The miracles are brought to the zoo in three black crates held aloft by three forklifts. The crates are settled on a patch of yellow grass and the forklifts shuffle backward. Nobles leaving a throne room. A voice on the loudspeaker:

Lions have returned to America.

The four rounds of gastrointestinal surgery were a success. These lions are no longer reliant on meat but can survive on fermented soy and its associated products, just like the rest of us. God bless those hands that entered their stomachs and twisted their intestines into lace.

The crowd cheers. Richard doesn’t look up. He sits behind the counter of the zoo’s Subway and refreshes the American Psychiatric Association website while the robot takes the customers’ orders and serves them lunch.

The DSM-X is being published today, and Richard is feeling uncharacteristically hopeful. He tries not to indulge the hope though. Hope isn’t a symptom, or at least, it wasn’t in the DSM-IX.

I think your robot’s steaming, says a customer.

Not my robot, Richard replies, refreshing his browser again. Not my job.

Richard is the zoo’s only human employee. The robot cannot be ordered to defy its customer safety programming, so Richard is paid eight credits an hour to violate enough health codes to ensure Subway is still able to turn a profit despite the meat scarcity.

Sometimes he rewrites the expiration dates on the mayonnaise tubs. Sometimes he places the tempeh thermometer in a cup of boiling water before the robot does its reading. Today, he lets the robot steam, downloads the DSM-X on his phone, and reads the new disorders.

Virtual Reality Adjustment Disorder.

Obsessive-Compulsive Sleep Syndrome.

Nostalgic Personality Disorder.

Intermittent Despair.

Technosocial Communication Disorder, marked by inability and/or unwillingness to communicate effectively with mechanical assistants.

Do you think I am able to communicate effectively with you? Richard asks the robot.

I’m sorry. I don’t understand, the robot says, steaming.

Can I get a fuckin’ Baja Tofurkey Wrap over here? asks a customer.

None of these disorders feel quite right to Richard, but he doesn’t want to write them off before he has consulted with his psychiatrists. It’s a Sunday, so he’ll see his Freudian tomorrow. On Fridays, he sees his Jungian, and on Wednesdays, he sees his psychic. He hasn’t told any of his psychiatrists that he’s seeing someone else, but he figures that if the psychic was any good, she would know by now.

Richard is twenty-eight years old, and he has not yet found an explanation for his pain. His pain is unwieldy and inconvenient. It exhausts him.

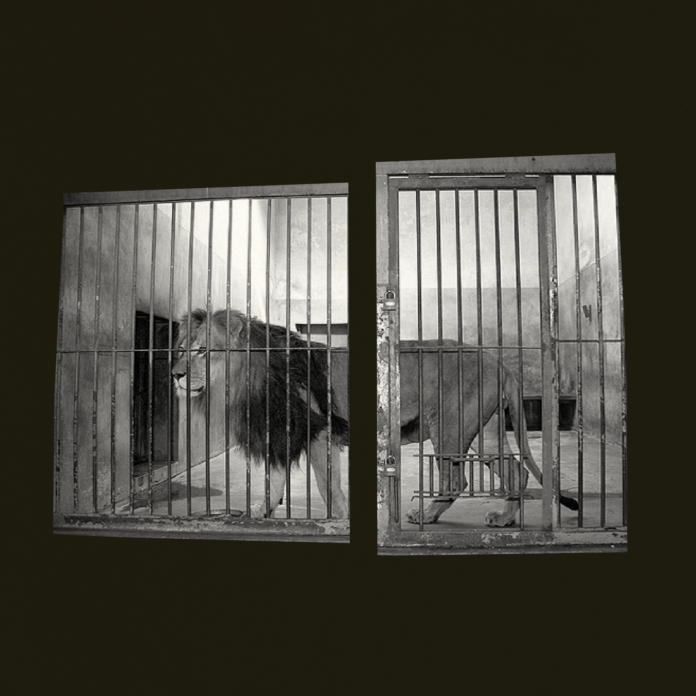

When all the visitors have gone home and Richard has powered down the robot, he walks by the lions. They are lying down in front of their crates, resting their heads on the dry earth. Their bodies look a little skinny, but not unhealthily so. Their manes blend into the grass.

At Richard’s session with his Freudian, he asks about the DSM updates.

Well, the Freudian says. It doesn’t look promising. They’ve added many new disorders, but they haven’t published much guidance on how to define your symptoms.

Isn’t depression a symptom yet?

Yes and no, the Freudian says. Depressive symptoms can only be diagnosed on someone with a Rank 6 productivity career or higher. Maybe try getting a promotion first?

Richard doesn’t want a promotion. He only applied to his current job because he thought working in customer service might help him develop a traumatic stress disorder. Maybe we can decide on a disorder and then work backwards?

The Freudian nods, sternly. His face is smooth like a ceramic plate. Richard wishes his Freudian had a beard. His old Freudian had a beard, which made him feel authentic, but he also demanded that they both strip and exchange clothes during each session. This Freudian is new.

Let’s talk about your childhood, the Freudian says. Were you sexually abused?

Is that usually the first thing you ask?

Not usually, the Freudian says. But you are a homosexual and you live with your mother.

I thought homosexuality was no longer classified as a mental disorder, Richard says.

It’s not, but it can be a symptom. And God knows, we could use one.

Well, I wasn’t, Richard says, churlishly, before adding, But I often have dreams in which I am having sex with my father.

The Freudian nods. That is very normal. Dreams don’t mean anything, you know.

Richard returns home this evening to his boyfriend, Charles, and his mother sitting in the kitchen. Charles is rereading a newspaper from thirty years ago. Richard’s mother is playing solitaire.

You are looking rather psychosexually afflicted these days, Richard’s mother says, looking up from her game.

Thank you, Mother.

Richard used to call his mother Mom, but he’s hoping the associative qualities of Mother will reveal some mental disturbance he can identify.

You are seeing Dr. Vaugn, aren’t you?

Yes, we just had our session today.

Richard’s mother shakes her head. It’s no use going to a Freudian once a week. You really need to see him three or four times a week, if not more, for it to work properly.

Charles shakes his head and smiles at Richard from behind his newspaper. He mouths: Don’t listen to her. Or maybe: Go fix the cooler. It’s difficult to tell what he’s mouthing through his British accent.

Charles is rich, but very cheap, which makes him a likely candidate for Anti-Economic Personality Disorder. Unfortunately, Charles doesn’t buy into the new psychiatric revival and considers medical science to be an enormous pyramid scheme, which is ironic because he works in finance. Instead of attending therapy, Charles smokes weed and pretends to meditate, and instead of paying rent on a one-bedroom apartment, they live with Richard’s mother in Richard’s childhood home. They have been dating for four years.

Richard looks at the newspaper Charles is holding. Everything with a price is defunct or scarce now. All the advertisements have become obituaries.

I wish you would be more supportive, Richard tells Charles as they are climbing into bed that night.

Are you still seeing that psychic I recommended? Charles asks.

Yes.

Good. Can you ask her to try to shift your aura away from teal? Maybe try forest green this time. I feel like we’re one of those couples who color-coordinates their clothes in photographs.

You wouldn’t be able to see our auras in a photograph, Richard says.

Yes, says Charles. But I would know.

In bed, Richard reads the DSM appendix regarding culturally specific disorders from countries outside the United States. It makes him feel like he’s on vacation. Maybe one day he can visit one of these places and experience its symptoms for himself.

Charles pulls the blanket over his head and sleeps.

The lions at the zoo haven’t been eating, so the veterinarian robots arrive with IV drip bags of white fluid. The robots hang the bags on the branches of a plastic marula tree that has to be carried in on a forklift. The fluid is viscous and has to be squeezed through the tubes by the robots’ delicate rubber hands. The lions are resting their heavy heads on the grass.

The loudspeaker repeats the same message through Richard’s entire shift.

Don’t worry, folks! The feedbags are entirely plant-based!

The psychic Charles recommended has an office above an Italian restaurant so everything smells like Synthetic Palo Santo and garlic. The room is entirely lit by candles. Richard and the psychic sit cross-legged on the rug opposite each other.

Richard is in pain. He is unable to define it. It is interfering with his life. Is it that he cannot define his pain or that he cannot define his life as a life worth saving from interference?

The psychic shushes him. You are thinking too loudly, Richard. Try to fill your mind with forest green.

The Jungian wants to talk about Richard’s father.

Let’s talk about your dead father.

Richard frowns. He is alive. I just don’t speak to him anymore.

He’s alive? The Jungian makes a note. Your father whom you cut out of your life, then.

I didn’t cut him out, Richard says. I just forgot to call him one week and then I felt too embarrassed to call again.

When did this happen?

Two years ago.

The Jungian makes another note. Tell me a childhood memory about your father.

My father would fall asleep watching television. He would fall asleep on the sofa, lying down, with his legs slightly bent so they made a triangle with the back of the sofa.

Alright.

When I was a child, I used to sit cross-legged in the space behind my father’s legs and lean back against the couch and pretend I was in an opera box.

An opera box.

I was an extravagant child with extravagant fantasies.

Wealth is a sanctuary to you, the Jungian remarks.

Isn’t it to everyone?

Only the wealthy.

Yes, of course, Richard says, blushing.

The Jungian makes a note.

Embarrassed, Richard says, Maybe wealth is a symptom of something?

The Jungian shakes her head.

A moment passes.

Well, is there anything you want to say?

What do you mean?

Why are you making me talk about this if you’re not going to analyze it? Or give me insight as to why it affects me? Why I am the way that I am?

And what are you?

That’s what I’m waiting for you to tell me. Apparently, the manual doesn’t cover it yet. I’m miserable. I’m in pain. I feel wretched. All those 20th-century words they used before they had a full psychiatric lexicon to describe their disorders. I feel it all.

Well, if that’s how you feel, then I can’t help you.

Richard falters.

Thank you for your honesty, he says. He leaves the session early.

When Richard returns home tonight, the kitchen is dark. Time glows on the microwave. His mother and Charles are usually here when he comes home from his psychotherapy.

He walks up the stairs, quietly. He has the peculiar feeling that there are people in the house, waiting in the dark, preparing to jump up and yell surprise. Any moment, he will turn a corner and remember that today is his birthday.

Richard reaches the top floor and no one appears. Soft sounds, like a kitten purring, emanating from the guest bedroom. His mother’s laugh. The smell of weed.

He considers knocking, but he is ultimately too embarrassed to interrupt the affair. This must be a symptom, he thinks. He leaves.

In the blue of the evening, it is a relief to experience the source of his pain. This moment, Richard decides, has been radiating backward in time. He has always felt this pain, and now he knows why. He feels like his heart is swallowing itself. Does the DSM-X cover pre-traumatic stress disorders? Around him, people walk in a wide berth. His heartbreak is finally acute enough to be contagious.

Richard does not know where to go, so he goes back to the zoo. He knows where all the cameras are and what their passcodes are.

He disables the alarms and enters the zoo compound. The zoo is surprisingly loud at night. All the nocturnal animals are jet lagged and annoyed.

Richard and his symptoms unlock the Subway, crawl under the counter, fall asleep.

Dawn breaks over Richard’s head like a 2×4. Eyes watering.

There are hours before any visitors arrive. Richard leaves the Subway. He walks through the morning to the lions’ enclosure. Yellow bodies on the yellow ground. The IV bags are gone and the lions are asleep. The sun drags its light through the tree’s plastic leaves. Richard is in pain. He hops the fence. He walks toward the lion. It is lying on its side. Mane shivering. Richard is in pain. The lion’s eyes are closed. Its eyelashes twitch in the wind.

Richard crawls into the space between the lion’s legs and its belly. He lies there until he dies.