Our empirical experience of death is the disappearance from the physical plane of living beings. Such is the fact of our experience from without, that we have by means of our five senses. But the disappearance as such is not confined to the domain of outward experience of the senses. It is experienced also in the domain of inner experience, in that of consciousness. There the images and representations disappear just as living beings do so for the experience of the senses. This is what we call “forgetting.”

◆

The girl was thirsty.

Her cheeks were hollow and her hair formed a knot on her neck, hair barely combed. A prehistoric voice came out: “Did you have water on this boat?”

They were hoarse, drawled words, for a question that carried in itself an obsessive refrain. It wasn’t a question in the past, it invaded the present and lodged itself in the future: water, water, water, the girl’s parched throat blazed up, multiplying in the throats of all. Nicola thought that food you could get, although it was difficult, but water was different and without it no one would survive.

“So is there water on your boat or not?”

Her white shoes were new and inadequate. The tips were covered with mud: a dark winter had been laid on that unseasonable summer.

“We can go together to look for some,” the child answered, pointing to the city. He had just set foot on the ground and hadn’t much desire to return to the boat.

“If there was any do you think I would have asked you?”

The crowd pushed forward and the sailors began to disembark. It was an instant, and against the flow, through an invisible opening, the girl managed to slip onto the boat. Water, thought Nicola, means many things: the salt water of the sea that had buried the world, the stagnant water of the cellar in Piazza San Filippo that had been useful for survival, the water like something dazzling that drove the girl to get on an unknown boat.

The sailor who had taken the silverware was not among the soldiers arriving on land. Probably he had lingered inside and wouldn’t be pleased to find an intruder. Nicola decided to turn back.

At first he saw no one. His relief increased when he saw her, slaking her thirst from the barrels on board. Water, water, water.

A cold shadow rested on the boy’s shoulder. Here he was, the man to whom he had handed over the silver in exchange for safety.

“I was good to you and you repay me by letting your aunt sneak on?”

The girl was frightened. The water she’d been gulping had ended up on her cloak and her hair, mussing it and curling it even more, while her deep, frightened eyes sought a way to flee.

“Is that how they teach you to behave? Like a thief?” The soldier advanced.

“Maybe in your parts that’s the custom. As for us, they teach us to risk our life to save others. I will die under one of your buildings or burned by one of your fires, and I will have died for a population of thieves.”

He stopped. “Because it’s clear that the Lord has punished you. He wouldn’t have struck down a people if that people hadn’t deserved it.”

The girl gained a space between the sailor’s body and the door, breathed in to get into her lungs as much air as possible, and took a run-up; but the man immobilized her, folding her arms behind her back.

“I brought you your nephew, I ferried him safe and sound, and you didn’t even say thank you.”

The girl looked at Nicola, uncomprehending.

“Thank you,” she entreated, trying to get free, but the soldier pushed one hand against her breast and squeezed it, then stuck the other under her skirt. His broad back covered her entire body, starting something for which there were no words. Fight, clash, battle are words that imply a confrontation between equals, and yet there was no equality in what happened. The girl tried to scream, the sailor took off his cap and used it to stop up her mouth, pushed her to the floor and began to move on top of her.

Three torpedoes and four cannons. During the crossing Nicola had reflected that the weapons on the small, heavy torpedo boat Morgana could kill them all, the people of Messina, those of Reggia. That thought helped him keep at bay a worse thought, about the most disturbing and dangerous weapon on board: that sailor’s gaze. The eyes most like his mother’s he’d ever seen.

“You stood there staring to learn how it’s done?” the soldier said to him with a sneer, as he left. Nicola remained petrified, incapable of responding. His voice was hidden in the depths of his throat, disappeared, vanished.

The girl had stood up, and had a vacant expression. She no longer seemed of this Earth. Her hair was crushed against her neck. She passed by him, and she, too, left, without saying a word.

◆

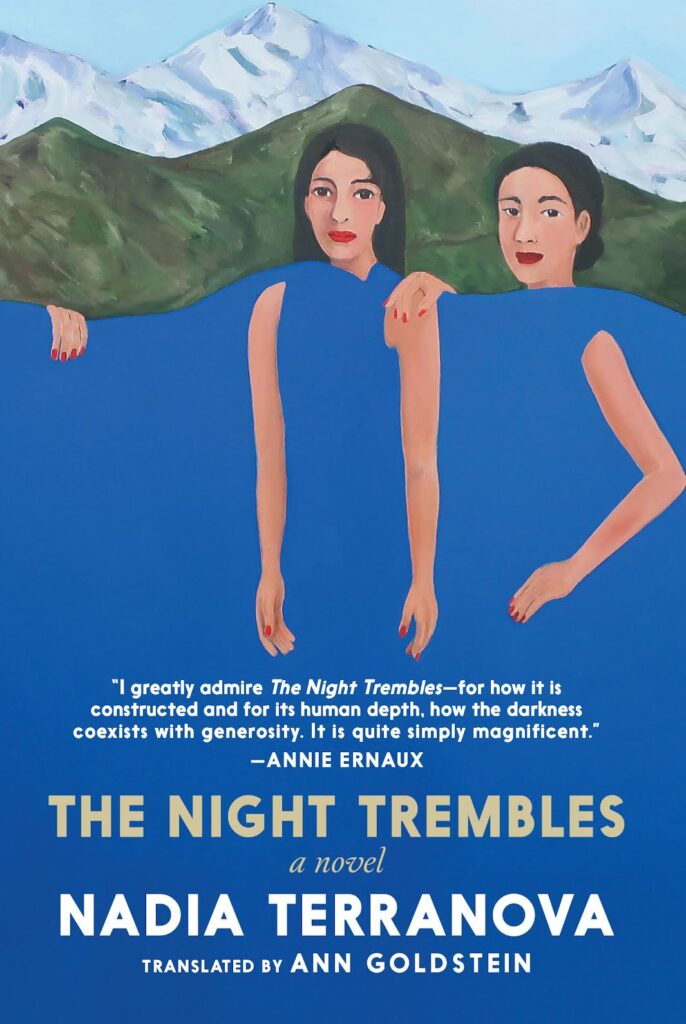

Excerpted from The Night Trembles by Nadia Terranova, translated by Ann Goldstein (Seven Stories Press).