“Of course the cleanest room in my parents’ house is my dead sister’s,” Henry says.

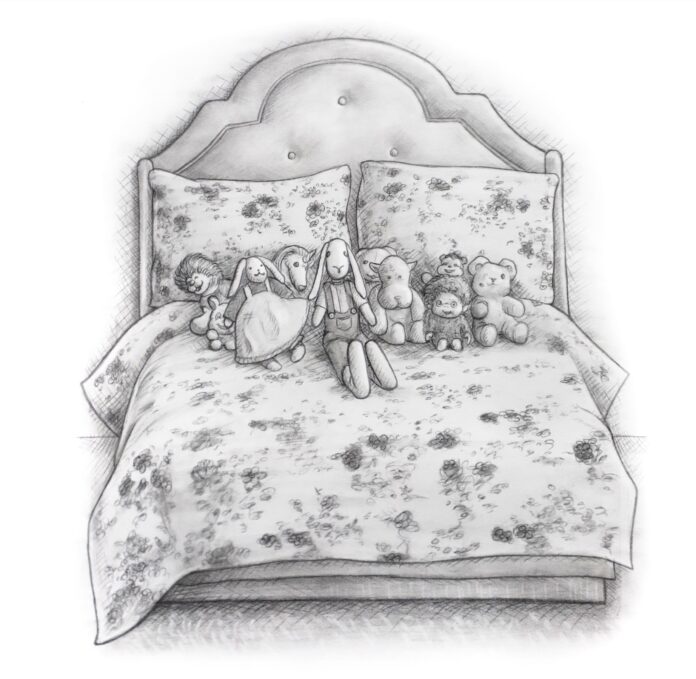

The gold metal threshold separates the hallway and her bedroom but we’ve decided not to cross it, not yet, our bare feet sticky on the hardwood floor. In my head, I count the number of years I’ve been told have passed since a body has slept in her bed. Roses the color of waterlogged blood bloom across her bedspread; they rest peacefully beneath a totem of stuffed animals. Half-formed buds poke out from between a teddy bear’s legs and yellowing rabbit dolls with body parts that look like polyester sausages. The sunlight filters in through wood-framed windows and illuminates the lemon walls. I’m unsure if the walls have yellowed by nature’s touch or by man’s. From the doorway, I see a collection of porcelain dolls in the French Curio cabinet glaring at us from behind the glass. It’s been ten years since Bridget died. I’ve only known Henry for nine.

When I told Henry that I was taking the train back to our hometown for the long holiday weekend, I didn’t anticipate his invitation. He was also planning to spend the weekend there; his parents were away and had requested he keep an eye on the house. If I wanted to come over and hang out for a bit, I was welcome to. He’d even give me a tour.

I assumed that he was going to skip this part of the tour altogether and casually refer to it as a guest room. That we would pass by without weighted thought, but Henry makes the first move into the room, and I follow. He pulls open the bottom drawer of the cherry wood dresser to show me how his mother has kept all her clothes inside, neatly folded and tucked away. He opens each one to reveal unused piles of jeans, sweatshirts, and panties. “Take whatever you want,” he says, but I don’t touch a thing.

“Good thinking. She’d lose her fucking mind if anything went missing,” he says while I’m still confused as to whether or not he’s made a cruel joke.

The scents of Downy, potpourri, and dust crowd into my nose. He tells me his mother dumps her clothes out every few months and performs a thorough cleansing.

I want to hold his hand, but he starts laughing instead. It’s true that we both possess a dark sense of humor, but I have to admit I’m not always certain of Henry’s motivations. I mirror his laughter and soon I am thinking what he must be, conjuring an image of a woman upturning the drawer’s untouched contents into a laundry basket, mixing relics with clothing of the living. As I continue laughing, my initial desire to comfort him quickly devolves into judgment of her.

You don’t realize how much you associate things with people until people aren’t here.

“It doesn’t make any fucking sense,” he says between gasps.

We aren’t dating but everyone else thinks we are. Sometimes I think we might if he were capable of it. I like to think Henry is trying to make up for whatever emotional connection he’s lacking when he invites himself over and makes dinner for me every now and then. Nothing says I love you but I’m emotionally unavailable like a bowl of spaghetti with pesto, garlic, and shaved Parmesan. Most of the time I tell myself I don’t really care that much, that some people just show affection differently than others. Last night at my place in the city, Henry prepared the food with a stoic face while I waited for the water to boil. I listened to the bubbles as they built against the quick chops of Henry’s knife, the veins in his arms rising through his skin. I hung onto the moment almost too long, the water on the brink of boiling over, before throwing the raw noodles into the pot and pushing the tops of the spaghetti down with my hand until the steam burned my palm. Henry held up a slice of Parmesan to my lips and I took it like an offering. I savored the salt on my tongue.

My laughter settles first. As Henry’s trails off, we notice how the room has been staring at us. Porcelain dolls glower with stern eyes that say more than Henry and I could say to each other. A mouthless teddy bear’s presence seems incongruous among the linen rabbits with their linked limbs and sewn-in smiles. The setting sun reveals the air to be heavy with dust. The carpet begs to burn us, the bed whispers, use me. I notice how silent Henry and I have become, how small the space is between our bodies. Henry says, “Why don’t you spend the night?”

Henry’s bedroom, despite its name, does not have a bed in it. There is only a desk, a dresser and traces of his sixteen-year-old self. His Pink Floyd poster reminds me of the time when he came back from Afghanistan and we got high and accidentally watched The Wall on repeat in my apartment. My kitchen counter was drizzled with dried chocolate crust from the Valentine’s Day gift I had been making for my boyfriend at the time, but the strawberries’ chocolate coverings were still a cold slush when I told Henry it would probably be okay if we sampled a few. I counted out five and placed them on a plate between us, our bellies pushed into the carpet and our elbows edging our faces forward towards the television. By the time my boyfriend came home from work, I had been back and forth to the kitchen three times. I held up the last one, half bitten, and asked Henry if he wanted the rest while my boyfriend locked himself in our bedroom.

“I sleep in the basement when I visit now but there’s a cot in the closet I could set up for you here,” Henry says.

“No, I want to be with you,” I say as an incredulous smile spreads across Henry’s face, “I just mean, well, it’s right over there. I’d rather not be up here, alone, next to it.” I point towards his sister’s bedroom.

There are no photos of her anywhere in the house. I can’t remember exactly what she looked like but people were always talking about how friendly she was. There was an article in the local newspaper about how she organized volunteers to mentor girls in STEM at the local community center. She was also captain of the track team and not because she was the best or the most popular but because she genuinely cared. I knew of Henry back then, but only as some intriguing, quiet mystery that sat at the back of my bus. He spoke occasionally and when he did, it was mostly to tell people that they were wrong. When Bridget died, everyone knew who Henry was. People who had rolled their eyes at him in the hallway stopped to ask if he was okay. Kind words suddenly came from people’s mouths. I hadn’t said anything to him since I’d never said anything to him prior to her death. For a while, I thought it would be too gross to use the tragedy to engage him. By the time I got the nerve, Henry had started driving himself to and from school—sometimes I’d see him walking to his car early through the window of my fifth-period class.

Henry leads me to his basement where he’s set up a mess of blankets, sheets, and pillows on the floor.

“You can sleep on the couch if you want. I still haven’t gotten used to sleeping in a bed yet.”

“What happens when you sleep in a bed?” I ask.

“I just toss and turn all night. It doesn’t feel natural to me anymore. Can’t fall asleep unless I’m on the floor with a few blankets,” he tells me.

“What if you slept in a bed with another person? Have you tried that?”

“Ha, that seems even more unnatural to me,” he says.

“If something happens, I guess it’s easier to already be on the floor. Is that what you’re thinking?”

“Probably,” he says.

“Well, if it’s any help, I think you’d be just as efficient sleeping in a bed. In fact, I think you’d be the most efficient out of everyone I know,” I say.

Henry looks like he wants to laugh but doesn’t. My instinct is to nudge him playfully and coax out his laughter but instead I diminish this emotion and move further from him. I sit on the couch and sink into the cushions.

“Is it the dreams?” I ask.

“I don’t dream,” he says.

My first year in college, a series of photos appeared in my Facebook feed of a little girl with gold-flecked eyes outlined in dark pencil. She couldn’t have been older than eight and in the first few photos she held a pomegranate out towards the camera in one hand and dragged a dusty beanie baby on a leash with the other. In the next, she carried a baby boy in her arms. There was no caption, just the name of the publisher, my high-school non-friend and brief bus fellow, Henry Lamari. I added Henry on Facebook the year he enlisted in the army and began a romance with his combat photography. I eagerly tapped through his portraits of Afghan civilians and men popping up from Army tanks like jack-in-the-boxes. They broke up my social media feed of initiations from the Divine Nine, Latino Caucus updates, and photos of my colleagues guzzling beer with bloodshot eyes, puffing on blunts.

Henry was doing something different. He was capturing a life I couldn’t see from where I was, a life that was happening at the very same time as mine. His seemed to include more risk and meaningful encounters than my standard college education and massive debt that I was slowly accumulating. There were photos of men laughing while holding large guns, farmers with stern faces posing in their fields. How easily Henry fit into the wardrobe when his friends turned the camera on him. His green eyes glistened hard, his skin tanned even deeper by the sun, black hair hidden by a pakul and a wild black beard grabbing his chin. He disappeared into the culture, a culture he never bothered to claim until the army made him. Henry would tell me that this is why he was seen as valuable to them, because his blood was mixed with both the civilians and the enemy. His mother had taught him Farsi as a child and he was one of the few that could communicate. I hit message:

Decoy paragraph to catch the illuminated initial

BETH: Hey. We went to high school together. You might not remember me.

HENRY: I remember you.

BETH: sorry, hit send too quickly. just wanted to say, I really enjoy your photography. Hope you’re doing okay over there.

HENRY: Thanks, but it probably means nothing.

BETH: What means nothing?

HENRY: My photographs.

BETH: I think there’s meaning there.

HENRY: If there is, I don’t think it’s good.

BETH: You might be right, but meaning is meaning regardless of what it means, right?

Over a year, our exchanges became more friendly.

Decoy paragraph to catch the illuminated initial

BETH: My roommate told me she was moving out today, now I have to find someone new to split this rent with. don’t need this shit right now.

HENRY: Are you asking me? because I’m kind of far…

BETH: Lol. no, smart ass. but I gotta go, talk to you later.

HENRY: Goodbye, feel better, find a roommate, kill them, inherit their life savings, and continue the process until someone potentially catches on

HENRY: then you get rid of them too

HENRY: until you’re surrounded by bones and decaying bodies

HENRY: probably didn’t need to take it there.

Henry decided not to re-enlist after his contract came to an end. By then, our conversations had found depth.

Decoy paragraph to catch the illuminated initial

HENRY: you go through so many emotional ups and downs and little conflicts in your own head.

HENRY: its fine. you are a good person. but emotionally you shift. Frequently.

HENRY: I am no better.

BETH: But how does one change that? Not saying that you should or I should…just how

HENRY: don’t know. Don’t care.

BETH: I think you feel things though

HENRY: I do. I just don’t care.

BETH: why though

HENRY: what does any of it matter?

BETH: because. if nothing matters, then why not just care?

By then both of our minds had lost most of their sugar, but we found an unspoken solace in each other’s miseries. We were good friends now.

But just friends.

The lights from a passing car reflect against the basement wall as I switch off the overhead lights and pull the beaded cord of the green glass table lamp. Henry leans over from his spot on the couch to pass me a joint. I suck hard while hanging off the armrest. As the energy from my lungs floats into my head, I let my arm fall back next to Henry’s. His shirt feels like it’s been washed a million times, the incense smoke snakes around him and mixes with the scent of the lavender oil I have started applying behind my ears. Someone once told me that body oils are a personal experience because another would have to be so close to catch the scent. I want him to inhale me, to be devoured. My shoulders sink into the quicksand of my own body. When I’m high enough, I finally turn my head to look at Henry and ask him where the scar on his nose came from. Before he can answer I am making up for lost time, grabbing his sinewy arm and outlining his tattoos with my fingers. I’m asking, “What does that mean? Where did you get this one? How’d that one feel?” He gives into my grip. He lets me pick out dirt beneath his fingernail with a toothpick I pull from between his lips. Whatever barriers there are between us are lost in a blurry fog. He tells me about the Chinese mythology that stretches over his left arm.

“It’s a representation of good and evil. Nüwa is a deity.

“Who’s this guy? He looks like he’s on her side, helping her out,” I point to another character outlined in black ink.

“That’s Fuxi, he’s another deity.”

He lifts and shows me his inner arm where an upside-down hand with an eye in its palm is inked into his skin. He lets me study it, and I trace the bumps of color that outline a letter.

“What’s the B for? Beth?” I ask while still touching Henry.

“Oh, uh no, that’s for my sister.”

“Oh, of course. I’m sorry, I was kidding.”

B is for Bridget.

I roll up my left pant leg and lay it across Henry’s lap.

“Have I shown you this before?”

“Your leg? No, but I’ve noticed that you have two.”

“This!” I point to a small tattoo of a ghost. “It’s a ghost!”

Henry looks briefly at it then turns on the television.

“I got it because it kind of represents the unknown, the things we’ll never know or at least in this physical form and how that’s okay. I accept that.”

“Ghosts aren’t real,” Henry says without looking at me.

“It’s not about whether ghosts are real or not. It’s just about the unknown, the big mystery. It’s about my interpretation of life, my choice of meaning.”

“Whatever you say,” he says and puts on Jeux d’enfants with Marion Cotillard and Guillaume Canet.

“This is my favorite movie. You know they’re together in real life?”

“I know,” he says. I am unsure to which of my comments he is replying.

Sometimes I can’t tell if Henry even likes me, as a person. I wonder if he is just keeping me around as a companion, someone to be nearby so he isn’t lonely or left alone with his thoughts. The problem with this is that I think I like him or maybe I just really like that he seems to want me around, even if I am just serving as a barrier. I think part of me appreciates the barrier, that we could never be what everyone else thinks we are. I have always been this way, preferring to harbor desire by kicking my legs off the dock but never submerging my body into its waters. I have always been curious about the things and people that both elude and encompass me. Sometimes I think that maybe I killed Henry in a past life and am somehow meant to redeem myself in this one.

I can tell Henry is only pretending to sleep so I crawl down beside him. He makes space while his stare rises to the ceiling. There’s a baseball bat leaning against the couch beside him.

“Sometimes I think I hear noises coming from there,” he says, “I know that sounds stupid, but I feel like…she’s haunting me.”

“That’s not stupid. It would freak me out, too.”

I wonder if haunting is the best word, I wonder if he means to say protecting.

“There will be footsteps in the middle of the night or the stairs creak when nobody’s home and it freaks me the fuck out.”

“Have you ever gone to check?” I ask.

“Fuck no,” he says.

When Henry has finally fallen asleep, I am woken up by the sonorous snores escaping his mouth. I drift upstairs for a glass of water and hope he’s stopped by the time I’m back. In the kitchen, I can hear the house settling. I guess which cabinet houses the drinkware and on the second try, I am successful. The clay mug I choose looks like something that belongs in the Museum of Natural History. I remember Henry’s footstep comment and my mind tricks me into thinking I hear them too. I turn the faucet on full blast but the house is still settling once my ancient mug is full so I stand there and let it overflow until I’m sure the sounds are gone. The kitchen table has a cotton tablecloth with a pattern of poppies. I place my mug in the center of one. I notice the ashtray holds the roach we smoked earlier, so I fumble in the drawers for some matches and take a drag. Instead of going back to the basement, I sit down in Henry’s parents’ living room. There are two couches that face each other. They sandwich one of those wooden tables whose belly is glass. The fireplace looks unused, but it still has its tools tucked beside it. A grandfather clock is angled against a corner, leaving a triangle shaped space behind it. The fireplace mantel displays different sized vases, carefully placed in pattern by alternating height. I sit on the couch facing away from the window, closest to the front door. I place my mug of water on the wooden octagon side table. It feels good to curl up on the couch.

It’s still dark out when I wake up but the birds are beginning to call the dawn. I wipe my drool from the flowers on the couch; use fresh spit to rinse the crusted spit from the side of my mouth. I can’t remember where the bathroom on this floor is so I climb up the stairs half asleep, grasping the handrail like it’s one of Henry’s mythological arms. Everything is Henry. I’m peeing with the door open when I realize that the door to Bridget’s room is closed across the hall. I leave the bathroom light on as I walk over to inspect.

We left it open when we went downstairs, didn’t we?

I loom in front of it. I question myself, then rush the door. My fingers look for the light switch but there is no life left in any of the bulbs. I search for solace in this empty click, trying not to panic. A rectangle of light on the bedside table flashes on. The cell phone’s light reflects on Henry’s face, asleep in bed. I exhale and enter the room. I feel my way to the window and open it; I untie the curtains and let them sway. The sun is reaching up from a corner and the night sky is entering an ombre of light. I am still high. My intoxicated mind circles the past moments of this place. Henry didn’t find Bridget until the morning; she’d been that way for hours. Been is what I think but is that the word I mean?

The sound of the bed shifting breaks my stare and I turn to see Henry turning over and back again. He is trying to avoid something or fight it, thrashing beneath the blankets. I pick up one of the stuffed animals that he’s kicked onto the floor. I squeeze its leg as I say with a stern softness,

“Hey! Henry! It’s okay! You’re safe. We’re safe. It’s okay, it’s okay!”

I approach the bed while repeating my assurance, hoping it will penetrate his subconscious somehow. Henry suddenly sits up, his eyes open and he is breathing hard and fast.

“Henry?” I say, “You were having a nightmare…”

It takes him a second to register me and where he is. I wait until the confusion leaves his face before touching him. I place my hand on his shoulder.

“Take a few slow, deep breaths. You were moving a lot so that’s why you’re out of breath.”

He pulls me beside him as we match each other’s breath. I slip my hand onto his chest and over his heart. His hand rests on mine. It feels as if this is the closest we have ever been. His chin is tucked atop our hands as he breathes and settles. When he looks back up, his lips catch mine. Our deep breaths rise and fall into each other’s mouths. Our bodies boil. His hands have moved to other places on my body. I still have one hand on his heart. This is, without a doubt, the closest we have ever been.

I am through with Henry’s pants after a few swift tugs, I claw at his neck and I bite deep marks into his shoulder that will make someone ask, where did you get those? How did it feel? He lifts me from the bed into the darkness and against something cold, my sweat marks the yellow wall. I push back against him, with him. We listen to the porcelain dolls shift melodically, resonating with our bodies. I grab the handles of the drawers as he lowers me down because I do not trust that he will not drop me. Soft fabric tumbles out after me as we fall onto the carpet and his mouth bites at my ear and my back responds with a pleasurable arch. I pull him so close that his whisper sounds like a scream when he says,

“I feel like you’re haunting me.”

What is the absence of fear in the face of danger? Love? I want to understand what it is that makes things wrong with Henry. Was his fear the opposite of love or the very hot and hidden core of it?

When Henry had told me about the people in his photographs, I could understand his resistance to everything. He said the hardest part was to be joking with someone one minute, and the next they were dead. Not only when it happened to him but also knowing that he may have caused the same pain for others. The man popping up from the army tank, a friend, had been shot in a raid. The farmer in his field became the victim in a botched mission. The little girl in the photo had taken a wrong step a few days after the photograph, she was blown apart. The only one who had survived to his knowledge was the baby brother she had cradled. But even that, he warned, he wasn’t so sure about. If he was still alive, he wasn’t sure how long he would be or what kind of life was awaiting him if he did survive. I had been too enthralled to see what his photographs really were to him—a catalogue of the lost.

Was this why there were no photos of Bridget in the house? They don’t want her to be lost. Why was he looking for her in me?

Henry tenses, noticing how my own body has frozen at his statement, reluctant to absorb it or what it means. His body follows mine. He starts to pull away slowly.

“I, I’m sorry, I don’t know why, I don’t know why…” until he’s quietly sobbing and mumbling “what a thing to say” beneath his breath.

Things can make a man; things can break a man.

I want to pull him close, to answer his questions with my body. I feel my body loosen, just a bit.

“I don’t know either,” I say and kiss him. And we fall into each other once again.

◆

A car door slams shuts. Henry registers it before I do. It happens so quickly that I don’t have time to notice how tangled together our bodies have been. My leg recoils from Henry’s hip before my eyes are even open. I’ll have no way of knowing if his arm had been resting on the curve of my waist as we fell asleep. I am desperate to know these things, these small moments of intimacy to hold onto when Henry pulls away again. I reach over to the phone and look at the time. 10:07am. He is standing by the window by the time I sit up.

“Shit,” he says while closing the window and tying the curtains back to their original position.

The front door opens and closes. I throw off the sheets and search for my pajama shorts, but all I can manage are my socks and Henry’s shirt. My frenetic pace knocks me into the Curio cabinet. A porcelain doll falls out of place but doesn’t break.

“I thought your parents weren’t coming back until Monday,” I say while searching for my underwear.

“They aren’t! Well, they weren’t. Can you put some fucking pants on please?”

“I’m trying to!”

We hear the front door open and footfalls followed by the squeaky wheel of a carry-on bag.

Henry pulls all the sheets off the bed and throws my panties at me. I pull them on and grab my pants from the floor. Henry haphazardly dresses his lower half before glaring at me and mouths for me to return his shirt. I lift it off and scramble for another. I reach down toward the mess of sheets and clothes and pull it on. Henry gestures for us to quietly exit, his face stern. He checks the hallway then nods for me to follow. He looks back at me, curls the fingers of his right hand and twists twice. I pull the door handle towards us and carefully shut it.

We walk downstairs and I see Henry’s father at the closet between the kitchen and the living room, hanging up his coat.

“Oh, hi Beth. Henry didn’t tell me you’d be here!”

“Beth was visiting her folks so I invited her over,” Henry interjects as he approaches his father to greet him with a kiss on the cheek. “It got late and she’d had a few so I told her to crash.”

I sit on the couch as Henry says this and wrap the blanket around my body to make it seem as if I’ve slept there.

“Sounds rational,” Henry’s father replies with a smile.

I have met Henry’s father on multiple occasions, he is always kind and inviting. He is warm towards me as if he were my own father, often telling me how happy he is that Henry has found a friend like me.

“You’re home early?” Henry manages to say.

“Ah yes, your mother wasn’t feeling well, and so we’ve returned.”

I have only met Henry’s mother through the words he tells me of her and brief mentions during his father’s visits to the city. “She prefers the suburbs,” Henry’s father once said, “she doesn’t like to go too far from home.” She lives only in my thoughts and presumptions; I do not even know what she looks like, the only name I know for her, mother.

Henry’s mother enters the living room and everything goes cold. She carries a chill with her, she cannot be separated from it. I wrap the blanket tighter around me. She gasps at the sight of me, reaching for her heart. Henry laughs to himself, amused by her reaction. I shoot him a look but he won’t catch my eyes.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to startle you.”

I begin to introduce myself, but Henry finishes the introduction.

“This is my friend, Beth. We went to school together. I told you about her, remember?”

Henry’s mother is tall and thin. Her cheekbones sit high and her cheeks sink in. Her hair is short and black like Henry’s, long enough to be tucked behind her ears. Her eyes are large and round, her eyes are Henry’s. She is wearing a magenta turtleneck, a gold necklace and black dress pants. When she moves her hand from her heart the rest of the necklace is revealed, and a golden letter B swings from the chain.

I have stood up to approach her and as I offer her my hand, the blanket falls from my shoulders. Mother’s eyes shift upwards from my offered hand and they remain there. What little expression she had, the small smile she was attempting to conjure vanishes as she stares into my chest. She turns her head away and places her hand to her mouth as if wiping something away but I can still see that her eyes are full with tears. She swallows hard and glides her fingertips over her eye hollows. Her face looks pale. I put my hand down slowly and instead nod, trying to offer some sort of grace with my body. This is the woman I laughed at.

“It’s really nice to meet you,” I offer while trying to swallow my guilt.

She tries to offer food, quickly turning and walking towards the kitchen. We follow. She pauses at the fridge and hangs onto its handle for too long. Henry’s father walks over to say something to her and announces that they are going to go out to breakfast, and we are welcome to join.

Henry declines on our behalf and I feel relieved because any appetite I had has been lost in this strange encounter. Their bags are still sitting by the doorway as Henry’s father returns to the closet to retrieve their coats. Henry walks with them towards the door while I watch from where I am. His father digs into his pockets and pulls his car keys out.

“Okay, we will see you when we get back. And in case we don’t, it was lovely to see you again, Beth.”

The door closes and only Henry and I remain. I turn and say,

“Your mother, she’s so…”

“Bitchy?” he says.

“No, she’s just…she feels like she must be so sad.”

We often tuck our sadness and fear into some hidden layers of our being. We cover them with extreme emotions; the fire of anger or the chill of indifference.

“Probably,” says Henry.

“Right, okay. Uh, we should probably wash those sheets before they get back,” I say.

This is when Henry realizes what we’ve done. His eyes move towards the stairs. He stares a little too long and I approach him, but before I can touch him, he pulls his shoulder back and away from my hand and heads down to the basement.

“I’ll meet you up there,” he says.

I walk upstairs to Bridget’s room. When Henry arrives, he is carrying an empty laundry basket. He pulls the sheets from the floor and bed and any garment soiled by the air.

“Take off your shirt,” he says.

“I don’t think now is really the…”

Henry cuts me off, to stop me from embarrassing myself.

“It’s hers. You’re wearing her shirt.”

I look down at the white t-shirt I have on with our high school logo and the word CAPTAIN beneath it. I pull it over my head and place it in the basket.

“I’m…I’m sorry, I didn’t realize…” I attempt as Henry exits the room.

While we wait for the bedding to finish, we vacuum the floor and rub lemon-scented cleaner into the headboard. We dust her dresser and shine the handles until they feel clean again. The hot sheets feel good, temporarily taking me away from this moment. Henry is stealthy and moves with focus separating the bed’s layers from each other. The thinnest sheet parachutes down onto the bed and we bury it beneath two blankets and the roses. I arrange the rabbits as best as I can remember. Henry rearranges them properly. I’m still holding the teddy bear. It reminds me of a viral video I once watched called “Teddy Gets An Operation.” The doctor cut open Teddy, bloated with white stuffing, and replaced the fear in his heart with curiosity.

I thought maybe our hallowed act would have conquered the somber stillness of her room. At the very least, it might have made everything feel a bit more human. Henry reaches into the Curio and picks up the fallen doll. He places her into her stand and pats down the top of her hair. He slides her glass catacomb shut then turns to me. He is looking at me and past me at the same time. We haven’t spoken the entire time, our silence weighing our glances down from each other’s eyes.

“She looks trapped,” I say.

“Hand me the Windex,” he replies.

Henry wipes his fingerprints away.

No matter how meticulous we are with the folds in the sheets, or how many corners we reach with our soiled cloths, the dust only flies into the room’s air and burrows deep into the carpet. Once our efforts are exhausted, Henry tells me I should probably go home. He says it in a way that implies I am no longer welcome. I start to say something, to search for the words to soothe him, to get him to let me stay but my body stops me and my throat warns me not to speak anymore. Just let it go. I leave the room and look back once I’ve stepped into the hallway. I inhale the scent of artificial lemon, something disguised as refreshing. I look at Henry, he is facing away from me, his body towards the outside with only this wood framed window in his way, the freshly cleaned glass reflecting his image and the entire room like a mirror.

◆

Art credit: “Bridget’s Bed” by Jim McKenzie