The petroleum truck honked at him again on the I-90. Impossible to say if the driver intended to be friendly or hostile. It had a green cab and a sleek silver tank that glowed strangely in the fading sunlight. Reaching up to pull at the fraying chord of his own air horn, Jeb squinted at the license plate. Pennsylvania. Naturally. The highway was reflected in the other truck’s distended belly, with the cracked tar splitting off into the brown sky. It was almost night.

In the sleeper cab behind the driver’s seat, an empty liter of Diet Mountain Dew rattled around. Jeb groped blindly for the piss bottle before giving up. It was hour eleven anyway, and he was almost there. To distract himself from the burning in his bladder, he switched on an audiobook about naval spies. An agent was blowing up a casino in Panama while the ghostly trees of Ohio slipped by in spindly blurs. He lost track of the plot almost immediately as the narrator’s glossy voice blended into the ancient hum of the road. Sometimes, after a long multiday haul, he found the sound of real human voices disconcerting, almost grotesque. Over twenty years of driving, he’d grown reliant on the radio for daily conversation. His ears were habituated to its smooth, slick sentences.

Jeb liked driving more than almost anything. It was much better than flying, which he’d done only twice. His wife had loved it, seeing the cities glitter like a circuit board from above. But he preferred to gaze out at the open road and trace his journey on the map in his head, like a blood molecule running through the veins of the north. The boredom of it ended up killing some guys, his half-uncle, for example, who’d fallen asleep at the wheel and drove his semi off a bridge near Toledo. Two years ago now, or three. But Jeb liked to have an empty head. His greatest and only advantage in life was that he could live in the moment; this much he knew of himself. He didn’t turn over worries all day as his wife did, laundering them endlessly in her mind. “Some people got Velcro brains,” Josie once said, “but you got a mind like oil. Ain’t nothing that sticks.” She was assistant manager at one of the three Hardee’s around Xenia. Bad pay, worse fries. Every shift she found a new calamity to call him about, and usually she liked to cry too. She’d been crying when they first met, sobbing on the broken postbox by the Dollar Tree.

“Alligator on the 30,” came a crackling voice over the CB radio.

“Saw that about ten miles back. Evil Knievel up ahead.”

“Back it down, Swamp Fox. Don’t want to be bear bait.” That was Marjorie, another driver from Jeb’s company.

“42, Large Marge.”

A car swerved in front of the truck, a little red Hyundai with a faded Bush ‘04 bumper sticker stuck to its rear window. Easing on the brake, Jeb reached down and pulled at the compression socks he’d started wearing to negate the truck’s constant vibrations. The infinite pavement was starting to wear on him. His back had begun to ache chronically, enough for the freight company to cover a doctor’s visit and some pills. If the pain kept worsening, like a toothache in his spine, driving would be out of the question. And what then? Next week would be Jeb’s forty-fourth birthday. He’d begun to notice small, uninteresting developments. He could no longer read drive-through menus in the dark, except for Wendy’s, whose displays were back-lit with green LED. The dirty calendar his boss distributed every Christmas came out of the glove box less and less. March this year was a slender redhead lying cunt-open on a giant lily pad. Sexy but toad-like. Slightly off-putting.

The truck bounced over a low, decaying highway bridge. The sound of the burbling river below reminded him of how badly he had to piss. To distract himself, Jeb switched off the audiobook and scrolled through his phone to find an MC Hammer album. He didn’t need to take his eyes from the road, though he could have; the Hyundai that had cut him off was now driving ten below the speed limit. They passed an overturned minivan in the center lane, its grey carcass glimmering in the encroaching darkness. Several ambulances were lined up in front of it, like a wailing tribunal. Jeb picked up the radio:

“Big Bunny here. Watch out near the Elida exit, there’s a car gone greasy side up.”

“10-4, Big Bunny.”

“10, preeshaydit.”

Jeb adjusted his belly so it didn’t interfere with the wheel’s rotation. That’s why his CB handle was Big Bunny; Jeb was buck-toothed and big-bodied, with just a little too much fur on him. He pushed another layer of lipid up towards the window. Most people he knew were always trying to lose weight, except himself. His wife had taken to carrying Splenda in her purse, squirreling away the little pastel packets from diners and sucking on them at timed intervals throughout the day. She was always trying to feed him her rabbit food, making dinners of lettuce and not much else. Still she lost no weight. Josie added it up once and as a pair they weighed just short of seven hundred pounds. Jeb didn’t care one way or the other, though now he always checked an elevator’s weight limit if he came across one.

On the left, a series of billboards slipped by:

Curious about eternal salvation?

855-FOR-TRUTH

Come to MCDONALDS! I’m lovin’ it.

[next exit]

Derry’s Discount Family Dentistry

A great smile changes everything. ☺

(419)-MY-TOOTH

His exit was in thirty miles. He was headed to stay with Noelle, though he could have made it back to Xenia if he’d booked it. Back to Josie. But he liked to stretch this leg of the trip out, ensuring he had to stop short of home. DOT regulations were strict about driving too many hours anyway. Can’t have drivers getting sleepy and careening all over the place, especially in the ugly rustbelt winters. Black ice liked to hide in the bruised yellow snow. Turn into the slide and you might survive. Sometimes he dreamed about ending up upside down with the glittering roadside litter. In any case, the next drop and hook wasn’t scheduled until tomorrow. The boys would need at least a day to preload the trailer.

Most of the time Jeb hauled stacks of pristine printer paper for commercial distribution. Worth more than you’d think. Sometimes he thought about prying open the packages and scribbling on random sheets. He would trace out patterns in black ink like the entropic squiggles of tar that mended the fissures in the asphalt. And the ruined white leaves would be carried out into the world.

Power lines sliced apart the dark sky and a yellow diamond announced that he was entering a fog area. Thirty-five minutes away, give or take. Jeb marked his time in road signs. Noelle didn’t cook, but she would be waiting for him with the trailer all tidied up for his arrival. Ready to trade love and drugs. He came by two or three times a month, whenever there was a load going up to Toronto. She wasn’t better than his wife, just different. When he’d met her at a rest stop, he’d mistaken her for a Road Juliet. He wasn’t the type to proposition those sorts, but he’d noticed the leggings she wore, tight and black like a second skin. When he’d offered her a spare dollar for fries, they’d gotten to talking and Jeb recognized her voice immediately. Noelle was a dispatcher for the regional trucking company. She spoke in a lyrical rasp, with a kind of coy authority that charmed him. He’d always thought of marble sculptures when he heard her voice, Greek ones, naked and untouchable. He’d suspected that she was sweet on him, always giving him the best routes and warning him of even mild weather disruptions.

“The ice is as slick as a snake,” she would tell him, “you be careful, Big Bunny.” Whereas any other dispatcher: “Ice ahead.”

Noelle had been a museum bust directing him through the radio waves. But she was much better in the flesh. At their first meeting, he learned that she loved to watch the autumn leaves change, when the bright spurts of green would come to resemble copper and gold pennies in a matter of days. As a child, she’d made clothes for fairies out of the first orange leaves. Did he believe in magic as a boy? They talked for an hour, then two. Jeb loved how she clucked while she ate, like a fat chicken. A sound of honest pleasure. He’d offered to buy her an ice cream just to keep talking, to hear that contented noise again. Had she accepted, it would have made her the second woman he’d ever been out on a date with.

“I don’t much like ice cream,” she’d explained. “I get that brain frizz, when the cold hits the roof of your mouth and it makes your head get sharp-fuzzy for a second.”

“So that’s no?” he’d asked.

“No,” she’d said, smiling big to confuse him. And on the bench near the diesel pumps, in the hard September breeze, Jeb had decided right then that he could love her.

A soft rain began to splatter across the windshield. He made bets with himself about which droplets would shimmy down the window fastest and lost every time. The red Hyundai turned into a crumbling Seneca liquor store. There were large crinkled signs in the store windows advertising BEER AND REDEMPTION. Jeb honked goodbye to the driver with jolly hostility, tires squelching in the wet. He knew the rain would continue. The gangrenous clouds were fat and hollow.

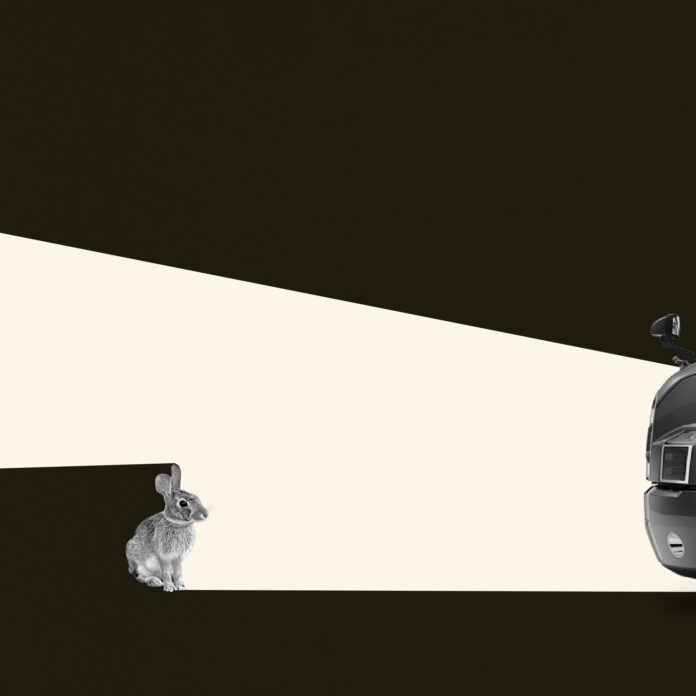

Six miles later, a giant dark figure darted across the road. Then another; the night rabbits were back. The first one had appeared a little over a year ago. During an overnight haul to Buffalo, an enormous rabbit had materialized in the middle of the road. It had hopped down the golden centerline at a leisurely pace, dissipating into shadow as the truck ran through its silky flank. Jeb had slammed on the brakes, terrified and half-asleep, his front bumper nicking a snowbank. He was convinced he’d run into another vehicle, or a rolling boulder, and he braced himself for a delayed impact that never came. When the truck continued to barrel forward unimpeded, he’d pulled off onto the shoulder until he could breathe again. The distorted vectors of his high beams had revealed nothing. The grill was unscratched and bare of guts, so he’d taken an aspirin and kept going.

The night rabbits followed Jeb from then on, emerging out of nowhere onto the pavement like nighttime patrolmen. Only visible after dusk, they were creatures of shadow. Size of a horse. They came and went as they pleased. At first the rabbits appeared rarely and usually in the distance, little more than tricks of the light. But lately they’d been getting closer and closer to his truck, their bodies almost brushing against the spiraling tires. Slowly and steadily the animals approached. One day they would no longer be on the outside of the truck.

After the rabbits’ fourth or fifth appearance, Jeb had allowed himself to worry. An acidic feeling came over him as he watched them hop down the empty expressways. Enormity aside, prey animals shouldn’t approach humans; it was unnatural. And nobody else ever seemed to see them. A couple of men at the truck stops spoke of similar encounters. One tanker driver even talked with his dead best friend on the road, claiming they had long conversations about movie releases. Rabbit or ghost—after a while, the road starts playing games with you.

Unsettled by rabbits and about ready to piss himself, Jeb hit the brakes and pulled his rig into the gas station parking lot. It was a quarter past seven and the deep grey night was leaking out behind the storm. He took cover in the sturdy shadow of his truck and emptied himself out onto the yolk-yellow curb. The urine looked the same as the rain. He liked to void himself after a long stretch of driving. It felt good and easy. Zipping up his fly, his eyes were drawn to the dim glow of Bertha’s Diner. He thought of those first fries he had bought for Noelle and, knowing her cabinets would be sparsely stocked with canned soup, hustled across the street. The Exxon floodlights spilled across the cement like soapy mop water.

The diner was mostly empty, its red stools vacant except for a young man sitting slouched against the counter. Jeb counted twelve handwritten signs advertising video security. Each warning was accompanied by a poorly drawn skull and crossbones. The only other décor was a collection of unframed posters of different national parks. Since his last visit, Yosemite’s waterfalls had started to curl off their wall. The cook cleared his throat to get Jeb’s attention, waving the spatula lazily in his direction.

“A #2 and a #7, extra pickles. Two pops. To-go.”

The cook nodded, his skinny dreadlocks swinging close to the grill. Oil sputtered up into the air and onto his bare dark arms, but he didn’t seem to notice.

“Go on and take a seat,” called the waitress as she retied her apron. Jeb stayed standing, leaning against the abandoned hostess stand and drumming his fingers across a sticky dessert menu. He instinctively avoided touching the picture of the pecan pie, as he was allergic. Across from him, an old man was sitting in a booth with a young child. Both had their eyes fixed on the technicolor television in the corner.

“You like wolves, kid?” the old man asked. There was a news program talking about recent wolf sightings near the local middle school. The anchor could not have looked less sober if he’d tried, careening as he was around the green screen.

“They’re my second favorite apex predator,” said the child, adjusting his glasses. He began to draw purple circles on a paper placemat. “After the killer whale.”

Jeb looked down at his phone while the waitress made her way over to him. A few notifications from his trucking app. A voicemail from his doctor; he decided not to listen to it. Josie had sent him an upside-down smiley face. Whatever the hell that meant. She’d been suspicious lately, holding him in the corner of her eye, asking after his routes. Unsettling. Before he’d left for this haul, she had begun wearing an angry face and blue lingerie around the house.

“Can I get milk instead? I don’t want to taste people,” said the boy.

“You won’t taste no goddamn people,” the old man snapped.

“But Billy said about the accident. He said about the accident that you can still taste ‘em in the water.”

“Billy don’t know shit.” He rattled the boy’s glass with a gnarled blue hand, shaking it so hard that ice cubes fell out onto the table. “Now drink up if you thirsty.”

“I wish I was a wolf,” said the boy. “Then eating people wouldn’t be bad.”

“What’re they talking about?” Jeb asked the waitress, whose nametag read Coral in bubbly letters. She had on glittering lavender lipstick that leaked down her pale chin. Pretty girl. Thin as a plumbing pipe.

“Aw, it ain’t nothing.”

“Don’t sound like nothing.”

“Well, it ain’t nothing now, anyway. Around ten years back some kids got stuck up in the water tower, went swimming up there on a dare or something.”

“That all?”

“I guess they couldn’t get back out.”

“What happened?”

“Well, they drowned. Everybody figured they took off somewhere, but their bodies ended up rotting in the tank for weeks. Poisoning the water and nobody knew.”

“Is that a true thing?”

“My cousin said when the county finally pulled them out, they looked like fish monsters. She knew one of the boys. And they got all fat in there. His mama howled for weeks.”

“No shit.”

“Yeah. We don’t talk so much about it, but most people in this town got some part of those kids inside of them now. At least a few bits from the shower or the tap.” She put down his water and went away to deliver an order of eggs to the slumping man at the counter.

Jeb turned toward the window and squinted past his reflection, sullen and translucent. As a kid, he’d believed that his reflection was his soul following him around. The downpour made the surrounding mountains swell and flicker like images lost in television static. He looked for the rusty sphere of the water tower poking out of the trees. It must have been terribly dark in there. Slimy. Inside the diner, the light was warm and honey yellow.

“These chicks ain’t right,” said the man at the counter. “I said scrambled, not over-easing.”

The waitress smacked her lips together with a bright sound. The easy way she moved made Jeb feel old, like water in a down-sloping creek. Across the road, a bobtail truck pulled into the Exxon station. A figure in an orange turban slid out, the color flickering like a flame in the rain.

Coral kept talking as she pretended to wipe down different tables. “You know, I always used to mess up that expression, not to have all your eggs in one basket. My gram used to say that a lot. Like to explain why she got different kinds of lottery tickets. But I always thought she said casket. Like, for years. I used to think that when somebody died you put an egg into their casket for good luck or something.”

She laughed, a clean high sound, like the smell of Lysol, as she brought over Jeb’s order in a stained paper bag. The diner door shut softly as the other driver entered. His t-shirt read No Jake Brakes! in ironic font.

“Armeet!” Coral called. “Slice of coconut cream?”

Jeb traded the waitress a handful of cash and exited the restaurant, nodding at the other trucker as he did so. The ring of light around the moon looked like an oil spill. He climbed into his seat and started the engine, waiting for the seatbelt alarm to tucker itself out as the smell of salty grease crowded the truck. Jeb had never met a driver who wore a seatbelt.

The rain was coming down harder now. No streetlights. He sighed. Driving through Noelle’s little hometown, the world looked broken and unlit. Didn’t have a Walmart for fifty miles. But it still felt familiar, entirely navigable, with its 24-hour Arby’s and Buttle Boulevard and the magnolia tree next to the Episcopal church. Jeb reached into the bag and pulled out a fistful of French fries. He ate them one by one, long fries first, like he was picking straws.

Just as the road met the old train tracks, a darkness slinked suddenly into his peripheral vision. Then a swathe of black fur brushed over the windshield, obscuring his view of the road. Jeb swore and blinked feverishly, his foot easing down on the brake as he guided the steering wheel left, towards where he thought the next curve in the road would be.

The leaping mass seemed to hover in front of the window for several long moments. He felt one of the rear tires meet grass, and then a front wheel started spitting gravel from the shoulder. There was no way to tell where he was going. If he slammed on the brakes any harder, at least one of the duals would lock up. The truck bounced and rattled. A low keening noise leapt from his throat.

Then the creature was gone, and the road rose grey and straight before him. He yanked the wheel until the course was corrected. His foot remained on the brake, feathering it feverishly even after the truck came to a stop. His breath had left him, and the air around him was chilly and thick as if he were underwater. The fries in his fist had turned to mashed potatoes.

“Dagnabbit, rabbit!” Jeb yelled into the cab. He flipped on his hazards and pounded his fist into his door until the ache in his fingers calmed him. Lucky that nobody had seen that. It was difficult to make sense of the rabbits, what they wanted. He had to drive them away, before they got to him for good, but he had no idea how he might do it. Now they were nowhere in sight. Jeb flipped the engine off and sat for what felt like a while. Eventually, the potatoes between his fingers got flakey and cold and his mind turned to Noelle. He flipped on the engine and his high beams and, after a pause, relocked the doors.

Oceanview Park was only a few miles down the road. The night rabbits reappeared to trail him from a distance, their silhouettes flickering in the side mirrors. Objects are closer than they appear. Jeb blinked hard. When they first showed up, he would close his eyes and the herd would vanish, but now when he opened them the rabbits remained.

He swerved around the trailer park’s rotting welcome arch. The dirt parking lot was big enough to park his rig in without too much trouble. As he lined up his drive axles, Jeb gave a short honk in greeting to one of Noelle’s neighbors who was walking up the road with a pregnant Speedway bag bouncing from his withered limbs. Jeb rolled down the driver’s window.

“How’re you doing, John?”

“Oh, fine. My stomachs are acting up but what’s to be done. Sometimes you just get old, you know?”

“Sure do.”

“Well, you’re gonna know soon enough, let me tell you. One day you wake up and look in the mirror, all set to see that handsome mug you’ve known your whole life, and instead you’re looking at a bear’s wrinkled ass.”

“You’re an ass, that’s for sure,” he said, smiling down towards John.

“Oh, go to hell. What I got is a dead dick and six grandkids. Time won’t stop for no man.”

“I’m learnin’ it.”

“You, me, even the land out here is learning it. At some point things start going down the hill and don’t get going up again. Did Noelle tell you they’re talking about selling this place? People have already started leaving, looking for greener pastors.”

John waved cheerfully as he staggered between the rows of trailers and disappeared. Where would he go, Jeb wondered, if they closed down the park? And Noelle—where would she go? She hadn’t mentioned anything about the park getting sold. In any case, John was right; the county was clearing out, and even bigger towns like Xenia had more empty homes, windows boarded up or broken. The only time Jeb saw a crowd anymore was for the city’s annual amateur radio convention.

He set the brakes and put the engine in neutral. When he climbed out of the truck, his joints creaked like a rocking chair. He tried to squeeze any lingering gas out of his stomach. From the sleeper cab, he extracted his emaciated overnight bag. Two bouquets were laid out across the bed. The yellow daffodils were for Josie, to remind her of his love. He picked up the pink tulips, which were for Noelle. Jeb had bought them at a small roadside stand right near the Canadian border. You had to know where it was, otherwise you couldn’t slow down in time for it. The vendor was a sweet old woman who always gave him a good price, though he could never remember her name. It was something foreign. He made sure that both the can and the trailer were locked down.

He walked past the shuttered management office, itself an ancient mobile home. It had a small garden out front filled with dog shit and violets. Jeb removed his camouflage cap and ran his wet fingers carefully through his hair as he approached Noelle’s singlewide. It was one of the nicer ones, and she’d brightened it up by lining the perimeter with pinwheels, flowerpots, and plastic flamingoes. There were even a few grinning garden gnomes, all of whom seemed capable of great violence. A dead basil plant stood between two plastic chairs where they sat in the nicer months to smoke. To the left was the small fence he’d built for her tomatoes. In a tin can between the chairs, a baby blue pack of cigarettes sat empty. Camels. Not his brand, and definitely not Noelle’s. He wondered if she’d left the box there on purpose.

She was at the door before he had reached the cement stoop. Thunder croaked overhead. Her eyeshadow was pale blue, the color of a robin’s egg. They kissed with private enthusiasm. Jeb hoped he didn’t smell bad, since he’d forgotten to pick up new cologne from Walgreens. Noelle beamed when he handed her the flowers. He followed her into the building, ducking to avoid the low doorframe. The house looked the same as ever—tidy, claustrophobic, everything different shades of peach.

“You brought a sweater, right? You know these trailers don’t heat good.”

“I did.”

“You need a shower or the rain got you cleaned off?”

“Yeah, I’ll take one real quick.”

“Don’t be long now.”

He washed quickly, only one half of his body fitting into the shower at a time. The smell of her rose-melon bodywash was sweetly familiar. He toweled off the water that clung to his beard and stepped tiredly out of the bathroom, dressed in his favorite blue sweatpants. It was raining so hard it sounded as if the sky was dripping barbiturates. He heard Noelle crack a beer for him in the kitchen and punch a time into the microwave. Her black cat, Choo, slipped between his ankles and yawned.

When he sidestepped into the living room, a baggie of shriveled green heads was waiting for him on the coffee table. He held the grimy Ziploc and extracted some cash from his wallet to put in its place. A nice white blank feeling settled over him as soon as the drugs were cupped in his palm. He tucked them carefully into his bag.

Noelle’s secondary income mostly came from dealing weed and speed to the younger truckers, the ones who already knew or didn’t care whether the company’s random drug tests were a farce. Neither of them liked to dwell on the transactional part of their relationship. Jeb liked to smoke on the weekends, and she needed the cash. Plus her brother was a pillbilly, so she had a constant supply. Both of them agreed that the business should be kept as separate from their love as possible. Recently, though, she’d been shorting him—not enough for him to bring it up, but enough to make him wonder just a little. He’d weigh the buds with Josie’s kitchen scale next day.

“What’s got you thinking?” Noelle called from the miniature kitchen. “I’m hungry.”

“Truck. Something’s up with my steer axels.” Jeb lumbered into the kitchen and sank down into the one of the white metal chairs.

“How was your day?”

“Alright. Had to pull a double yesterday, but other than that.”

“I got some dexies under the counter there if you want some.”

“I’ll stick with mini-thins for now.”

“You always do. Like all the Sikhs. They could drive twenty-four hours straight and never take a pop.”

“A lot of them got their own rigs. I wish I’d never sold. The company’s been a nightmare. Did you hear they renewed the Tyson contract?”

“You won’t be the one hauling the chicken shits away.”

“Not for now.”

“Your beard’s gotten longer, buttercup.”

“You like it?”

“I do. My forest man. My truck-driving big furry forest man.”

“I’m glad to see you.”

“I missed you. I wish you’d just come and stay with me here.” She didn’t understand that his absence was why she loved him. Their interest in one another was founded in a strange blend of comfort and novelty. Jeb knew that the distance was what made them real lovers.

“It’s special this way,” was all he could say.

“Well. How’s old Josie?” The way Noelle talked about Josie made it seem like they were friends. Maybe she thought they were. Jeb believed they would get along well.

“She’s good. Good. Her nephew’s started speaking, so she’s all giddy about that.”

“Do you think it’s right to have kids these days?” Noelle liked these sorts of moral problems. A woman is rolled into the emergency room wearing a t-shirt that says DNR. There’s a 1% chance that the rapist is innocent. Choose a child to kill or both will die. Jeb thought she liked these problems because it made her own circumstances more attractive.

“Don’t matter since I didn’t.” He cut into his cheeseburger, opening up the bun to ensure they added the extra pickles. Sure enough, seven bright emerald slices of dill. Noelle brought her sandwich to her mouth and clucked contentedly.

“I like that about you. I ain’t ever wanted kids, either. Too much work, and they always end up hating you. But now you don’t hate your parents.”

“No,” said Jeb, “but I ain’t love them that much, either.”

“I got good parents, you know that,” said Noelle, “but I’ve had three kids taken out of me.”

“Are you sorry?”

“Why would I be? This ain’t no place for kids.”

“I thought you was Christian.”

“Who said that, Jeb?”

“Then why you got all those crosses? Isn’t that why you’ve got them?” He pointed to a sparkling silver cross hanging on the cupboard. A muscle in his back pinched sharply at the movement.

“I guess so. Sometimes I can’t tell myself. I thought you didn’t believe in that?”

“I don’t, not really.”

“Not really?”

“I used to. My mother used to take us to church. There was this one time, I was maybe in third grade. A kid in my neighborhood cut open a dead sparrow on a dare and stuck his tongue into it. His lips dripped red when he took it out. Like rubies. It was the worst thing I’ve ever seen. The kid was smiling, too. I’ll never forget it.”

“That boy sounds crazy as cat shit.”

“And then a small tornado came into the town right after that. Two days later, no warning or anything, took us all by surprise. I was convinced that it was divine punishment. My mother said that was just the way of things—tornadoes coming right out of the blues. But I thought it was God.”

“But you don’t now?”

“Not really.”

“Good thing, since you won’t marry me.”

Both of them laughed, and the sounds harmonized strangely. Jeb played a slow piano song on his phone, putting it into a cup to amplify the sound. Noelle came to him and they began to sway awkwardly around the little kitchen, moving back and forth across the same couple of feet. Jeb flicked the light off so that they were guided only by the rhythm and the green glow of the electric clock. His hand fit well across the small of her back. He spun her in tight, slow circles until she got dizzy and pressed her face into his chest like a child. Water bounced violently off the windows. For a moment, Jeb made pretend that they were out alone at sea. As they rocked back and forth in the darkness, he thought of all the bulbs they had planted in the soil outside.

“I heard something strange about the water tower today,” he said when the song was finished.

“Oh, that,” said Noelle.

“It’s real?”

“Oh, sure. They cleaned it out real good, though.”

“Sad story.”

“That’s every story, buttercup.”

As she disposed of the takeout, he settled into the thin double bed. He watched through half-lidded eyes as the rain crashed down around the singlewide and ran his fingers over the blue floral sheets. He felt the kind of coziness you find yourself needing when you’ve just climbed out of a cold lake, bare and shivering in the air. Feeling sleep tug at his lashes, Jeb shook himself and switched on the satellite television. He turned to a program called Gotcha!, a popular prank show now on its fifth season. It was one of his and Josie’s favorites. They liked to smoke a joint together and watch the back-to-back episodes every Wednesday, when they had to babysit her sister’s kids. When she wasn’t on a diet, he’d order a Pizza Hut Big Dinner Box ™ to split. The last time they’d done that, Jeb had spotted a regular, real-sized rabbit on the lawn. He’d startled so fiercely he broke his sister-in-law’s recliner. “What is it?” Josie had asked, over and over, until Jeb just shook his head and turned up the volume.

Gotcha! covered every sort of prank in the book—jump scares, practical jokes, elaborate conspiracy theories. Every week a random person would be lured in off the streets of some west coast metropolis to be syndicated and humiliated. Instead of a laugh track, the show had the hosts giggling in the background, which made it feel more authentic to Jeb. He liked being in on the joke. His favorite segments were the scary ones, right when the victims first got spooked. Just before they began appealing to some divinity—“Oh god, no” or “holy shit, shit, shit”—something true and beautiful came across their face. Immediate. Maybe terror. He wished he could feel something that real.

“I hate these veins that keep creeping up,” Noelle said, gesturing at the navy lines winding up her thighs. She tugged her yellow nightgown down.

“I think they look pretty,” said Jeb. “Like hot lightning.”

She smiled. The television hummed and flickered. The producers were installing a Bloody Mary sex doll in a closet as part of a free home renovation. Out against the darkness, right near where his truck was parked, Jeb saw a watery silhouette. A trash can, maybe. Or a giant cottontail.

“What if you think it’s a prank and it ain’t?” she asked after a while.

“What are you saying now?”

The neighboring trailer was also watching the show, but they were delayed a few seconds. Jeb felt a small satisfaction that he would know first how the victim reacted, whether the fright left them angry or amused or occasionally unconscious.

“Like if I came home and found a ghost in the closet, my first thought would be that I’m on TV. Because of this show.”

“Well who’d the ghost be?”

“I don’t know. The water tower kids. My daddy.”

“I thought your daddy was dead.”

“Exactly.”

“How’d he go again?”

“Bad liver.” Jeb stroked the top of her hair in sympathy. She smelled like powdered roses, and he leaned his nose down into her skull to get a better whiff.

“Do you ever see stuff that’s not real?” he asked into her thin curls.

“I was just kidding about the ghosts.”

“No, I know. But sometimes I see things on the road that can’t really be there. Rabbits.”

“All of you truckers do. You should hear the calls I get, monster-this and Jesus-that. It’s part of the deal.”

“You think so?”

“Sure. It’s like this guy Phil. He sees cops in his rearview all the time, but they’re never really there. Like a desert mirage.”

“Is Phil the guy who smokes Camels?”

“Don’t get started with that. You leave me alone for most of the month and I’ve got to make dues with what I can. You come on back and I’ll kick him right out.”

“How long has Camels been coming around?”

“Long enough.”

“He here more than me?”

“He ain’t here now.”

His chest ached wet and tight and he felt a surge of tender dread. It was the same feeling he got, to varying degrees, when he was about to reach the end of anything—high school, a tv show, a bright bag of Funyuns. When his mother first got sick he’d felt it, and when Josie mentioned menopause. But more and more now this hazy, premature grief lingered, causeless, as if he himself was the precipitant. Jeb huffed out a hot breath, trying to shake himself loose of it.

“You gonna go with Camels when they sell the trailer park?” he asked.

“Who told you about that? So far as I know, that’s all talk.”

“It’s all talk until it isn’t.”

“Then say whatever the hell it is you want to say.”

“Why’ve you been shorting me?” he asked, after a pause. He crumpled the baggy in his pocket. Jeb knew he had other, truer questions but he couldn’t think of what they were.

“Is that what this is about?”

“Sure it is.”

“Then I ain’t been shorting you.” She spoke with resigned rigidity. When she looked away, he couldn’t catch her eye again. “You want me to pull the scale out?”

“No.”

“Because I can get it right now, here, it’s right under—”

“Dammit, I said it’s fine.”

“Oh, is that what you wanted to say? That it’s fine?”

“Is it fine, Noelle?”

“Tonight it is,” she said, and her voice, though gruff with anger, had a begging quality.

His phone started to hum, Josie’s ringtone, Cinnamon Girl. Had he told her he’d be back tonight? Jeb declined the call, a decision he knew he would have to answer for soon. After a moment, a text arrived: a series of upside-down smiley faces.

“Who’s shorting who, now?” asked Noelle as the song cut off. She was staring out at the trees, watching the rain feed the black puddles in her yard. She turned and smiled softly at him. For a moment, he was overcome by a terrible certainty that this would be the last really good moment of his life. It was a cold feeling, cold as any state winter on record. It poked and swelled in his chest, clogged his airway. Jeb wondered if this was how his uncle had felt as he drove off the bridge, if he’d woken up as the cab began to plummet or only when it hit the frozen water.

“Says he’ll take me down south, somewhere warm,” Noelle said.

“By the water?”

“If I’m lucky,” she said. “But don’t you worry. I’m not lucky very often.”

“I wish I could give you that.”

“No, you don’t.”

“He’s given you his word on this?”

“Sure he has,” she snorted. “Don’t get all bothered, buttercup. It’s all talk until it ain’t.”

Jeb pulled in breaths that would not go far enough down in his throat. He lit a cigarette, at least a temporary solution, and watched the white smoke curdle and bloom. The scent of his own tobacco calmed him as it settled over the trailer, seeping into its pale linens. Noelle leaned over to take a drag from the butt. As they watched the storm, he tried not to look for flashes of movement in the thin woods.

“But the rabbits—you don’t think I’m crazy?” he asked her.

“Not if you’re asking.”

“What do you think they mean? The visions? What do other guys see?”

“Some of them call in crashes that aren’t real when they get tired or, like, getting chased by bats when they’ve taken too much speed. I think it’s just them seeing what they’re afraid of, to be honest. Or sometimes what they really want. Like they see a sexy angel floating above them or something.”

“Good thing I got one right here,” said Jeb, pulling her to him. Choo hopped up onto the bed and stretched out across his ankles. Her fur felt like a handyman’s paint brush. These were the gold-tinged moments he lived for, Jeb thought. Doesn’t get much better than this. Not really. To think harder about it would be to ruin it.

The prank was a great success. When the credits began to roll, Jeb felt the dread bubble up again in his guts. Atomic, tremulous. He pushed the feeling back somewhere deep, though he knew it wouldn’t stay there long. The program changed to a police procedural and Noelle nuzzled into him. The detectives were investigating a murder committed with a bronze candelabra.

“I want one of them,” said Noelle.

“I don’t think anybody in the rustbelt has ever owned a candelabra.”

“We could be the first.”

They held hands for a moment, just leaning into one another’s fragile warmth. Noelle rolled a cigarette with the last page of a cheap romance novel, smoking the ink into oblivion. The rain pounded on. Eventually she made a move to mount him, the night rabbits watching from the window.