Dad and I figured the dead cat had spent a full season wedged between tree branch and trunk. We didn’t notice until the leaves turned. Most likely, the cat got stranded further up the tree, died, and fell. Or maybe it sat in the crook until its legs went out. Either way it was unusual, the way the front feet were hanging forward and the back feet hanging backward, with its tummy pinched as if the poplar had leapt up into the air and bit the cat around the middle, like a shark. In nature documentaries, Great Whites come straight out of the water to bite around a seal, which looks as dumb-eyed as the shark itself. Even though one is being eaten and the other is eating, you can’t tell the animals apart, at least not by the look in their eye. Everything about the hunting and eating is mechanical, which is why it doesn’t disturb me. Although my mom said that’s exactly why it should.

“Cats are critters of instinct,” my dad said from all the way up the ladder, gloves on, plastic bag ready. “They don’t suffer the way we do.” But he made a horrible face all the same as he reached for the corpse.

“Fucker,” Dad said, quiet. His fist came away with a big chunk of cat, but even more stayed behind in the tree.

“Woah,” I said. “Damn.”

“Do not start, Dezi.”

“Shit, did it fall in half?” I could hardly see around his big, blue-jeaned rear, his rolling shoulders.

He looked down at me. “Why don’t you head inside and get bread going for grilled cheese? I’ll take care of this little pal.”

He trailed something leggy and wilted into the bag. There was a scattering sound, like small objects pelting dry leaves.

“Bread with the mayonnaise?” I asked, and sidestepped to see what he was doing.

The other half of the cat was still hanging up there, but Dad had frozen. He had the back of his forearm against his nose and his eyes shut. I looked at the soft weight in the grocery bag. I pulled the toe of my Velcro sandal through the dirt and made a furrow. I looked at our house, small under the high desert sun.

Eventually I said, “There’s more still hanging up there, Dad.”

“I know.” He opened his eyes. “Bread with the mayonnaise sounds delicious, babe.”

◆

A living cat showed up a few weeks later in the same tree. I was practicing faints into the garden piles Dad had raked. Hand to the forehead, swoon. I was going to take drama when seventh grade started. The trick was getting your knees to fold in a way that looked natural, meaning your hips have to drop like you aren’t afraid of the ground. I collapsed into the brown and yellow rustle, leaves and the torn-up long-stemmed bunchgrass that we couldn’t keep out of the flowerbeds. It was my best swoon yet. I fell and stayed, stretched out on the ground, looking at the late summer sky and its sad, long blueness.

A skritching sound came from the tree overhead. There was a live thing rattling through the limbs near the top.

“Dad!” I stayed on my back to yell as loud as I could. I put a little bit of panic into my voice. Swoon!

“Dezi?” I heard his work boots crunch out of the garage—today he had a Saab with a wheel bearing issue—and cross the gravel driveway. “You all right? Did you fall?”

His clunky face appeared over mine, concerned.

“I’m fine.” I smiled bigly to demonstrate, then raised my hand and pointed. “There’s a cat in that same tree again.”

“That’s what you’re screeching about?” He grabbed a handful of the grass and tossed it at my chest. “Little demon drama queen. You’re no better than your mother.”

I looked at him to see how he meant this comparison, but he was smiling. I threw the grass clump directly in his face and felt better.

He brushed himself and said, “Let’s see what it’s up to.”

The cat was a lively brown thing shifting around in the sparse middle branches. She meowed and looked down at us. Meowed.

“It’s not the Barkers’,” I said. Our closest neighbors were the only ones I knew of with a cat, but theirs was a tiny, vicious tortie rumored to have once fought off a coyote.

“I remember one of the Barkers wanting a new kitten,” Dad said. “I’ll call anyways. Call the Burrs, too.”

“Then the fire department?”

Dad gave a short laugh. “That’s only in movies. Your mom and I called about a cat in the old neighborhood, when you were very little. The chief sounded like he’d got the question plenty before. I guess they have better things to do.”

He put his hand on the back of my head. “Good thought, though. We’ll get him down.”

Neither of us said anything about how we got the other cat down, but I was thinking about the cat pieces when the gate down at the end of our long driveway squealed. The big pickup truck was coming through. Its phlegmy diesel idle carried across the front yard.

Dad said, “Holy Hell.” His hand dropped off the back of my head. “Of course she shows up now. Brace yourself, Dez.”

He turned and stalked, crackling like a fuse, toward the house. Mentioning the old days had called her down upon us: we hadn’t seen Mom for two months at least. Last time was just after I graduated sixth grade. She showed up at home unexpected, unannounced, and took me to Southside Drive-In to celebrate, dropped me back an hour later feeling sick. I had to lie on my bed afterward and try not to think about what two corn dogs, curly fries with special sauce, and Southside’s Famous Ice Cream Potato looked like mixed together wetly in my stomach. I thought about dry things, sand storms and lava rock, until I could roll onto my side without wanting to puke. Mom had told me not to order corn dogs. She finds them gross. Not that she said so directly, but she asked three times what I’d like to order, as if she kept forgetting.

Her arrival wasn’t a surprise, and it wasn’t not a surprise; every few months she’d come by and stay for a day, two at most. I could never tell if she was checking in on us or we were supposed to be checking on her. She moves houses a lot, but she stays around the Valley. She’s never far, geographically. In this part of the state, you can’t go far before running into plain, empty desert. She’ll never leave us for good.

I heard the front storm door slam as Dad went inside. I didn’t want to watch Mom drive up, so I looked at the treed cat. It was dark and delicate. The other one, the dead one, had been a big orange longhair, with brittle-looking lemony fluff. The sun could’ve bleached its hair, or the bad weather battered it around and made it fade. It didn’t make sense that such a horrible thing might happen twice in the same tree, an ugly tree, too: a whippy poplar on the northern edge of our parking lot, casting shadows across dented car hoods.

Mom pulled in. I recognized the knit of her small shoulders, the height of her head over her neck above the steering wheel. She killed the engine. With her short legs and her heels slipping on the metal running board, it was hard for her to climb down from the cab. She straightened her top and opened her arms to me like an ocean had separated us, lifted her wide smile like a chop of fresh wood.

“Dezi, come say hi,” she said. “You gorgeous girl.”

I gave the cat a last look. I wanted my mom to know that her ocean bit wasn’t selling. The earthy-colored ball flicked an ear, twisted its head. I couldn’t stand to look at Mom. She shouldn’t get to show up and make me happy. I wanted to be unhappy to see her, I wanted to be indignant, or angry, or anything besides the giddiness I felt. I wanted something else to happen, so that it wasn’t like this, exactly like this, every single time.

“Gorgeous girl,” she said again, and wiggled her fingers. She was Mom but different, a little sharper in the way she spoke, hair now a reddish apricot. Seeing her felt like looking through a window, her image limited, cut into sections of time, some of which I recognized and some I didn’t. She left when I was ten.

I went toward her. Some apparatus in me saw the distance, calculated that it would take four steps. Four steps of this size at this speed and here she was again. She had been countless steps away at her farthest. She smelled like a department store under hot lights, but beneath that, smelled like her. Cardamom is the word I always thought of, and I thought it then.

I felt her looking over my shoulder at our square little house. I could picture her expression, because Dad got the same one when she came around: eager for every bad opinion about each other to be proven right. A habit learned from each other.

“Dad went inside,” I said.

She pulled back and looked at me. I watched her pupils move across both of my cheekbones, down the flat bridge of my nose.

“You know how much I missed you?” she said.

Rehearsed, I thought. Total B.S. If she missed me she’d visit. “We missed you, too.”

I saw her note my deflection, that impersonal “we,” and hoped it hurt.

“We’re pretty lonely here,” I added, to make amends, but as I said it I knew it was the one fact I shouldn’t have given her.

“Lonely, huh?” She looked at the house again. “I doubt that very much.”

She didn’t doubt it, I could tell. I could tell she had a thick-skinned bubble of righteousness rising in her. The dynamic was always, Dad should be sorrier.

She told me she was there to catch up with Dad, check in, “But it’s good to see you, and remember what you look like.”

She tugged at the ends of my hair, held my shoulders, and put together a big, uncomfortable smile. I knew she practiced her smiles. I’d seen her do it in the mirror. This was an out-of-control smile that I knew she’d be unhappy to see reflected back at her.

“Let’s talk soon, babe,” she said.

“We could telegram. Send me a telegram.”

Her uncomfortable smile grew even less comfortable.

“Or send me a pigeon.”

She said slowly, “I don’t think that stuff happens anymore.”

“No shit, Mom.”

Her hands moved off my shoulders. “You are becoming very odd.”

“Ditto.”

“Dezi.” She hated me.

She gave my hair a last tug and turned toward the house. She followed Dad’s same line, a diagonal across the parking lot. I watched her knock just once before stepping inside. In a second she ghosted across the picture window on her way to the living room, where Dad was sure to be in his chair with the television up loud, waiting to scold her on my behalf for being so unreliable—he would use the word “flighty”—until she convinced him that this time was different. This time she’d found a person, place, or thing that she was truly invested in, and she has a right to her own life now anyway, doesn’t she? She always said that last bit like code and it quieted Dad right down.

I watched the space where her shape had crossed the window. I watched for a few minutes before I followed. There was another window on the backside of the house, and beneath it a spot in the ferns where I could sit in the shade and the cool dirt. I rolled on the balls of my feet as I walked, outer edge to inner edge, a way to be silent.

Once I was close enough to hear, I could tell from the tone of Dad’s voice that they were ready to be angry. Someone just had to say something dumb first. I crouched in the ferns and heard Dad say how he didn’t mind helping Mom through the rough patches, he owed her that at least, but the unexpected visits were disruptive.

Mom wanted to know what, exactly, she was disrupting.

Then Dad said my name. “Dezi shuts down as soon as you drive up. It’s hard for her. That’s what you’re disrupting: our daughter.”

“Oh please, don’t blame her behavior on me.”

“What do you mean, ‘behavior?’ What are you accusing me of?”

“You know what I mean,” Mom said.

There was a heavy pause.

“I don’t,” Dad said.

I spread my hands wide in the dirt and sifted it back and forth between my fingers.

Mom’s voice. “I love that she’s unique, but to be blunt, middle school is hell and she’s going to be eaten alive. Be real. She says weird things to people. She has to learn how to act normal.”

“And that’s my fault? I don’t see you acting very normal.”

“Unless there’s someone else here raising her besides you. Giving her your triple XL baseball t-shirts to wear as dresses. She’s going to be thirteen, Daniel.”

I glanced down at Dad’s shirt, which I’d pulled over my bent knees. Back in elementary we used to play a game called Gnomes. In Gnomes, we’d all crouch in the soccer field and pull our shirts over our knees, tucking ourselves into a ball. Then we’d roll around on the ground and bump into each other. That was the whole game. I saw now how it might be dumb.

My dad’s voice dropped the way it did when he was angriest. “If you want to fuck someone up, you’re doing a good enough job with me. Leave Dezi out of it.”

There was a loud wooden thunk and the sound of cans and glasses rattling together. Something tin pinging onto the floor. Dad must’ve kicked the coffee table.

“Dezi is going to be fine,” he said. The words were nice but he said them like he was scolding someone. “She’s smart and creative. You’d like her, if you spent more time with her. And she has school clothes.”

“I love her.”

“You have to know someone to like them. And you don’t know her.”

Mom’s voice climbed up a register, into pitiful. “I love her. I know you’re not getting as much help from me as you want. I know, and I’m sorry. I just need to get back on my feet. The thing with Marc isn’t going well.”

“That’s because Marc is a piece of shit.”

She started to angry cry.

“Ah I’m sorry, June,” Dad said.

“You and that Barker girl ruined all of our lives, so don’t say a goddamned word.”

Barker girl? Lauren Barker? I didn’t see how she factored in. She hadn’t been around since graduating college a few years ago, and before that just for summers. She had a low voice and very tangled hair.

“I’ve apologized for that already.” My dad’s voice was stern, but the earlier hardness had broken.

There was quiet sniffling.

“Come here,” Dad said.

“I can’t.”

“Just sit down.”

A shuffling noise as they settled on the couch. Still wrapped in my t-shirt, I tipped sideways onto the fern and didn’t even care when I felt the stems snap under my back. I kicked my feet and let gravity pull me over once or twice more.

◆

I stood under the cat tree so my parents would think I’d been waiting there the entire time. Mom came out the front door looking mushy, like she’d cried but was happy about it. She joined me under the tree, putting her hands on her hips like I was doing and following my gaze. It might have made a meaningful photo from the house, from the back, mother and daughter, me a smaller her. Dad would probably like to have that photo, I thought, although he would hate it at the same time. I know I would hate it.

You have to know someone to like them. You don’t know her.

The cat was crouched on a high limb, haunches sticking up, hips like flags, shoulders twisted at an awkward angle. It looked very small, but then again it was a ways up. I could just make out the side-to-side wobble of its gold eyes, which were turned down on us, watching in the thoughtless way that animals sometimes do.

It must’ve been great for the cat at first. She chose the poplar like any other tree, no reason to expect this one was different. The tense and release of claws would have pulled her up it. I curved my fingers and imagined a sensation like stretching but better, tighter. Maybe the cat smelled cleaner air, less exhaust, higher up. The tree trunk pointed a path into the middle of clear sky. Birds skimmed just beyond the branch tips. It would have been easy to keep going, claws into the bark. When you’re a cat, thinking like a cat, acting like a cat, what possible reason would you have to stop?

My mom looked from me to the cat. It was trying to stretch one of its back legs, but the branches were too close.

“Is the kitty yours?” she asked.

She never liked silences. She would prod me when I was with friends, during field trips or when people were over for dinner, even if I thought we were talking fine. More than once, she took me aside afterward and said people couldn’t read my mind, and it was hard to follow what I said. I had to be clearer about what I meant. Especially if I was planning to keep that unfriendly look on my face. To which I would reply that I couldn’t change something that wasn’t a choice to begin with. To which she’d say I was acting like a snit. A raunchy little snit—whatever that meant—and maybe I should keep quiet after all.

“Yeah it’s my cat,” I said. “Dad got it for me.”

That made her look at it more carefully. “Very nice. Does it have a name?”

“Snit.”

She sliced a look at me. “What’d you say?”

“It’s named Snit.”

“Really.”

See, two can play that game, is what I thought. A popular phrase with me and Dad, especially when I was moping after school, clattering things around, throwing my backpack, kicking my shoes. Dad would say, “Two can play that game,” and he’d tear the cushions off the couch, fling them onto the carpet, stomp around and fake-rage until I laughed. I wasn’t faking with Mom, though. We were both liars. I was waiting for her to bluff about the next time we’d see each other, what we’d do, how we’d hike out to the Birds of Prey refuge, take the river canyon boat tour. She’d buy me a pair of lace-front boots at the mall. I was waiting for her to promise details that I’d later forget and, later still, re-remember. I wanted her to leave already, or stop leaving.

She turned me with one hand and looked at my face. “You should start putting those freckles to work for you, lady.”

She raked her fingers through the long part of my hair like she did. It snarled like always. I sensed that she was keeping down a heavy sigh. She raked again and I shrieked, a frightening, senseless shriek that embarrassed her. If she wanted, she could take it as her final excuse to go and stay away. Our goodbye went like that.

◆

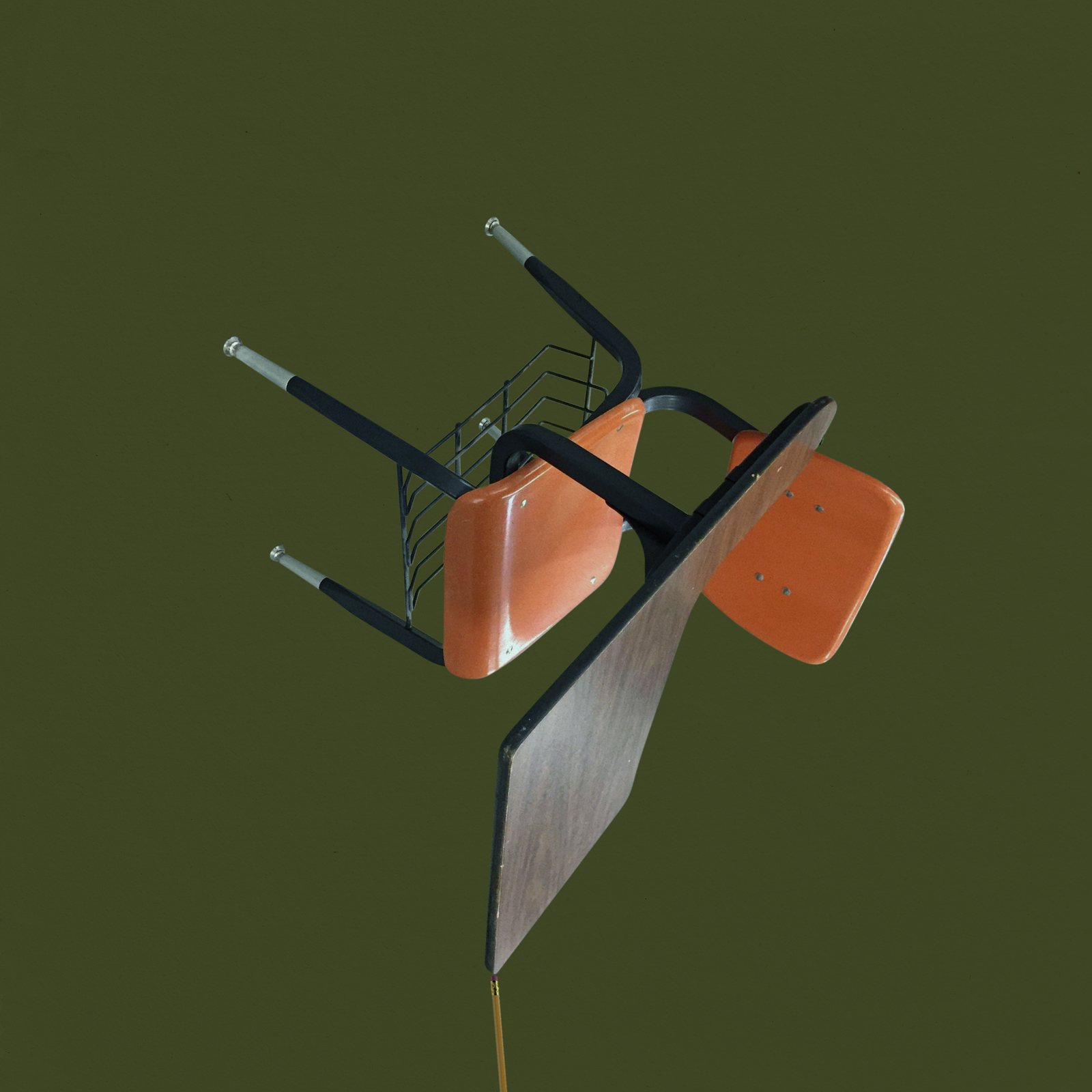

Dad usually gets one of two ways after mom leaves: he goes dark, or he gets bright and energetic, starts doing chores like replacing lightbulbs that have been out for weeks. That evening, he was the second. Energized. He wanted to go after the cat. He was optimistic at first, but the ladder didn’t quite reach. Given the thinness of the tree, it slid sideways a few times and ultimately Dad couldn’t justify the risk. He said he didn’t want to be the guy who died getting a cat out of a tree.

“And it’s not even our cat,” I said, hands gripped around the ladder as he descended. He laughed at that more than at anything I’d said in a while.

Plan B was easier. We walked to the Barkers’. Dad and Mr. Barker joked and laughed. Lauren Barker was mentioned only when Mr. Barker said Lauren had taken the new kitten away to where she lived now, so our tree cat wasn’t Lauren’s cat. Dad maybe held stiller than usual for a half-second when her name came up, but that was it. Whatever supposedly bad thing Mom accused Dad of, Mr. Barker didn’t seem to care.

We came home with a sealed baggie of dry cat food. Dad dumped all of it in a small mound at the base of the tree, took a photo of the mound and then of the cat, and posted both online asking for help. The only response he got recommended a BB gun and trash barrel.

At dinner, I edged my spoon around a bowl of hot dog chili mac to get at the hardening cheese sauce and said, “Part of the problem, Dad, is that it’s a boring cat.”

My elbow bumped his. Our kitchen table was in the style of a corner booth, ideal for no more than two, which was fine because we never had more than two.

“It’s one of those cats that looks like every other cat,” I said.

“That shouldn’t matter. They’re all the same.” Then he stopped to consider it, maybe remembering the dead cat clumps. He wagged his head like a horse. “Little future skeletons running around.”

“I just mean it’s a brown-striped-looking boring cat,” I said. “The orange cat from last year would have got more attention. Or not’ve gotten lost in the first place,” I said.

“Orange cats gets more attention?”

“They’re exotic. Because of scarcity.”

His phony deep-thinking face.

“I learned about it last year in Life Science.”

“Sure,” he said. “Sure, sure.” Then he smiled. “Scarce like your mom and her orange hair. She’s scarce.”

“You might say that.” I didn’t like his smile. “That color is fake, though. Her hair’s probably gray, under.”

He looked off at the opposite corner of the kitchen, closed his fist around his fork. His smile was strange, his teeth looked small and loose.

“She’s definitely going to marry that Marc guy she’s living with now,” I said. I don’t know why. “The decorations are all gonna be made out of cork.”

That did it: no more smile.

“Cork,” he said. He shifted around. “I’ll believe it when I see it.”

◆

Mom was back the very next day, again in the early afternoon. As her truck came in, I was in the orchard working on a project. I wanted to make a basket or platform of some kind that I could put food on and hoist into the cat tree. A food lift. I’d stripped leaves from the poplars, layered them between firm braids of cheatgrass. I had a mud mixture that I thought might hold. I needed a pulley. If I got it right, the cat would be sitting there, unsuspecting, napping maybe, and when she opened her eyes, she’d see a mound of dry food rising like a miracle from nowhere. She would tuck into the little brown crispies until her belly bulged. I could send food up twice, three times a day if I needed to. Water too. The cat would start to cry when she saw me coming across the driveway.

Mom wasn’t interested in my pulley hoist. She hollered hello across the property at me and turned to the garage. She flitted around in a floaty dress and interrupted Dad’s work on the Saab, even though the Saab guy seemed like a jerk and would definitely let him have it later. If I knew it, Dad must’ve known it, too, but he let Mom stay all afternoon, the whole length of my food lift construction process, including my search for a pulley rope (I settled on a black extension cord). They didn’t come out of the house, and I didn’t feel the need to go inside. I had nothing to say to her or Dad. I avoided the open window because I wasn’t in the mood to hear them getting along.

My attempt to hoist the lift failed on the first try. The basket handle I’d made out of braided grass was too weak. It tore off and I couldn’t get it back on. Never mind that it took three tries to toss the extension cord high enough, and while doing so, I accidentally bopped the cat on its butt and made it crawl higher in the tree. The food lift was a start-to-finish failure, although I imagined I could make a better apparatus if I spent more time on it. Maybe got some art supplies from school next week.

It was a long afternoon, and hot. I gave up on the lift and decided to float the broken basket in the irrigation pond instead. I loaded it with stones and it got a good three or four feet out to sea before buckling and going under, invisible all at once in the seedy cow-crap water. The sun got lower. I heard Mom come out and start up her engine. By the pond, I flipped a rock in my hand and thought how good it would sound hitting the side of the truck, but it wasn’t worth the way she’d come after me, the things she would say to Dad later about me and my snitty-ness. I tossed the stone into water instead, told myself I enjoyed that sound more, the splashy clonk.

◆

My dad’s new cure for the cat issue that night was to put out an open can of wet food. Mom had brought a bunch over, apparently. It was her idea.

I said, “Why is she buying stuff like that when she doesn’t have any money? She’s trying to get on your good side.”

“Nobody said she doesn’t have money.” His tone got a little quick. His mood wasn’t as light as yesterday. “You shouldn’t go around assuming things about people. Not everybody’s got a secret motive.”

“Mom does.”

We were standing in the kitchen, all the lights dim for the evening, showing us ourselves in the window. We looked unlively. Dad peeled back the tab on the cat food can and held it out to me, avoiding eye contact. He was barely in control.

“Please stick this under the tree,” he said.

The cat took up yowling that same night. I stayed awake listening and imagining its teeth shining against the garage floodlight, which it was probably sick of; I learned that bobcats prefer to hunt in the dark. By stealth, it’s called.

Maybe the cat had been hunting. She saw the flip of small wings and decided that upward was the way to go. After climbing for a time, there must’ve come a point when she slowed. The birds were gone. Maybe she relaxed, shoulders unstringing, crouching, feeling comfortable and less alert; she could’ve dozed or followed the leaves that spun in the wind.

I got out of bed. The cat had food, I figured, so maybe she was thirsty. I filled a bowl, one of the bright plastic bowls from the grocery store picnic aisle, and slipped into Dad’s oversized work boots. As I approached the tree, the cat stopped yowling. Not quite a cry of joy, but better than nothing.

I left the bowl of water next to the food and looked up. The cat was watching me. We stared at each other, or at least I stared at her bright circles until the cold, the fresh cold of fall, sent me inside. On my way back, I flipped off the floodlight on the garage. I left Dad’s boots by the door and got into bed. The yowling started again.

◆

In the morning, the cat food was still there, untouched. Dad didn’t notice until after the Saab guy came and yelled at him for being late, being a shadetree ripoff scam artist. Dad followed the guy to his car, Dad’s huge arms opening and closing, out and in, “It’s only a couple more hours!” But he drove away angry. It wasn’t until Saab guy was past the gate that Dad noticed the bowl of water and the can of food by the tree.

“The hell,” he said, and kicked the food bowl hard. It skittered and rolled sideways past the trees, under the fence and onto the Barkers’ property, where it came to rest face down at the foot of the first row of corn. Something in me went with it. He might as well’ve kicked the cat.

I ducked under the fence after the rolling can. I expected the food to have come out, but when I picked it up, everything was stuck tight in there and had a surface texture like glue, which gave me the idea of roughing it up a little. I scraped furrows into the greasy brown surface with my nail, surprised at how soft it was, like a meaty pudding. The scraped-off cat food wedged a satisfying dark crescent under my pointer finger, which I raised to my face. It smelled salty and rich.

“Dez.” My dad was watching from his side of the fence.

I explained to him about the smell, how the cat might be able to smell the food better if it was roughed up a little, like into furrows that released the scent.

“It’s not a problem with the smell,” my dad said. He was still worked up, mad but not at me. “It’s a problem with the cat’s brain. The cat brain is pure stupid, no reason. It can smell fine. Just doesn’t know what to do from there. Doesn’t understand the simple physics of up and down.”

I considered. “Can cat brain be fixed?”

“Unlikely.” Dad shook his head like he was certain.

I furrowed the rest of the food and positioned the can farther from the base of the tree, out into the driveway, upwind of the cat, thinking that way it might be easier for her to notice.

Of course Mom showed up twenty minutes later and ran it over. Her wheels went straight over the can, even though I was right there, waving at her not to. I think the truck was so big she couldn’t see me, or she thought I was saying hello, because she waved as the metal crunched. I began explaining about roughing up the canned food for the smell before she was even out of the truck. Everything got messed up around her. It annoyed me.

She was annoyed back. “That kitty can smell the food just fine without your, uh,” she said, pushing the truck door closed.

“Furrows.”

“Well he can smell it, trust me. I can practically smell it from here.” She put one hand on the fender and leaned to look under the front of the truck. I noticed then that she’d lost a lot of weight. Her hips looked flat from behind, like someone had smacked her hard with a board.

“It started yowling at night,” I said. “We have to figure out how to get her down.”

She stood up. “You’re probably just tormenting the poor thing with the smell.”

I wondered how many more times she was going to appear at our house. “At least I’m trying to help, not just creeping around while it dies.”

“Creeping around?” She crossed her arms.

We were about the same height now, I noticed. I said nothing.

“Are you through being unpleasant?”

I stared at the cat. For a second, I wanted the animal to die up there.

“Because I am happy to help if you would ask nicely.”

I felt my brain where it touched the back of my eyeballs.

In a nicer voice, one that made me feel worse, as if she had forgiven me for something I never did in the first place, Mom said, “Maybe it just wants a different kind of food, babe.”

The cat’s eyes were half-closed and the small pink tip of its nose was bumped against the wood of the branch. It held very still. You have to imagine that a long time passed up there before the cat’s nervous system registered any important change. The need for water would have gotten more urgent until the cat felt a ferocious thirst, but when it looked, there was no clear way down. The path it came up by, all the clever footholds, seemed to have disappeared. The cat maybe then climbed higher, scouting for an escape that wasn’t there. When it gave up the search, it was farther off the ground than before. She knew that jumping now would mean death, whereas going without water for a while longer meant life. As far as the cat could tell, anyway. So it waited until all it could do, all it had the energy to do, was keep waiting.

I felt sick about the moment when I wanted her to die.

“We can try other kinds of food,” I said. “Except we don’t have any. We have this wet and the dry that the Barkers gave us.”

“The Barkers,” Mom said. She looped a piece of my hair around her pointer finger. I waited for her to say something else but she looked far away.

“Yeah, Dad and I went over there. They might have more. We could ask?”

“Nah, I’ll take care of it,” Mom said way too lightly. “We can manage.” It was obvious she wasn’t thinking about it, not really. Not seriously, like I did.

◆

We spent the afternoon getting supplies. It was embarrassing to go through the checkout with twelve different kinds of exotic cat food when we didn’t have a cat, and when Mom insisted on the lane where the familiar checkout boy, Shane, the boy with the nice face, knew we don’t have a cat. Worse when his nice face changed as the beeps added up.

“All this stuff is wild.” Shane said. “Like a cat buffet. You get some new pets?”

And Mom looked at me instead of answering him. The silence and the look meant she was handing this one off: Here’s your chance, Dezi, is what she wanted to say. Prove me wrong about you.

I thought of my mom’s voice saying, she says weird things to people.

“‘All this’ in reference to what?” I asked.

Shane smiled. “In reference to the cat food.”

From his smile I got the sense that Shane might be a good audience. He might be a person I could tell about the cat and its lonely instincts hammering inward, going nowhere.

I swelled my voice and explained to him, “It’s because of the cat me and Dad are trying to get out of the tree. We don’t want it to die up there and rot and fall in half.”

My mom didn’t blink, but that’s what gave her away. She was furious. I didn’t want to prove her wrong. I didn’t want to learn how to act normal. I wanted to act like I acted.

I told Shane that we had tried a number of tactics—calling the cat, whistling at it, singing at it, laddering up to grab it, dry food, wet food, water, lassoing the cat, a food lift, a pulley system, and a roughing-up-the-surface method that still might work.

“The cat seems to be getting very tired,” I said. “It’s getting very small, like things do right before they die. So we need to try everything.” I looked at him closely. I could feel my mom staring. It felt good to dig in. “Like, everything.”

Shane nodded and his nice little smile wasn’t rehearsed, I could tell. He didn’t interrupt me as he piled our cat food cans and baggies and pouches into double-bags and held them out to us with a very strong-looking arm.

“The concern is that we had one die up there earlier,” I said. “The same exact tree.”

“That is not true,” my mom said.

“That’s crazy,” Shane said. “It’s gotta mean something, right?”

“You know the craziest part?” I spoke with enough gravity to make my mom look at me, I saw her freezer-burn eyes on the side of my face, watching my mouth as I said, “It’s not even our cat. It probably belongs to some heartless stranger who abandoned it. Left it to die.”

“Shut your mouth, Dezi.” Mom was so angry she looked frightened.

“Probably wanted it to die,” I said.

Shane’s little smile became a big smile. He grinned.

“Get the bags,” my mom said. It turned out to be our last visit to the store together. Our last visit anywhere, period. She would leave that afternoon and not come back the next day, or the following. We haven’t seen her for a few months now. If I know anything, though, it’s that guessing is pointless. And I also know that Shane’s face, right before he started laughing at my joke, looked better than ever.

◆

It’s a survival instinct, I get it. Mom wants people to like her. She wants people to like me. She saw the way I talked to Shane and how he talked back to me. My hypothesis is that it spooked her: Shane liked me, people like me. No doubt it was hard for her to stand there and listen, realizing how wrong she’s been her whole life. How she has no purpose anymore but to hand over money for cat food that she must’ve known from the beginning wouldn’t work.

Before she took off that afternoon, she lifted the bags onto the kitchen counter, looking like she had when I was little and she was worn out already from being my mom. Her elbow was crooked-up; she lifted heavy things in a way that made them harder to lift. The usual pang arrived, the apology I always seemed to have ready for her, but this time it arrived with a shadow. I wanted her gone. I wanted to be the one to snap and peel back the lid on Favorite Feline Friends “Harvest Love,” dolphin-safe wild-caught tuna and pumpkin, and I wanted to do it without her.

She wanted the same thing, so the solution was obvious to us both. She softened her shoulders and tidied her expression for goodbye.

“You behave, Dezi.” She reached for me and instead of in my hair, she put her hand on my upper arm. Her grip was limp and awkward, but I appreciated the gesture. I appreciated that she told me to behave without expecting, this time, that I’d listen.

◆

“Harvest Heart” didn’t bring the cat down. I tried grain- and gluten-free salmon. I tried six-fish “Open Ocean.” LUVABLES brand savory chicken breast and liver blend, “Poultry Paradise.” A different one every day. “Duckalicious Delicacy” was the last, somewhere around day six. Dad stopped me.

On the first day of school, I came back and the cat was gone. I didn’t ask and Dad didn’t bring it up, but I thought of the possibilities and I’m thinking of them still. It could have climbed down. It could have fallen, swooned into the leaves; it could have dragged itself off into the cool dirt under the shrubs. It might have gotten fried by lightning, shot full of BBs, or swooped by an eagle. Probably we’ll find her later on, but I guess there’s no telling for sure.