car the university had hired for him. It must have cost a fortune. I was glad the professor wasn’t on the train with us. He was my dissertation advisor, and I didn’t know how to tell him I no longer wanted him to serve on my committee. He’ll be happy to free himself from his commitment to me, I thought. He’s a famous academic, famous among academics, I thought, and probably considers his service on my committee a distraction from his real work, his scholarship, as well as the work of heading this task force that has been convened to reconsider how the arts are taught and practiced on our campus. Task and force are ugly words, ugly on their own and doubly ugly when conjoined, words far from the ideal nature of research in the arts, which should be playful and free, I thought, but many artists do see their work as a task, many of the most famous masters see it that way, and maybe that’s the right way to see it, not as a calling, but as a task one masters; though the word master, too, I thought, is ugly beyond words.

I was relieved to be in the quiet car, where the administrator and I weren’t allowed to talk, although under other circumstances we’d have spent the trip recounting the self-important speeches we’d been subjected to during our reconnaissance mission. Instead, I silently rehearsed what I might say to the professor, my advisor, to extricate myself from his oversight. He hadn’t been a terrible advisor. He was available when I needed him, but never needled me about deadlines. He was playful and inventive when I brought my ideas to him, suggesting avenues of research I never would have discovered on my own. In some ways, I thought, he has been a dream advisor. And a letter of recommendation from a professor as famous as he is could prove crucial in my search for a teaching position somewhere, the academic job market being an absolute disaster, worse every year, especially in the humanities. What he’d said to me in the museum—no one else had heard it. No one would know he’d said it, if I were to keep quiet. It had meant nothing to him, nothing at all. Why should I make trouble for myself?

The purpose of our reconnaissance mission was to study the situation of the arts at this other university, because our embarrassingly wealthy university, where the making of art has been exiled outside the curriculum and, though patronized with a smile, kept separate from those studies that lead to a degree, is jealous of the world-famous arts programs at this other embarrassingly wealthy university. After months of working with the task force, I’d become accustomed to ugly phrases like arts practice, phrases invented by gallerists to talk about something artists ideally undertake in private. By arts practice and the like they gesture toward something that at its best is unpredictable, something that can’t be planned on or prepared for, something precisely impractical, an undertaking that’s better not spoken of at all, a task that’s not in need of phrases to bandy about in fatuous personal statements and money-grubbing gallery prattle. But constant use of those ugly phrases had made them practically invisible to me.

Although we had allotted only one day to the gathering of intelligence at this other university, our agenda had been ambitious. We would consult the arts provost, the woman who oversaw the construction of new arts spaces, an art historian, painters, the dean of the school of architecture, a filmmaker, some actors, the chief arts librarian, a dance studies graduate student, and the director of the program for sacred music. Our schedule was crammed with meetings, leaving only one hour during the day to use as we wished. My advisor suggested that he and I might visit the school’s art museum. Flattered that he wished to spend his one free hour with me, I accepted immediately. As the man’s teaching assistant, I’d helped him prepare a course on early modern travel, an evasive substitution for colonialism, I thought. Pirates is what the undergraduates had taken to calling the course, never in earshot of my advisor. My advisor preferred the word travel because he thought the word colonialism would place a student in a particular relation to the material in advance of their processing it, whereas the word travel would leave them open to other understandings of the exchanges between the European travelers and those they encountered, I thought he thought, exchanges that were always exploitative and usually violent, always in the end violent, as my advisor highlighted throughout the semester; still, I thought, evasive. At the time of our reconnaissance mission, this art museum had on exhibit some of the watercolors John White made during his expeditions to the Americas in the sixteenth century, watercolors we’d studied in the course on travel, or colonialism, or pirates. Most of these paintings depicted people, wildlife, and military fortifications in what was, for White, the New World, but White had paired these with fanciful paintings he’d made of some of the earliest inhabitants of Great Britain, the Picts. I was excited to see these pictures. Among the many European depictions of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, almost nothing on their level exists in the art of his period. But I was anxious about spending time alone with my advisor. I was desperate for his approval. And I was uncomfortable with his repeated inquiries about my sex life. He was endlessly curious about cruising and clubbing, what he called gay sexual culture, a curiosity that to his mind, I thought, was evidence of his unimpeachable attitude toward this so-called gay sexual culture, he had been friends with Foucault, after all, and I encouraged his curiosity, I admit, since I could see he was genuinely interested, and feeding him stories of sexual encounters, stories made palatable for him as well as for me by stripping them of their most interesting or saddest details, seemed like one way to secure his approval.

The enthusiasm I showed during our lunch meeting was so unconsciously performed that its hollowness was barely perceptible even to myself. But academic talk is painful to listen to, more painful than it is to read, especially when the academic speaks without notes, from the heart, so to speak, because academics live most of their lives in solitude, absorbing information, and the excitement they feel when they have an opportunity to expose to a live audience this information they have absorbed at great personal cost, as they see it, this excitement makes them ridiculous, they can’t wait to say everything they know, but since there isn’t enough time, they can only reveal a fraction of the numbing trivia they’ve compiled, most of what they know will go with them to the grave or survive them for a few decades in footnotes, and in these rare extemporaneous moments before a live audience the excitement they feel makes what they manage to say frantic and oppressive, they use ridiculous adjectives and ridiculous superlatives, so in attempting to communicate the importance of their cherished topic they disfigure what they know. It was painful to watch them perform while we sat at lunch, waiting for them to pause before taking a careful bite of food. These academics and administrators had no stake in our task force mission, apart from the disinterested love of the arts they professed. Why should they care how the arts are practiced on some other campus?

The assembled speakers displayed their enthusiasms and skepticisms in turn, each waiting politely for another to finish before taking the stage. The dancer, a graduate student like myself, was the last to speak, his face flushed with embarrassment or passion. There’s no point engaging in the arts as a hobby, he said, if a person doesn’t practice art at the highest level then it’s not art at all, there’s no reason for universities to peddle arts courses to future captains of industry, if it’s not at the highest level it’s not art at all, it’s wrong to read Death in Venice with these students or teach them movement, it’s not a service to them to feed them a spoonful of art before they go on to the pursuit of money and power, you might as well teach them to repair toilets, except it’s worse than teaching them something useful like how to repair toilets, something they can see the value of, it’s worse than that to throw art away on them, to expose art to their derision or indifference, he said. He had waited while the others spoke, all respected in their fields, all relatively secure and comfortable, before he offered his opinion, contrary to the others, that the world doesn’t need another art school selling junk master’s degrees, because there were already too many art schools, taking money from student-artists and providing them with educations that don’t enable them to make a living or repay their loans, his voice caught on the last word, too many art schools condemning student-artists to poverty as they struggle to repay their loans while they also struggle to practice their art at the highest level, or, as most do, eventually, surrender their art to dedicate themselves to repaying their loans, loans that forever frustrate their desire to make art at the highest level, art-murdering loans, he said, the last thing the world needs is another art school producing master after master after master, a distinction these arts schools make meaningless, schools staffed with art professors and managed by bureaucrats, those bureaucrats being the very people who once read Death in Venice only to seek afterwards a degree in business or administration, they sit in their offices collecting money from student-artists and in the process prevent these student-artists from making art at the highest level, they’re not art schools, they’re art graveyards.

After this lunch, my advisor went around the room, shaking hands. I locked eyes with the dancer, who was returning his notebook to his backpack. I wished he’d come talk to me, but I was too shy to approach him. My advisor collected me and we walked to the art museum, a large rectangular structure built of glass, steel, concrete, and, on the interior, white oak. The placement of its windows and skylights floods the building all day long with indirect natural light. When we were out of earshot, my advisor fixed me in his sly gaze and asked what I made of the lunch meeting. He’d seen me scribbling furiously, since it was my task to record all we saw and heard, I’m embarrassed by how seriously I took my task, straining to catch every word, while he sat in thoughtful silence, conscious that I was taking notes. He wanted me to address the dancer’s statement, surely, because he guessed that I was attracted to the dancer, or because the dancer’s words spoke to the exploitation of graduate students I too experience but never discuss, I was a student at a university with an unfathomably large endowment, employed as a teaching assistant, a job that consisted mostly of shielding the generously-paid professors from interactions with the generously-paying undergraduates, leaving little time for my own research, I led discussion groups, I graded papers, and in return I was paid a paltry stipend, not enough to live on, all the considerable time and energy I put into teaching I considered an investment in a future that might never materialize, though I couldn’t admit this precarity to myself honestly enough to plan accordingly, anyway, I thought, the dancer’s were the only comments that displayed real intelligence, but I chose not to talk about the dancer, I talked instead about the director of the institute for sacred music, who had expressed an opinion that the education of artists had become overly academic, resulting in a narrowing sense of the possibilities of what art can be. I laughed at his concern, nervously, looking for my advisor’s approval, I laughed at the idea that artists need to be protected from ideas. I pictured his students laboring over their loud, ugly pipe organs. At this point we entered the museum, and my advisor guided me to the room that housed John White’s watercolors.

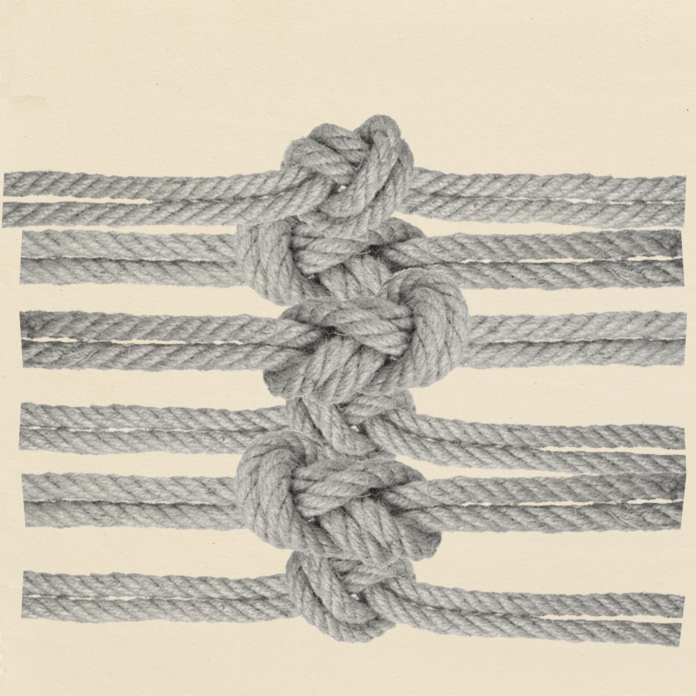

The security guard stood taller when we entered the empty room, and I wondered if she was ordered to stand at attention, like a soldier, it’s the sort of thing you’d expect a manager to do, to monitor her and document how often she slouches and yawns during a shift, making her job contingent on an appearance of alertness. These guards are paid very little to protect priceless treasures, and surely they’re not trained to handle a serious threat to the artworks, an armed thief or armed vandal, and if they save a big painting it’s not as if they get to take home a little one. This guard probably knows as much about these watercolors as anyone, maybe not about the circumstances of their making, but about the paintings themselves, the pigment on paper, few people can have been in a better position to study them. My advisor knew a great deal about these watercolors, he and I had talked about them in his office as he drew up the syllabus for his course, trying out words like archive and commodity, and I’d watched him discuss these watercolors with delicacy during lecture a month before our reconnaissance mission. Although White was of the colonizers’ party, the travelers’ party, as my advisor’s course description would have it, the pirates’ party, according to the undergraduates, and although White’s access to the world of these people must have been slight, however long he spent watching them or speaking with them through an interpreter, the paintings suggest he was an acute observer of what was before his eyes, wildlife and people and the buildings and tools and clothing, though we can’t know for certain why he gave them such careful attention, whether it was to fulfill the task imposed on him by the entrepreneurs who funded the expedition, or out of curiosity, or a sense of his calling as an artist, the tangle of motives is impossible to untangle, his use of the same techniques to portray an Algonquian woman and a man-of-war and a military fort need not mean that he formed a conscious relation among them, though perhaps the force of technique is enough, perhaps looking at them closely as he dipped his squirrel-hair brush into the crushed gold he had mixed with honey in a mussel shell brought them all into the halo of his concern, and perhaps he saw them all as equally valuable painting subjects, more valuable painting subjects than his fellow English planters, who appear nowhere in these paintings, who knows what he thought as he created these watercolors, I thought. The beauty of these paintings astonished me, especially the painting of the man-of-war. A diaphanous crescent flaunting a ribbed pink ridge on top and a mass of blue tentacles below, it looks like some kind of jellyfish, but it isn’t a jellyfish, it’s not related to jellyfish, in fact it’s not a single organism, it’s what biologists call a colony, composed of smaller animals, genetically identical, attached to the bladder. In White’s watercolor, the translucent bladder is threaded with blue veins and seems to levitate against the background, like a canoe made of flesh bearing a crown and trailing a necklace of tentacles. White himself seems to have been bewildered that this floating jewel should be an animal, and so he wrote on this painting: this is a living fish. White created this painting and others while his shipmates schemed and stole and murdered, I thought, and maybe this attention gave him a different relation to these lives than the conmen and bastards and murderers he sailed with. Or was he only carrying out his masters’ wishes, documenting commodities and future colonial subjects, performing this task that would help the English turn a profit on the colony, preparing the way for the application of force that decimated the indigenous population and replaced them with English colonists?

We now stood in front of a painting of a Pict, a naked woman with curly blonde hair that reached below her waist. We had spoken very little since entering the museum. But we were moving together, looking at the same watercolor for a few minutes, then stepping in tandem to the next. The Pict held a long spear, clasped tenderly in one hand, forefinger extended, not the way you’d hold a spear if you were about to use it, her other hand empty and relaxed, the back of her wrist placed against her hip. She was naked except for a black rope necklace and a black rope belt and a sword that hung from her waist, and she seemed unashamed of her nudity, proud of it even, her pale skin covered in colorful tattoos, even her breasts and her pubic mound, these tattoos are the first thing one notices, various flowers in various hues, like a wallpaper applied to her flesh, laid out symmetrically, the left half mirroring the right. As we stood in front of this painting, as I tried to call to mind the things he had said about this painting during lecture so that I could repeat them to him now and prove how well I had listened, he leaned close and whispered in my ear, in a hoarse voice, “Look at her cunt!”

I said nothing in response. The comment was uncharacteristic of the man I’d known in public settings, who was always courteous, careful, politic. John White’s picture does not, to my mind, merit erotic interest. How had it called from him that low, sultry whisper, and that definite emphasis on the final word? A definite emphasis on the final word, a word I avoid saying, though I know people who do say it, because they want to reclaim the word through use, like the word fag, which I use, among friends, to refer to myself and my friends, or perhaps others say this word I don’t say because they like how it feels to say a forbidden word, who knows. Her vagina isn’t even visible in the painting; her legs are modestly closed. Was the sight of pubic hair enough to elicit a sexual response, or was the layer of arousal in his voice fake? Was this not an irresistible gush of desire, but a cool display of manhood, an attempt to connect with me by asserting a shared right to bodies with vaginas? What would the women he works with, his students and colleagues, think of what he said? He would never say such a thing to them, I thought. Or would he? And would they pardon his erotic interest in the watercolor, if that’s what it was? I didn’t think they would, I couldn’t imagine it. I’m overreacting, I thought, it’s nothing, and also, did I invite this comment by talking to him about my sex life, and also, his remark is reprehensible, it’s a betrayal of his responsibility toward me as his student, from anyone that remark would be disgraceful but from someone in his position it’s evil, and to whisper it in my ear in this museum, where I can’t respond properly, it’s revolting, and also, I thought, the straight men who are my classmates would think nothing of this, I’d heard disgraceful things from them too, shocked that men who chose to spend their lives in the study of literature could think of women in this way. I knew if I were a different kind of man this moment might be an opportunity to seal the relationship with my advisor and earn a glowing letter of recommendation, a form of currency, a letter that could lift me toward tenure somewhere and a financial security I’d never known, and if I were a woman this remark would never have been uttered, this path to his approval and friendship would never have opened to me, I might never have known that it exists. It was revolting and unjust, a disgrace for the university, for the profession, and I couldn’t respond properly, forget the museum, that’s not why I said nothing, I couldn’t respond with the scorn his comment deserved without endangering my career prospects, I thought, immediately reproaching myself for this unworthy consideration, but no, why should I blame myself, I hadn’t said the disgraceful thing, I hadn’t put myself in this position. I stood there, wordless, then moved to the next watercolor.

When I reached my shabby apartment, shared with four strangers, none of whom were home, it was past noon. I had a few hours before the next meeting of the task force. I typed up my notes from our reconnaissance mission and sent them to the administrator and my advisor, then showered. We were to meet over dinner at a restaurant near campus, where a single meal costs a tenth or more of my monthly stipend, but the task force would pay for everything. I loved eating these task force meals, which always involved freely swilling expensive wine, so that our discussions deteriorated but became more lively as they went on, but I also resented the money lavished on these gatherings, considering how stingy the university is with our graduate student stipends. After my shower, I dressed in a state of dread. I couldn’t stomach the idea of sitting silently at the end of the table, scribbling down what others said about arts practice. Would I tell him I no longer wished him to serve on my committee, and would I tell him why? It would be the easiest thing in the world to invent an excuse not to go to this dinner. But I showered, then selected an outfit I hoped would be suitable. My advisor, I imagined, would wear a fine suit, no tie, and one of those white shirts he’d bought in Italy for an exorbitant sum, he had told me the price once but I can’t remember it now, only that I couldn’t tell the shirt apart from any other white shirt. It had seemed incredible to me at the time that he would boast about his expensive shirt to me, his underpaid graduate student, but I imagine that most of the pleasure that purchasing an expensive, bespoke shirt affords comes from telling people that you had purchased an expensive, bespoke shirt.

I decided not to talk to my advisor until I had decided what I was going to do. I didn’t want to compound my lie, for that’s what it was: my silence in the face of his monstrous behavior was a monstrous lie. Even as I marched toward the restaurant, I longed to make an excuse not to attend this dinner. I could text the administrator to explain my absence, or I could tell my advisor the truth, I could send him an email denouncing what he had said. Would he be chastened by such a message, or would he retaliate? Perhaps I should threaten to report his behavior to the university, I thought. But I didn’t skip this task force dinner. In fact, I arrived early.

The restaurant occupies a First Period house, its structure similar if not identical to the famous old jail in Barnstable. I had never set foot in the restaurant, but I had noticed its odd size and proportions, the door and windows gigantic in relation to the frame, or rather the reverse, the door and windows a normal size and the frame miniature, reminding one of a dollhouse. As my eyes adjusted to the dim interior, I told the restaurant’s host that I had come for the arts task force dinner and asked if any members of my party had arrived. This gatekeeper was a man in his fifties, dressed in a gray tweed suit. He looked me over with exaggerated indolence, then told me that I couldn’t enter the restaurant without a jacket. I waited for him to let me in on the joke; when the silence stretched out, I realized the restaurant really did have a jacket policy, something I thought existed only in movies. I asked if the restaurant kept handy a jacket I could borrow; he informed me with faultless politeness they did not. Even if I were wearing a jacket, he added, I was not suitably dressed. I took his disdain as confirmation that I shouldn’t have come, that I didn’t belong, but I persisted. Elitist slights, which this university offers unstintingly, fill me at the same moment with crippling shame and also with hot, proud anger. I told him I had been invited by the arts task force and must be admitted, despite the restaurant’s jacket policy. Anyway, I told him with genuine feeling, it’s outrageous to require diners to conform to a gendered dress code, this is obviously true though at the time I was moved to say it by necessity and embarrassment, your jacket policy is stupid, I said, unloading on him the scorn I couldn’t express to my advisor, but neither my argument nor my show of feeling had much effect. If I had thought he was merely doing his job, doing the stupid bidding of his stupid manager, I wouldn’t have been so angry, but I could tell there was glee tucked under his flat expression. He wanted to humiliate me, and I cooperated in my humiliation, threatening him with unspecified consequences for enforcing the stupid jacket policy. I had pulled out my phone to text my friend, the university administrator, when my advisor appeared, smiling, and shook my hand, and pulled me, with no resistance from the host, into the restaurant.

I had resolved not to speak to my advisor until I had reached a decision, but I found myself not only talking to him but speaking suddenly, nervously about John White, skirting close to the topic I very much hoped to avoid. It was natural enough I should speak of White, since we’d seen his watercolors only the day before, and I told him some jumbled version of my idea that White’s attention to his subjects, regarding them through the lens of art, distinguished him from his travel companions. This theory he immediately contradicted. Not only was White of the colonizers’ party, he said, he was made governor of Roanoke on a subsequent voyage, and he brought his family to live there, in order to help cement a permanent English presence in the New World. In fact, it was White’s granddaughter, Virginia Dare, who has the dubious distinction of being the first English child born in North America, he said. In White’s first visit to Virginia, the English burned a village because they suspected that one of the inhabitants had stolen a silver cup. Luckily, the inhabitants of this village had fled before the English torched their homes and crops, but who knows how many starved that winter when they returned to find their homes and crops in ashes. White was thoroughly implicated in the English violence, though this early colony was lost while White was home in England, where he sought support after an expedition he sent to exact revenge on the native people went spectacularly wrong. While he was absent, Roanoke vanished. White came back to Virginia to search for the lost colonists, his granddaughter among them, but he never did find them, nor was he able to discover what happened, nor do we know today what became of them.

The members of the task force began to arrive. The heavy wood table was too large for the dining room with its low ceiling, it was a minor miracle that everyone was able to squeeze in around that table, but no one minded, their happy voices mingled as they exchanged polite conversation. I sat at the far end, next to my friend, the administrator, who was rifling through her notes. She handed everyone a report detailing the information gathered during our reconnaissance mission. My advisor offered a rehearsed introduction, citing an Elizabethan handbook of the arts, mostly cribbed from an earlier Italian source, he said, neither of which I knew, in which the author refers to the delightful practice of painting, and then a little later refers to his seven years of painful practice, painful meaning painstaking of course, suggesting that a practice that requires great pains can be a delight, a delightful, painful practice, he said, then paused briefly to give his conclusion more weight, his question he said was how do we create space for our students to engage in delightful, painful arts practice? He yielded the floor to a circus of commentary, the food was served, the wine consumed. A sculptor obsessed with climate change was present at this dinner. At every meeting she would ask the assembled thinkers to consider the looming catastrophe, a warning the task force members dismissed, thinking the topic far from our mission as an arts task force, you could see it in their faces while she spoke, she’d lay out data about climate change gathered from the internet, interrupting the conversation about how we might foster the arts without unintentionally stifling them with oversight, and no one would respond to what she said, the flow of conversation would reissue where it had left off, inwardly they laughed at her theatrical warnings, I could see that they did, and now the sculptor put down her glass of red wine and admonished us that any new art spaces shouldn’t be located near the river, because we couldn’t predict what the river would look like in twenty years, fifty years, one hundred years, when the planet passed a hellish threshold from which there would be no return, damning us and our posterity to misery and extinction; that’s true, I thought, as the task force members debated instead whether the university should establish masters degree programs in arts practice, how these programs might be funded, and so on. The sculptor’s prophecies seemed a thousand times more reasonable than another proposal that cropped up, that the physical layout of arts spaces on campus ought to be designed to maximize interactions at the interstices, where artists from different disciplines could cross-pollinate, this concern for interstitial spaces had been greeted with serious interest, so that the word interstices was repeated several times at every meeting, like a prayer, again and again we returned to the topography of arts practice, what was needed was a horizontal distribution of the arts, not a vertical one in which a position of mastery would be retained, a horizontal distribution would be better, one that would that maximize the number of interstices and wouldn’t privilege one arts practice over another but would instead allow for overlap and transgression and adaptation and quotation, really the sculptor seemed like the only reasonable person in the room, her hysteria, for that’s what they all thought, I thought, her climate hysteria was the reasonable response to what awaits us, and our books, and the many paintings outside of the climate-controlled museum collections, paintings scattered around campus, not masterpieces, not priceless works, but old oil portraits of illustrious men, mostly, paintings displayed in the libraries and classrooms and dormitories, fusty portraits of fusty men silently surveying the student body, silently communicating what the university values. We should all be screaming, I thought.

The food disappeared, the fire was stoked by a server and the room began to feel too warm, it grew warmer the more we drank, until it was uncomfortably hot, my advisor took off his jacket, revealing that expensive white shirt of his, the administrator and I stopped taking notes, she was making instead a cartoon of the little dining room with its big personalities while I drew a map of the ideal configuration of the arts spaces on campus, horizontal, far from the river, inept drawings we showed each other to suppressed laughter. The room shrank and got hotter, everyone was quite drunk now, though maybe I was projecting my drunkenness onto them, I’d reached the familiar stage of inebriation where I desperately want to fuck someone or swoon to death, the worst thing in the world would be for this conversation to continue, but the fireside ritual showed no sign of stopping. The talk of interstices inspired my advisor, who untucked his priceless white shirt and unbuttoned it somewhat so I could make out the hair on his chest, he was inspired to recount a story from a symposium on the tango that he once attended. The most interesting presenters, he said, were a pair of women, one an academic and the other a dancer, the academic was seated in a chair on an empty stage and read an academic paper while the dancer moved around her, she was not dancing the tango but she and the academic were engaged in a kind of tango, the dancer’s movements were aleatory and bore no obvious relation to the text the academic recited, the academic was a thin birdlike woman wearing a gray wool dress he said and the dancer was a huge bull dyke, at the words bull dyke there was a titter of laughter from the drunken guests, perhaps they were uncomfortable but no one said anything, and here my advisor pushed the heavy table away from him somehow to get a little space and he stood up beside his chair, performing an imitation of the dancer’s random movements, dancing around the empty chair like a clown, I don’t remember a single thing the academic said he said, but I do remember that when she had finished reading a page she tore that page from her paper and handed it to the bull dyke, who ate the page, he tore a page from the report of our reconnaissance mission and crumpled it and stuffed it in his mouth though he didn’t actually eat it, he just chewed on it for a moment and then spat it out and tossed it in the fire, there was general laughter now, this was a spectacle that surprised the attendees of the symposium he said and there was a danger that the shock value of the performance would overwhelm its meaning, but he was interested in the circularity of the piece, the tango that was consumed, figuratively, by the seated academic’s art criticism, which was then consumed, literally, by the dancer, this ouroborous continued he said until the final word was read and the bull dyke ate the final page, every time he said the words bull dyke there was laughter, surely he had friends who referred to themselves with that term, otherwise he wouldn’t be so comfortable using it, and I sat in tense silence, waiting for him to use that other word, the one he had lustily whispered in my ear in the museum, I willed him to say it, I thought it again and again in my mind, hearing the definite emphasis he placed on the word, willing him to say it before the wine glasses could be filled once more, before he could eat another page of the arts task force report. Say it, I thought, though I said nothing myself. Say it.