The nodes would always adhere to the circuit. Every day at four in the afternoon, with six hours of studio time down and two to go, Thora’s back and neck would ache, the walls of the cavern behind her eyes would ache, pins and needles would dance inside the calluses on the tips of her fingers—not the pads, but the crowns, the rounded part closer to the nail—from handling the little black boxes at the end of the thin red wires, but at least the nodes could always be counted on to adhere to the circuit.

The intricacies of the work were new to her, but Roman was right: the systems Bruno had them building were so straightforward that a fifth grader with a solid attention span and slightly above-average recall could have done it. This was something Bruno stated openly in artist talks, but with his serious, raked face and resonant voice it sounded modest and intelligent, grounded in well-established theoretical concepts. “It’s really very basic stuff,” he liked to say, “basic building blocks, zeros and ones.”

For reasons Thora assumed were various, Bruno’s self-deprecating candor about his process did not include his studio assistants. Or at least it didn’t seem to. She never heard him refer to their work directly, not even when prospective clients and industry people came to visit his Brooklyn studio. Burners, mostly; middle-aged musicians and tech CFOs who flew from Los Angeles in cowboy boots and expensive bootcut jeans. From her work bench Thora watched the artist’s hands as he spoke, silhouetted against Apastron #21 or #32 or #44, part of a longstanding series of flat, square “light sculptures” that hung on the walls like pastel paintings—the overhead lights were always turned off for these visits, the blackout shades drawn, a few almost-finished pieces illuminated and roving. His voice dissolved into the drone of the computers and the HVAC, the particles and their velocities.

The Burners liked to look over Thora and Roman’s shoulders and coo or nod or ask Bruno questions as the assistants pretended to snake wires and plug ports. Thora knew without being told that she was not to stop performing purposefulness and productivity, despite the fact that the small, buried mouths of the transistors melted, like Bruno’s voice, into the dark. Customers were not to be made to feel guilty for their presence. Guilt was bad for business.

Surely the visitors could see even less than she could. But it seemed inconceivable to these people that Thora should share the limits of their perception. Unless they didn’t see her at all? Their obliviousness seemed to say: here you are not a body, you are nobody, you are nothing. It was a relief.

◆

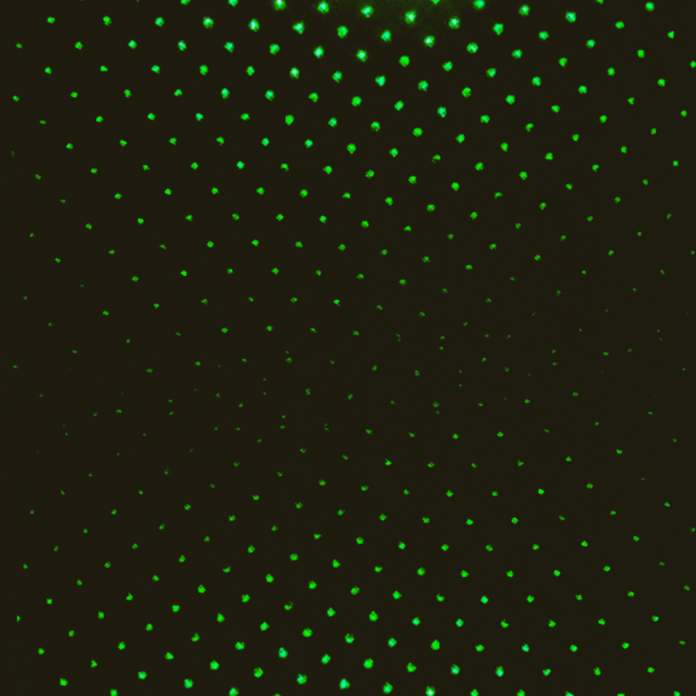

Since graduating from Yale’s conceptual art program almost a decade earlier, Bruno had amassed a considerable fortune—though without the kind of name recognition that would have impressed Roman and Thora’s friends—building his characteristic light sculptures. Or rather, instructing his studio assistants in how to build them. Thora and Roman constructed the sculptures using LED bulbs and printed circuit boards, “PCBs” for short, which hid behind sheets of steel punched with round holes of varying sizes and densities. Bruno programmed the circuit boards to feed instructions to the LED bulbs using computer code he wrote himself. Each individual bulb could be told what color to turn and when.

The code was based on a mathematical hypothesis called “The Game of Life.” The Game of Life consisted of three main components: first, a grid of pixels or small squares; second, a short list of rules that determined how a pixel—or, in this case, a bulb—would behave, and third, a set of “initial conditions”—a few pixels illuminated in a particular pattern, for instance—that the rules would act on indefinitely once you pressed start. Because both the rules and the initial conditions were set from the beginning, the state of every bulb could be predicted from the get-go. The light’s only job was to obey.

Bruno had not asked his assistants to study up on the Game of Life. He hadn’t asked them to understand anything about the concepts behind the art they were making, probably to avoid having to pay them extra for their time. But Thora did it anyway. She lost track of the hours she’d spent doing it.

The Game of Life predated computers by several decades but could now be “played” online. When Thora opened the website, she was presented with a boundless gray grid in which five yellow squares were illuminated, always in the same configuration: the shape of an ‘L’ that had fallen over on its back, plus one additional square attached at a corner to the L’s foot. The first time, Thora pressed start without altering the configuration at all. The shape began to turn and tumble diagonally down and to the right. After about fifteen tumbles, it fell off the visible section of the board entirely, and she had to go looking for it, zooming out on the mousepad with her thumb and pointer finger as if the grid were a digital map. It felt somehow invigorating, Thora thought, like following someone you loved through a crowd.

She counted the number of revolutions until the yellow ‘L’ was restored: two. That plus the continuous downward motion made it a “spaceship,” as opposed to an “oscillator” or a “still life.” It looked like a pixelated body falling in slow motion down a flight of stairs, forever.

The hardware Bruno outsourced to Thora and Roman. What they built could not be seen with the naked eye—once completed, the PCBs and Swiss-cheesed sheets of steel were covered in thin lids of white acrylic, which diffused the light from the bulbs into blurry, galactic shapes. Some of the shapes rippled or shifted awkwardly like audience members; some danced or thrashed under their white sheets. Apastron #44 wavered with concentric rings of orange and fuchsia. It reminded Thora of an eye staring into a fire, or perhaps an exploding planet; around the edges of the panel, behind the rings of orange and fuchsia, lay a charred realm of black.

During client visits, while the lights were off, Thora let her eyes slide out of focus until the cityscape of circuits and wires doubled before her. The thin red wires were roads, the thicker black wires were highways, and they met and diverged, dipped underground into small holes in the steel backing and resurfaced inches away before rounding the corner of a black or gray power distribution unit and docking at a port in its side. Each unit reminded her of the actual port of Oakland back in California, and in particular of the barges you could see from the BART train just before you got sucked into the tunnel under the Bay. A barge scaled down to the width of a business card, with diodes and capacitors arranged just-so on top like shipping containers. The PCB components were the size of Legos. Some green, some yellow, some black with little blue lids.

She felt no nostalgia for these superimposed images from her childhood. Maybe there had been an ache in the beginning, but now they were just facts, visuals that produced other visuals in arbitrary, if unfortunate, patterns.

◆

“Did you know the word ‘gimmick’ is an anagram?” Thora asked Roman one morning early on in their tenure at Bruno’s. “Gimmick” was Roman’s favorite way to describe the product of their day job. He said it with a growl at the back of his throat and a murderous set of the brows, though the eyes beneath them were curiously void. But he looked that way most of the time: as though, overcome with feeling, he’d removed himself from the room.

Thora sat at the kitchen counter in their apartment, drinking coffee while he made a fried egg. Every item in the kitchen predated Thora except a few replacement plates and the green spatula in his hand, which they’d bought together at The Big Reuse shortly after Roman took her in, dusty but new, with the barcode sticker from TJ Maxx bonded to the handle. The egg slopped into the pan from the shell silently, without a sputter from the oil. He was impatient, Thora thought, that was his problem, and his impatience had made him bitter, as if the fevered, accelerating stage of his life were already over.

“What,” Roman said.

“Of the word ‘magic.’ Or no, it sounds like an anagram of the word magic. Magicians used to use it as shorthand. For a type of trick.” She’d heard it on a podcast the day before. They both spent most of the day listening, separately, to one type of audio material or another. Thora’s hearing had been quickly fine-tuned so that now she could operate on three planes at once: (1) the world being fed into her ears through short-wavelength ultra-high-frequency radio waves, (2) the real world, with its collage of bioacoustic and electric noise, and (3) the world inside her head, where she chopped up the signals from the first two and braided them with her instincts and judgments and questions, her heartbeat.

“Huh.” Roman’s back was turned.

She summarized the critic’s analysis as best she could, which was not very well—as badly as Thora wanted to be what she considered a principled person, she struggled to organize arguments about the ideas that shimmered for her, judging their worth only by an urge to sit up straighter, to blink often. The crux of the episode was that gimmicks were “tacky magic,” but magic nonetheless. Their meaning just seemed phony because their form was so…visible, so easy to replicate. People want magic to wear its runes under its sleeves. She remembered that line.

The egg began to sizzle and pop. Roman turned to face her and leaned against the counter, his sweatshirt hood up. “Don’t tell me you’re joining the cult of Bruno.”

She exaggerated the roll of her eyes for his benefit. When they went out with friends, Thora laughed along at his hyperbolic descriptions of Bruno’s patrons—the media theory professor with the self-help bestseller; the sallow models who were only there because they couldn’t get their hands on a James Turrell; the Argentine transportation magnate who knew Bruno’s parents, and who spoke to him in a particular Spanish that changed the tectonics of his face, lending it a happier cartography. (Thora alone had noticed the last part, and she wasn’t talking.) The many faces of Bruno—she imagined superimposing every mental snapshot she’d collected of the artist in a big stack of transparencies, a Cubist photocollage. Bruno would put his name on it, but they would both know the truth. They would share the secret of her necessity. It was a truer self-portrait, anyway, made by someone else.

“I’m not saying I like his work,” she said. “Necessarily.”

They argued. Roman’s words were fierce, but his tone was even, almost bored. Thora’s was lively, teasing, but on the chess board in her head the pawns were on the offense, creating a buffer of space where she could think.

Roman’s antipathy for the lightboxes seemed to her the cynicism of expertise, a result of knowing too much. When Bruno showed in galleries, the text on the walls just revealed the usual: title, year, dimensions, things like that. Materials were listed like a vague family recipe: acrylic, powder-coated steel, electrical hardware, custom software. The code was the only ingredient in the recipe that Thora and Roman did not know intimately.

He stared at her. “So you’re saying it would be good art if we knew less about it?”

“No, I just—”

“The dude is just on some recycled Warhol Factory bullshit.” Roman turned his back again and nudged the egg’s stuck edge from the pan with a fingertip. “But worse. It’s all digital.”

Thora’s eyes lit upon a small object on the windowsill: a geodesic dome carved from scrap wood, a rigid mesh shell of contiguous triangles. Roman had whittled it last year. At a tangential point on the dome, the shell dipped inward as if it had been depressed by a fingertip. It was really an amazing little thing. What if, for the next five, ten years, all Roman produced were crumpled geodesic domes, tessellations of a tessellation? Would he heap the same scorn on himself? Everything she wanted to say shimmered in her peripherals, blurry and indecipherable, arguments about the nature of agency and of creativity, of the questions worth asking and the materials that could articulate them. A philosophy effervesced there, out of reach.

◆

Every evening, Thora and Roman stood up and gathered their things at six on the dot. They waved a curt goodbye to Patti, Bruno’s assistant-assistant; the artist himself left hours earlier. Roman’s thing was, if you were going to have a job-job, you better take advantage of not being taken advantage of. They would be efficient and reliable for eight hours a day. Then they would shut off like machines.

They parted ways in front of the Lowe’s. Roman went off on his usual errands or odd jobs; he always seemed to have friends who needed help carrying furniture up four flights of stairs or installing their new show in a gallery in the Meatpacking District, and he often secured contracting gigs for extra cash. Thora cut across the parking lot toward the pedestrian walkway across the canal. The warehouses she passed were unlabeled, occupied by companies and suppliers for other companies that made things using quantities of materials she could only comprehend in the abstract. As May elapsed, then June, the evening light retained the optimistic blue of afternoon, and she savored it, stopping to close her eyes in the parking lot before the overpass eclipsed the sun.

She liked the hum in the air in this part of Brooklyn. The polyphony of breath from the cars on the interstate and the vibrations from the 495,900 kilowatts of power coursing through the 2,500 miles of cable that powered the subway system. Bruno was always talking about making sound without sound; the movement of light in his pieces was often interpreted as a visual representation of acoustic waves, and people liked to ask in Q&As and interviews if he ever set his pattern sequencing to music. A deeply stupid idea. Thora could feel his disdain through the computer screen. He handled the stupidity with his usual monotone solemnity, which came across as grace, though his reply always boiled down to “absolutely not.” It tripped Thora out to think about how right he was, how sound would have sent his work into the realm of trite Disney bullshit, a fireworks display on a wall. Katy Perry in the background. Okay, more like Sigur Rós, but still. The line between art and gimmick—cheeseball lava lamp commercialism, airport water feature cliché, spectacle—was as thin as a melody. It was like in horror movies, or films about war and genocide: there was a reason why certain scenes were the most arresting, the ones where a village gets firebombed in total silence, or automatic gunfire tap-dances across a black screen. Horror could be made more horrifying by divorcing the senses, by isolating them from one another, and maybe it was the same for beauty, too. Not that beauty was the point. Awe, maybe, which was like beauty multiplied by horror; it took everything you’d ever seen and hollowed it out.

Tunnels of thought like this one excited Thora. It was like exercise, mental constitutionals. She could feel the metabolic pathways opening and closing, laboring to expel the detritus accumulated during the workday.

Watching Bruno’s interviews was like hearing a pop singer live for the first time and discovering that there was a reason they were famous and you were not. When she brought it up to Roman, the contempt in his face confirmed she would never be able to convince him that Bruno might be a talented person, or an intellectual person, or better yet, a principled person. You couldn’t talk someone into awe. And least of all someone like Roman, who trusted his own instincts automatically and stubbornly. The men were too similar, Thora decided; in art and in life, they made rules and set conditions.

After arriving home, Thora managed to temporarily resist the call of her laptop by running five miles through the cemetery. She took note of the baubled white perennials, the hexagonal stones tiling the path toward the mausoleums, moss efflorescing in the grout; she took note of the Civil War veterans’ headstones strung in punctilious rows along the hillside, ivory and rounded at the tips like teeth. Since starting at Bruno’s, she saw LED bulbs everywhere, everywhere tessellations of shape and light.

◆

Patti, Bruno’s assistant-assistant, was a gaunt, thin-lipped woman who was either forty or twenty-four, and who didn’t look like she would be organized on account of her short black bangs but was. On the days when Bruno didn’t show up to the studio, which had become more frequent, Patti arrived in the mornings to remove the padlock on the door and “get them set up,” though their stations were always exactly as they’d left them the day before.

Patti sat at her own table with a laptop for a few hours before leaving to dart around the city like a blackbird, returning in the evening to lock up. Once or twice each morning, between rapid-fire grant applications and emails to wealthy people or their proxies, she released balloons of B-rated celebrity gossip into the air in a small, frail voice, which amused Thora and drove Roman crazy. Patti hadn’t looked like the type of person who would be interested in B-rated celebrity gossip, also on account of her bangs. But Thora was learning you could never predict whose lives had touched whose. The algorithm worked in mysterious ways.

At the beginning of August, when Thora and Roman had been working for Bruno for several months, Patti greeted them at the door with news. Bruno had secured a contract for a large-scale permanent installation in Berlin. The client, a museum, was relocating to an old colonnaded stone building in which unspeakable horrors had been choreographed, if not committed during the second world war. While the wings were under construction, a one-of-a-kind panorama of an ancient Greek city occupied the welcome hall. Bruno’s installation would effervesce on the ceiling, a new cosmos.

“We’re all very excited about the opportunity,” Patti said. She looked at them with expectation in her forehead.

Roman glanced at Thora, eyebrows raised; they realized simultaneously that the announcement was also an invitation.

Neither of them was offended at the implication that they could just pick up and begin a new temporary life somewhere else. “Ask me again in a month,” Roman said to Thora later that night. There would be other jobs; Roman was the rare New York native, knew everyone and could make anything out of metal or wood or latex, and as a result they were never out of work for long.

The month elapsed, and within the week Roman had contracted carpal tunnel. His right wrist radiated heat; he said it felt like someone had twanged the tendons like a banjo. Thora listened and asked interested questions, but his complaints had started to make her vision go cloudy, her hearing far away. Their inconvenient bodies. At work, she focused on attaching red wires to their green ports. When the light box was done, Bruno’s custom software could ask the LED bulbs to turn sixteen million colors, sixteen million permutations of red, green, and blue.

Thora sometimes wondered if Roman was right, if Bruno would continue churning out light sculptures as long as he lived, or as long as he could sell them. That was the greatest trick of all, Thora thought. Given the same constraints, every iteration would arrive eventually, and maybe it was the case that the magic of art, or the magic in the gimmick, was that you would certainly die before that happened.

◆

Roman’s wrist did not improve. Or rather, it improved only when he was not at work attaching nodes to circuits, which he could only afford not to do for two days out of the week. Soon it went without saying that he and Thora would be staying in New York. Their friends had seemed sorry for them at first, but Roman’s indifference, which verged on disgust, slicked whatever surface their pity tried to cling to. A finish line was good, they decided. It’s not like Bruno would struggle to find replacements.

Meanwhile, Thora began to devote her remaining time alone after her evening run to what she called, to herself only, her “research.” Her hair still damp from the shower, she would pop the tab on a can of diet soda, open her laptop, and click into The Game of Life.

The game was meditative, like chess, but with just one ‘move’: the first. She set the initial conditions, clicking certain squares from off to on, dead to alive, and pressed start. After that, every move, every turn, was carried out by the computer to its logical conclusion.

The game’s parameters were inspired by that of physical liquids: each square cell behaved in accordance with the way the cells next to it behaved. Thora liked that. An organic substance broken into geometric shapes, distilled down to its most basic building blocks, as Bruno would say. And this liquid behavior was, as the game suggested, an apt metaphor for the behavior of human beings: if a cell had two live neighbors, it survived, unchanged. More than two, it died by overpopulation. Less than two, it died by underpopulation. A dead cell could be revived, ignited yellow, by three or more live neighbors, which of course impacted its neighbors, sometimes killing them by overpopulation or reviving others, and so on. The game had no written goal, no expressed way to win, but this was Life: Thora felt an innate urge to keep at least a little light alive, to keep it moving.

When Roman asked her what she’d done that evening, she cited calls with friends she hadn’t spoken to in months. Without the film to prove it, she couldn’t use photo shoots as an excuse, so she settled with disappointing him, leaving seemingly empty the time and space she had asked for when she’d moved into his cramped studio apartment. It had been her only condition.

She didn’t have to speak to him—to tether her incoherent, unprincipled curiosity to the trellis of language—to know that she wouldn’t be understood. The conversation was like the images in her head, the photographs she had stopped taking; she could envision the placement of every object in the tableau, could anticipate precisely how the camera would interpret depth and shape and spit out a feral topography of line and shadow. That was the problem. If the concept already existed—and not just the concept, but its form—what was the point of making it real? Just for it to be seen by someone else? No. She was in a new phase in her practice, she thought with a self-respecting dose of irony, a sort of post-practice, which was also post-language. It was exciting.

At night, Roman slid inside her in the stale moonlight that reflected off the brick building catty-corner to their own. Bruno appeared in her mind’s eye towards the end. She traced the grooves around his mouth, which invoked authority and experience, the fossilized evidence of some vanquished suffering, and he looked back with a warped square of blue light in each eye—even in her fantasies, she knew he was looking not at her but at his monitor with its strings of nouns and symbols, pressing start on chains of cause and effect that none of them fully understood.

◆

As the Berlin project approached, Bruno’s presence in the studio waned to a sliver, and Roman brooded at work more openly. “Where’s the boss?” he asked Patti without looking at her, and she responded with the distracted diffidence of someone who knows she’s the butt of an inside joke. Behind Patti’s back, when Thora caught his eye, he counted down their remaining weeks at the studio by holding up a number on his fingers, tugging the sleeve of his black hoodie over the heel of his good hand with his remaining fingertips, a quirk that made him look like a little boy inside his thirty-two years.

On the first Wednesday in October, Roman, Thora and Patti received a new shipment of fuses and power supplies from Meant Well and spent the morning unboxing them. (Thora smirked each time her gaze passed over the brand logo; how immediately unconvincing it was to come right out and say so, that the brand’s brand—meaning essence, or the distillation and performance of that essence—was their professed innocence and good intentions.) The boxes advertised “extremely low” no-load power consumption, which meant they consumed minimal resources when plugged in but not turned on. True no-load energy does nothing of use, Wikipedia said.

“Did you know Ava Max shares a stylist with Bjork,” Patti whispered.

“No,” Thora said. “I didn’t.”

Later that evening, while Roman was helping an artist friend install a show uptown, Thora opened the Game of Life in a new tab and regarded the grid with its yellow ‘L.’ She added one yellow square to the shape and began clicking additional cells in the grid at random; a polygonal cluster in the top left corner, a few angular shapes dotted here and there among the gray like yellow seagulls. Then she pressed start. The altered yellow ‘L’ became a pinwheel, then a gaping oval, like a mouth, where it stuck. She sat up a little straighter in her chair. Her first still life! Her heart skipped, and she chuckled inwardly at herself.

The parameters of the code dictated that a state of stasis had been reached: each illuminated cell would continue to survive as the game’s “turns” ticked by, but without igniting any additional cells, without producing anything new. The turns accumulated on what looked like a digital clock at the screen’s bottom right corner.

She pressed stop, rewound the play, and watched it back. If the death of every yellow cell felt like losing, a still life felt like a draw.

In the chess games she’d played with her grandfather as a girl, during the long, dark stretches when she lived with her mother’s parents in their big house in Marin, she never understood why you’d declare a game a draw, or when. How many turns before you knew nothing could surprise you, no mistakes would be made? You had to have complete trust in the competency of your opponent, and that was ridiculous, that her quiet, strange grandfather should trust her not to do something stupid, especially when she got tired. Now, in her research, she was learning that human error wasn’t the only factor; she was always coming across mathematical hypotheses that had been proven, problems solved, simply by testing enough permutations of variables. So-and-so found that such-and-such shape would perform in a new way after one thousand one hundred and three “generations,” et cetera. And weren’t quantum particles always spontaneously changing course? On the screen, she watched the “clock” and felt a pregnant sense of potential. If she let the game run for another hour, two hours, three, what if, what then?

◆

On the second Wednesday in October, when Thora and Roman returned from lunch, the lights in the studio were off and the blackout curtains lowered. Whomever Bruno had been touring through the studio was already gone, along with Bruno himself, or else they hadn’t yet arrived. Patti was seated at her usual table, typing.

“Are we good, or…?” Roman asked.

“Let’s give them a few,” Patti said softly. “In case.” Roman caught Thora’s gaze and raised his eyebrows; paid minutes of forced inactivity made him disproportionately mischievous and triumphant.

They sat beside each other, close enough to hear the other speak in subdued tones over the white noise. Roman scrolled on his phone while Thora stared absently into the room. The Apastra murmured silently on the walls. The movement of light was subtle but constant. And that was when the question struck her: how could the movement be constant? How did Bruno’s code avoid a still life? She almost laughed in surprise. Or—and this really felt like something—could a still life be avoided? With enough time, sufficient zeros and ones, even years down the line, would the light snag on an outcropping and stop?

She imagined the clients with the cowboy boots and expensive denim descending their clean, broad staircase back in Los Angeles—pale adobe, it would be, no rug—and finding their light portal frozen on the wall like an overloaded browser. They would grip each other’s hands in dismay, the way parents did in Spielberg movies: what did it mean? Was it a sign?

“Maybe he’s never coming back,” Roman said. He had hitched one foot onto the workbench and was leaning an elbow on his vaulted knee, picking a hangnail.

She laughed automatically. “Yeah, maybe.”

“Maybe he’s dead.”

“Wishful thinking?” Thora hoped Patti wouldn’t hear.

Roman shrugged. “Maybe.”

She laughed again.

“Maybe I killed him.”

Roman had once been inscrutable to Thora, she remembered, and this had agreed with her; they’d found each other in their eyes only in select, unpredictable moments, seated opposite one another on the train or wordlessly agreeing on the triteness of a friend’s new tattoo. Those moments had felt fated, as if they’d bumped into each other in another country.

She held an invisible microphone toward his mouth. “Why’d you do it?”

“For the money.” He didn’t have to say duh. “It’s the perfect crime—we keep working, and no one even knows he’s gone.”

“No one?” She jerked the invisible mic in Patti’s direction.

“I have his phone. Got a text here says he’s gone on a retreat, back to the Land of Fire or wherever he’s from. Too bad about Berlin.” Roman balled his hands into fists and scrubbed at his cheeks like a mime.

“And Patti handles everything on her own?”

“She does what she’s already doing, just like she’s doing now, and so do we.”

“Diabolical.”

“Not really. Bruno loves being dead.” Roman swung his free leg like a child, satisfied.

Thora couldn’t help herself. “What about the code?”

“Getting real detailed, I see.”

“Not really.”

He looked at the ceiling and pretended to think about it, or he really was thinking about it, it made no difference. Then he looked at Thora. “You,” he said, gesturing at her with a sweatshirt paw. “You went to college for a little, you’re smart. Zeros and ones, right?”

The image of the yellow still life glowed in the upper quadrant of Thora’s right eye like a sun shadow, bright-dark.

Roman’s tone rankled her. “How, in your professional opinion, do you propose we keep the light moving?” she wanted to say but did not. Patti pressed the button. The blackout shades peeled upward, and the windows coughed light into the room.

The conversation unsettled Thora; over the next few hours, she found herself glancing often at Roman to see if he could tell. Was he avoiding her gaze or simply working? This was another facet of his principledness: things either mattered a great deal or didn’t matter at all.

You could be content as a principled person in this ecosystem of artists and studio assistants, Thora thought, only if you were comfortable with not just invisibility, but nothingness; with not mattering a great deal and thus not mattering at all.

Thora distracted herself for the remainder of the workday by listening to a podcast and daydreaming, testing her ability to travel along the third plane of her consciousness, above direct sensory input. Eventually she came upon the building in Berlin where Bruno would build his next commission. She walked up the steps and into the welcome hall. The 360-degree panorama on the walls consisted of hand-painted panels that had been digitized and projected on a continuous, curved white screen, like the walls of a bowl. She thought about Bruno’s home country across the ocean to the south, and in particular about the soldiers who had been trained by soldiers in their home country, hers and Roman’s and Patti’s, to do nightmarish things with electric torture devices in buildings just like the one in Berlin. And from this third plane, this impossible future-past, she felt Roman grow even farther away; Roman, with his belief in the ineffable soul of artistic creation, in the hand on the object that obeyed the hand.

◆

Patti was late getting back from her afternoon errands. The clock struck six, then five past, then ten, while on Bruno’s desktop computer a band of purple light wheeled in perpetuity against the black screen. Roman had another install date with his artist friend uptown, and he grew quickly irritated, cursing under his breath. When Thora had told him to just go, she would wait, he went without a fight.

She watched his black hoodie retreat down the block from one of the windows and felt hyperaware that when, every evening, Roman withdrew to one of the many locations where he helped bring art into the world, she had no idea where he actually was.

At half past six, she felt a soft pressure on her right shoulder and jumped. Patti leapt back, her face pale as always.

“Sorry,” she mouthed. Thora removed her headphones.

Patti’s hair was stringier up close. It was the first time the two of them had been alone in a room for an extended period, but Thora felt an immediate camaraderie between them, if a strained one. The strain was due in part to Thora’s uncertainty about where they fell in relation to one another in the studio hierarchy, and in part to a more translatable complexity: the currents of wariness and relief that pass between women who are used to spending most of their time with men.

Patti’s gaze fell on Thora’s headphones. “What were you listening to?” she asked. The question made her look twenty-four.

Thora described the podcast, the kind where gracious, open-minded non-experts talked to awkward, narrow-minded experts about their research. Today’s episode had been about dream faces—how psychologists found it difficult to prove whether the human brain could invent new people, or whether it simply generated composites of repurposed ingredients, noses and cheekbones and proportions you might have passed on the street but which had evaded the conscious mind.

Patti nodded. “In my dreams you’re always played by Maya Hawke,” she said. “And I’m Rooney Mara.”

Thora blinked. Who was Maya Hawke?

“But every man is Mark Ruffalo.”

Thora cackled in surprise. Did Patti dream of Roman, who resembled Mark Ruffalo as much he did a turkey sandwich? Bruno?

“Bruno too?” she asked.

“Not exclusively,” Patti said. “He sort of rotates between a few. Last night he was Gavin Rossdale.” She began to bustle around the room, flipping switches and pressing buttons, deactivating everything but the air conditioning and the no-load energy coursing through the cables. Thora waited, feeling useless. Apastron #44 hung like a dead window on the wall. She tried to imagine the topography of Bruno’s expression at that exact moment. Which face was he wearing?

The women left the building together and started across the parking lot toward the subway platform.

“So,” Patti said. “No Berlin for you two.”

It struck Thora that this was a question Patti had been waiting to ask her, and not only that—she had been waiting to ask her the question when Roman was not there. Thora shook her head.

Patti frowned. “Couldn’t find a subletter?”

Thora considered her options and decided on a euphemistic strain of truth. “Roman’s sort of ready to move on.”

She said nothing of his carpal tunnel. Roman was a fiercely private person, and besides, Thora had forgotten it—that is, until a few minutes after Patti posed the question, when it no longer made sense to bring up.

Patti was quiet for a moment. A car honked on the interstate; above their heads, the elevated rail’s steel skeleton gurgled under the weight of the train. There was no true silence, Thora thought to herself, just the decision not to disturb what could pass for it.

“It’s a wonderful opportunity,” Patti said. “To travel. I think you’re making a mistake choosing not to.” Her youth disappeared abruptly into the thin line her mouth drew in her face.

Was that what she was doing? Thora wondered. Choosing?

As they walked under the overpass, they passed a scrapyard to Thora’s left beyond a chain link fence. It held only disembodied windows, their frames stacked upright like books.

How could she explain to Patti that this specific choice would signify other choices to the person whose name her interlocutor had studiously avoided, new allegiances? Or at least new lines of inquiry, which themselves signified new allegiances?

Behind the fence, a man got out of a pickup truck and entered the scrapyard. He strolled the rows with purpose, flipping through a stack of windows as if they were posters or records in their sleeves. Patti was speaking quietly but insistently about Berlin, about the island of museums that had once been the center of the old city and about the upcoming Biennale.

Thora’s mind wandered once more to the Game of Life. In the game, the outcome of the causal chain could be predicted by the initial conditions because the rules were known, preordained. But Bruno had never said his code was replicating the game exactly; he said his code was inspired by it. Thora had never considered before this moment that one of the rules could be that the rules were allowed to change, that new sequences of zeros and ones could latch onto the old, that the program could keep feeding on its own exhalations like the whole organic respiring world. Maybe not even the code could predict how or when the transmutations would occur. There were simply no still lifes allowed. Thora felt a vacuum of disappointment open inside her chest—that was it? But just as swiftly, the vacuum contracted again, compressed by new questions with strong hands.

“Anyway. I’m not going to tell you what to do,” Patti said in her small voice. “Don Cheadle said in an interview I heard the other day that when people tell you what you’re going to do, it tends to come true.”

Patti made Thora promise to think over what she’d said, then disappeared in a wingbeat up the stairs to the train.

◆

When Roman still had not returned to the apartment by eight, Thora grabbed her camera and a roll of expired film and went out walking. The sky was a deep but insistent blue despite the hour, as if the world had experienced a childlike burst of energy just before bed. She found herself retracing her steps, toward the elevated rail and the scrapyard of windows between the cement pylons.

Thora paused halfway at the new park overlooking the canal, which was no longer diseased, or so people said. Three teenage boys were playing by the waist-high fence. The high-rise office buildings of Downtown Brooklyn peeked out from behind a high-rise apartment building if she craned her neck. She imagined herself again inside the entrance hall of the recently converted museum in Berlin: the panoramic view of the ancient city on the walls showed various scenes of civilized life, with digitized replicas of soldiers and philosophers that swiveled back and forth in the marketplace like animatronic statues. There were goats and cows and sheep slated for slaughter on the steps of the temple, and roving clockwise over the scene were broad, soft shadows, which belonged to clouds that were implied but not represented. She saw in her mind’s eye, standing on the steps beside the goats and cows and sheep, a congregation of studio assistants, magicked back in time hundreds of years; she imagined all the people like her and Roman in all of New York City and San Francisco and Berlin—and in all the cities her life had never known and never would—converging on the museum like ants on a morsel of hot dog. Under Bruno’s cosmos of light they waited for a new assignment, for a patron to lead them away by the hand.

One boy swung a leg over the fence, then the other, holding on behind his back with both hands while his friends crowed, egging him on—to do what, exactly? He had nowhere to go but down. Thora unscrewed her lens cap.

Roman’s absence dogged her. She would walk around and let more new things happen to her, she decided; she would let her body tell her where to go until the very same body forced her to stop. She did not take the picture, but neither did she screw her lens cap back on.

At the base of a streetlamp, a galaxy of pennies lay scattered on the sidewalk. They glowed in the light like portholes, as if the glow were coming from a hidden room under her feet—especially the new ones, with their brazen copper patina. She squatted to pick one up, then several more. She shifted her weight from foot to foot, admiring how they winked and sparkled on the ground, gauging how little she had to move to rob them of their light.