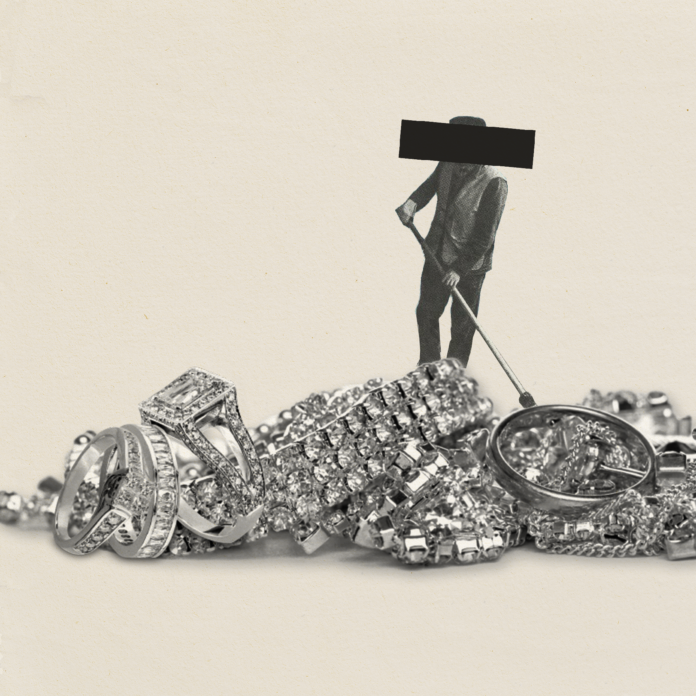

“I see your daughter around glittering things.”

That prediction, suggestive of prizes and the trappings of the good life, was hand-written on a sheet of paper torn out of a legal pad. The words, spoken by a soothsayer and transcribed by my mother, came down decades before I started working at jewelry stores, and by age 50, I had worked at eleven different shops. You could say being around glittering things was my career after I gave up on being an artist.

Nobody needs high-end jewelry. Jewelry will not shelter the homeless, feed the hungry, or clothe a cold body. Still, a quick class in how to sell jewelry can’t hurt because you never know when you’ll need to make people think they need a glittering thing.

◆

LESSON ONE

In nearly every instance, if a couple enters a jewelry store, there’s only one thing you need do right off the bat: you need to picture them in bed.

This does not mean that the couple are having sex, will have sex, or have ever had sex, but jewelry — expensive high-carat, gemstone, and diamond jewelry — is a delegation for sex. The higher the price tag, the bigger the delegation; the deeper the apology, the greater the measure there is from one half of the couple to the other half of the couple. A galaxy of intimacy can stretch from person to person, and the only object that can brook that unfathomable chasm is, say, a necklace. Jewelry is the carnal hope for heaven, the J word that isn’t Jesus.

Let’s start.

◆

A man and a woman walk into a jewelry store. You are behind the counter, eyeing your mark. You are mindful and compassionate — you are discerning the depth of the apology, the width of the crevasse. You envision laying the necklace, like a suspension bridge across billions of stars, between this man and that woman.

Stay with me, here. The woman walks around, espying items in the vitrines, eyebrows rising and falling as she goes, and she stops at what you call the sapphire cabinet and points at a ring. You head over to that area at an unhurried pace. You reach under the counter and grab a velvet tray, place the tray atop the glass, and slowly, slowly open the cabinet and remove that ring.

You speak softly and leisurely, all the while holding the ring. Music is playing in the store, music that has been carefully curated to enhance the mood. Your voice is soft because you want the customer to move in to hear you, you and nobody else. You are sharing a secret, the secret of the suspension bridge that goes from desire to desire.

You put the ring on the velvet for a nanosecond and then pick it up and hold it under the halogen lights, high enough so that your fingers burn a little, and you say, “This is an eight-carat cushion-cut untreated Ceylon blue sapphire set in eighteen-karat white gold.” Pause. “This color is rare in a stone of this size. Notice the brilliance of the blue at the meeting of the facets. Extraordinary.”

The woman glances away from the ring and looks back at it, sidelong.

Watching her, the man smiles. “Try it on, sweetheart.”

You wait another moment. You look at her. “May I?”

She nods.

You slip the object on the right ring finger, never the left, never presuming marriage, always leaving room for whatever this relationship is or isn’t.

Now, only now, does the music become key to the strategy. A cut of “My Romance” performed by pianist Liz Storey. Very nice.

“This stone was mined ecologically. I don’t know if that’s important to you folks. Some people are concerned these days.”

“We are,” she says, taking off the ring and fiddling with the tiny white tag attached to its upper shank.

The man says, “Do you like it?” As he says this, he reaches for the ring, eyes the tag, raises his eyebrows, and slips the ring back on the woman’s finger, all in one smooth move.

“It’s… .” Her voice is barely audible.

“It’s what?” he says.

“Expensive,” she says.

This is when you exit on false pretenses.

“I need to check something,” you say. You go to the desk and leave them alone with the ring.

You tinker around with paperwork. You make a phone call. You look out the window, if there’s a window. You greet another customer.

All the while, you keep your eyes on the ring bearers, and you realize that they’re arguing. Not mean arguing, but a little contentiousness over there. You change the disc on the CD player; you put on the secret closing weapon: Andrea Bocelli singing “Time to Say Goodbye.” The song is aural nostalgia, Bocelli is spinning Eros recalled, sex without any of the Sturm und Drang. Hot monkey sex, sanitized with a Tidy Wipe.

You return to the scene.

“Hi,” you say, reaching into the vitrine to rearrange the display of several other rings.

“We would like to take the ring,” the man says.

You smile at the woman. Not a huge, Macy’s Day Parade smile, just a little knowing, entre nous smile that allows for dignity in all directions. And that’s when you see her shaking her head side to side.

“I need to think about it,” she says.

“Why do you need to think?” he says. “What’s to think? You love it. I love it.”

“Thank you, but it’s all so fast.”

“Sometimes fast is good,” he says, putting his hand on her hand.

“This is the first place we walked into,” she says. “I want to wait.”

At this point, you have all the information you need to know to close this sale.

What? you say. What is all the information?

◆

This scenario is called The Hold Out, and it’s one of the most repulsive exchanges you’ll see on the floor. She wants to wait.

What is the woman waiting for? The guy wants to buy her a huge sapphire ring. Like that. Spontaneously. For no reason. Or, rather, for no reason he’s going to tell you. And she’s putting up a wall, not letting him part with his money. So, what gives? What’s going on with The Hold Out, and how do you, the seller, address the problem?

“I understand how she feels,” you say to the man. “This whole town is filled with unusual jewelry stores, and the two of you just happened to walk in here, first off, and see this ring, and there might be other things that catch her eye elsewhere, other things she likes more.”

The woman is silent. The ring is now off her finger, sitting on the black velvet like a sparrow, lonely on a housetop. The part of the story that remains unarticulated is that the woman has a nasty plan. She suspects that if the man is willing to buy her this ring, there’s no telling what else he might be willing to buy her if she just stands back and waits for something else, something better, which is why she’s not saying one more word.

“I understand,” you say to the woman. You’re laughing, a friendly, sweet laugh. “But, you know,” you say, your soft voice kicking up a notch, “If you keep turning him down, he might stop offering!” Ha ha ha ha.

“No, it’s not that,” she says, her cheeks reddening. Ha ha ha.

Ha ha ha.

Ha.

They leave, they come back the next day and buy the ring; they leave, they don’t come back. At this point, you don’t care and you’re onto the next expo because you’ve had the thrill of seeing how ugly it gets, and even the twelve percent commission (that did or didn’t make it into your pocket) is chump change by contrast to the priceless treasure of having seen how inert metal and stone can make a mess of flesh and blood.

◆

LESSON TWO

Now, let’s look at a different problem, something called The Lucky Guy.

The couple are in their seventies, eighties maybe. They’ve been together a long time, or maybe only twenty-five years, but there’s not another twenty-five-year anniversary ahead of them. Every day is a celebration.

The front door is open. It’s a beautiful summer day and the couple strolls in. He’s a glad-hander, throws himself around the room with a big voice, they’re from Okie Dokie, he’s Dell, a happy guy, wants to know your name — first and last — wants you to know his wife’s name, Carol Jean. So, there you have it. Dell and Carol Jean, and they’re in town for a week staying at a vacation rental, and it’s clear from the get-go that there’s a lot of disposable income and it’s just a matter of who’s going get that windfall, what with so many shops in this town, and you’re not going to have any push or pull with that, of course, because the cash will be disseminated according to Dell’s whim.

“I’d appreciate it, greatly,” Dell says, “if you see to it that my wife has everything that she needs.”

Carol Jean is at the showcase containing a hand-fabricated necklace by a jeweler from Idaho. You grab the velvet tray, remove the necklace from the vitrine, place it on the velvet, and adjust the necklace so it forms a perfect circle. It gleams under the lights.

“This is a piece by Jim Walker, who lives and works in a small town outside of Ketchum. His lapidary skills are peerless, a mosaic-maker of sorts. You have lapis lazuli — amazing gold flecks in those stones. Tomato-red Mediterranean coral that, because this deep scarlet material is increasingly rare, the artist recycles from vintage pieces. And Sugilite — an unusually vivid purple. Are you familiar with Sugilite?”

“No.”

“It’s is a mineral found in only a few mines in the entire world — on the Iwagi Islet, in Japan, where it was initially identified in 1944, and in isolated locations in Eastern Canada, South Africa, Italy, Australia, and India.”

It’s helpful to intoxicate the customers with the kinds of facts that evoke the sense of global travel.

“Oh,” Carol Jean says.

“You also have, here, natural American turquoise from the Royston mine in Nevada. The necklace is set in high-karat gold, twenty-two-karat gold.”

“Please tell me about that clasp,” she says.

“This is called an S clasp, and while it’s not what you are accustomed to seeing in traditional jewelry, such as on a piece by Van Cleef & Arpels, or Cartier, this kind of clasp is often used by artists in handmade pieces.”

Carol Jean runs her forefinger over the curves of the clasp.

“It’s easy to use,” you say.

You look up at Carol Jean. She is wearing a brightly flowered sleeveless blouse. And in that moment you see what you didn’t see when she and Dell first came in, when Dell was bursting at the seams in the middle of the store.

Carol Jean has one arm.

◆

You say, “May I help you try it on?”

“Dell?” She’s not looking at you. Her voice, so low, so quiet, sounds smothered.

Dell is standing in front of a small antique Russian icon on the wall about thirty feet away, but he responds to Carol Jean’s call as though it is the third alarm for a three-alarm fire.

Now, as you might have already figured out, you will spend the next ten or fifteen minutes repeating the exact words you have said to Carol Jean to Carol Jean’s husband before you have been vetted sufficiently to assist him in helping her try on the necklace. He lifts the price tag before he finishes his task and, nothing: poker face.

And it’s on. You walk over to a full-length mirror and beckon the couple to join you. Again, you guide them through the various stones, the fabrication process, the biography of the artist, and, if relevant, the names of collectors who have acquired the artist’s work.

“We don’t care about any Tom, Dick or Harry who owns that necklace,” Dell says. “We make up our own minds.”

“Of course,” you say. “But, the fact is, Dell, you and I both know that not every Tom, Dick or Harry can own that necklace because when you buy that Jim Walker necklace for Carol Jean, you’ll be buying something unique. No two of this artist’s works are alike. Each is one-of-a-kind.”

That’s in case Dell has an expansive definition of unique.

By the way, this is called the closing stretch. Carol Jean and Dell are by themselves now. You’ve left them alone, and you are pretending to be busy at the front desk. After a brief interval, Dell approaches you.

“Okay, Ms. Zimmer. Do I get the rabbi’s discount?”

“Ah. A fair question, Dell.” You are not smiling. “Are you a rabbi, Dell?” Do not smile.

“Do I get a discount, Lina?” Nervous lick. Ha ha ha.

“The name is Linka.”

“Linka.”

“Thank you. Well, since you asked, Dell — not everyone asks — but since you asked, I’ll see what I can do.”

You have a margin on all the pieces in the store. In the case of the hand-fabricated works, the artists set those margins. With the necklace chosen by Dell and Carol Jean, you have fifteen percent leeway.

“I can do it for twelve percent.”

“We’ll think about it,” says Dell.

Carol Jean is silent. Carol Jean has been through this routine again and again, on every birthday, every anniversary, every Valentine’s Day, every year on the date of the amputation. Every time, she has to go through this thing with Dell.

As they cross the threshold, a turn of events that increases the likelihood of their buying something elsewhere, you will worry, you will feel like a failure, you will juggle regrets.

Your mandate now is to master the most important technique in selling jewelry, in selling anything — even an idea: you must be willing to hear “No” before you will ever hear “Yes.” Before the husband calls the store later and makes a fuss, attempting to pull a fast one, trying to get the merch for half off, you must be willing to walk away.

◆

Dell calls the next day. In this case, it’s a major production. You end up going to the vacation rental, with the necklace, going through the try-on business all over again, discussing the price, and arriving at the terms you want, which makes nobody happy. Well, nobody but you. Fifteen percent. That’s it.

How?

This is how.

You’ve got the necklace on Carol Jean all over again and she’s in front of the mirror in somebody else’s house, a stranger’s house, a vacation house.

“It’s a lovely piece,” you say to Carol Jean. “Suits you.”

“You don’t need to sell it to us,” says Dell. “We decide all by ourselves. I don’t think we like the price you gave us.”

“I would like to give you a better price, Dell. I really would, but I would be devaluing the artist’s work, and, in turn, your investment. The artist has allowed us only so much room to move on this piece. I’ve given you the best break possible.”

“I doubt that Ms. Zimmer. I doubt that very much.”

Okay. You’ve got to just let that go. Just. Let. It. Go. And keep talking. And you talk like this:

“I’m starting to wonder whether you realize how lucky you are, Dell. Whether you realize how lucky you are to have someone to buy something for.”

Carol Jean isn’t the weeping type. She’s all cried out.

You leave the room.

Dell follows you out and tells you they’ll drop by later with the credit card.

◆

You backtrack into the room with Carol Jean, undo the S clasp behind her neck and slip the necklace off — noting her shoulder, the smooth plane of skin-wrapped bone like a sudden cliff, a rock face like Half Dome. You place the necklace carefully in the box, quietly leave the premises, and drive back to the store.

◆

“Why do you still have the necklace,” your boss says. “Why didn’t you close the effing sale?”

You’re thinking, how do you expect me to close the sale without Bocelli singing “Time to Say Goodbye?” What am I supposed to do, carry around a portable CD player with little speakers? How would that look? How subtle is that?

You don’t say that stuff. You just think it.

You tell your boss that you’re holding the necklace just for today. Your boss is indignant and wants you to put the necklace back in the case, back on the floor, but you defend the sale, you say that you have a good feeling about it.

In fact, you’ve got no feeling about this because you’re still thinking about Carol Jean’s boney cliff, but as you start to lock the door for the night, Dell shows up on the other side of the glass door with his Gold card and his big gut and his glad hands.

◆

LESSON THREE

The sale of jewelry is almost always about sex, which means that sometimes it’s not about sex, it’s about something else, and whatever else it might be about is usually loss. The loss situation is most often found when you see a woman alone crossing the threshold. Even a man crossing the threshold alone could be coming in to buy a gift: an engagement ring, something of that nature. Don’t count him out as a sex tale in the making.

◆

Loss: that’s an animal all its own. I’ll tell you a personal story.

This guy comes into the store. Corduroy jacket with the pile worn down, mustache like tumbleweed trapped on barbed wire. This person has been unloved — unloved with violence.

“How are you doing, today?”

“Okay, I guess,” he says.

In silhouette against the bright windows, he moves as if carrying a mountain on his back.

I unlock a case and arrange the men’s bracelets.

“I’m just looking,” he says. “Just poking around.” He ambles toward the case where I am, and I pull out a bracelet, withdraw a polishing cloth from my pocket, and start rubbing the silver.

“Do you live here?” I don’t look at him as I polish away for a while, and then I lift my head for a second to make eye contact.

“No, no. I don’t live here. I’m, I’m here on vacation,” he says. “Sort of vacation. Kind of a rest, I guess. I just had surgery, back east. Just taking a little time off. A retreat. A rest.”

“Good idea,” I say. “This town is a great place for a rest, unless you’re working!” Ho ho.

Ho. I blink at his left hand. No ring. He catches me.

“And my wife and I got divorced last year, so.”

“Sorry,” I say. I place the bracelet back in the case.

He peers through the glass. “No, no need to say sorry. It’s fine. That bracelet, the one you …”

“This?”

“To the right of it.”

I grab a velvet tray and place it on the counter, bracelet on top.

“It’s twenty-two karat gold, handmade by a local jeweler using an ancient Etruscan technique of braiding and granulation. The decorative pattern near the clasp is created first by making the tiny gold beads and then fusing them to the surface of the bracelet. The trick is that the temperature cannot be so high that the beads melt. It’s a difficult process to master. My name is Linka. What’s yours?”

“Jeff.”

“Hi, Jeff.”

“Hi.”

“What do you like about the bracelet?”

“I don’t know. It’s unusual. I’ve never seen anything like that.”

“The artist shows his work in select galleries throughout the world, but we’re lucky to have the first pick of everything he makes. Would you like to try it on?”

“What the heck.”

I lift the bracelet and hold it in both hands, like it is the first boy-child of a couple that have had four miscarriages. I wrap it around Jeff’s wrist, trying not to touch his skin but not deliberately avoiding his skin. Once I link the clasp, I touch the back of his hand and let my fingers linger a second before I stand back.

“Suits you,” I say.

“Bet you say that to all the customers.”

“Actually, no. Sometimes. Or I try to steer them to something else if I think what they’ve chosen doesn’t work for them.”

Jeff touches the part of his hand that I touched.

“Walk over to the full-length mirror and take a look.”

Jeff does as he’s told.

“I think it’s a masculine piece, if that’s important.”

“It’s not. I don’t really care about that,” says Jeff.

It seems to me that Bocelli might not be the way to go with this guy. I am unsure which way to go at all, what to do with a divorced guy who’s just had surgery, probably serious surgery.

I walk over and stand beside Jeff at the mirror: I, in my work clothes, all black. I note a sharp pain migrating from the back of my skull, searing across my scalp into my left eyeball, threatening to blossom into full migraine.

“Where are you from, Jeff?”

“A smallish suburb back East. You wouldn’t know it probably. Larchmont.”

“You’re kidding. I’m from Montoac!” I say, a little too loud.

“Cool! I grew up in Montoac!” he says.

“No way,” I say. He pronounced it correctly.

At this point we’re both shouting, “Wow! Montoac! Nobody’s ever even heard of Montoac! Nobody can even pronounce it!”

“Where did you live in Montoac?” I say.

“Pemican Road.”

And I’m thinking, weird. “What number Pemican Road?”

“215 Pemican Road?” he says.

“I lived at 215 Pemican Road,” I say.

We look at each other in the mirror and then turn, face to face.

I feel woozy, out of the world.

“So. You are Jeff Filler,” I say.

He nods.

“Your mother was in our house,” I say, knowing full well how strange that sounds. “Your house. The house.”

“In the house,” he says. No interrogatory tilt. Not even a real surprise in the voice.

I tell him about the things that used to fall off the shelves, the arcs they would have had to make in order to land in the places they did, in the center of the den.

“Which room was that?” he says.

I explain the layout, moving my hands in the air to show where the front door was, where the bedrooms were, where the den was — which is when he stops me cold.

“That was Mom’s room,” he says. “That’s where she was when she fell asleep with a cigarette. That’s the room she died in, in the fire.”

◆

There’s a couch in the corner of the store that’s reserved for closing special sales, a place where the customer and the salesperson can talk and have some private time, wrangle over the price point.

“Why don’t we go collect ourselves?” I say, as if the act of collecting — or the acknowledgment of anything as unmoored as ourselves — could dispel the eldritch atmosphere of the moment. Jeff nods.

The sofa is upholstered in brown Dupioni silk. I sink into the mud-colored down cushions and feel Jeff, like a seesaw, sink down beside me. He is seizing his share of the luxury, and there we are, feeling all this opportunity and clarity. We don’t look at each other.

The CD player runs out of discs. I am the only salesperson in the store at the moment, and I know I am supposed to keep the music going, keep it on all the time, but I don’t get up. The room feels hot enough to melt my face.

“Is it hot in here?”

I am sure I can taste the gold warming against Jeff’s wrist.

A breeze sweeps through the front door.

◆