I was introduced to the beautiful and interesting people by a friend who was dating one of them. He and I were at the park under the bright frisbees and the distant planes and the general air of the power of late youth in a wizened empire eating barbecue chips and watermelon we’d somehow cut with a disposable knife and drinking rum wrapped in a black plastic bag. He told me this girl he was seeing was on her way.

I asked to see her social media. He said they’d met the month before on a dating app. I asked again. He said why did I want to see her picture: she was about to be here in person. I felt I must stand my ground on the issue and explained that it wasn’t the same, a profile was a self-portrait, not a selfie, and so on, and he relented in the hopes that I’d be less annoying. I observed that she was attractive. He affirmed me.

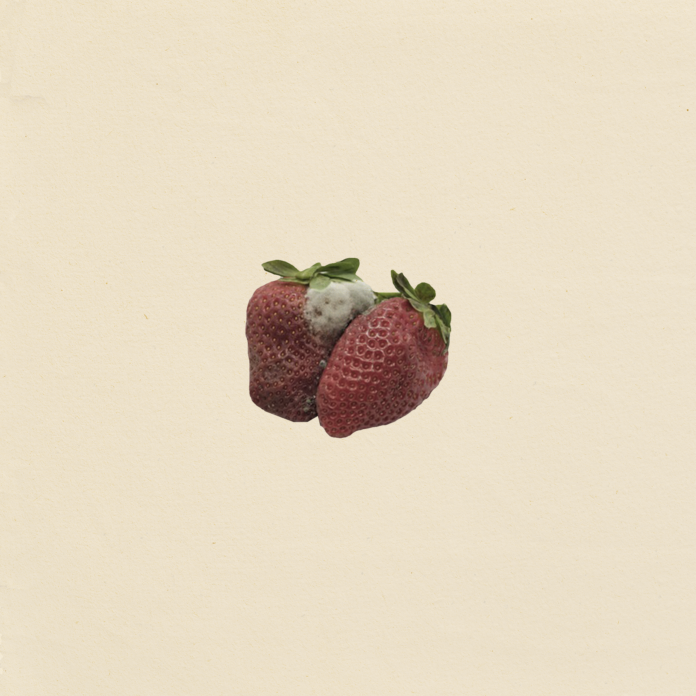

And then I pointed her out across the lawn as she stepped around a ruins of sculpted laughing shirtless men. Her white sundress with its red print of strawberries sailing over cream sneakers that alluded to chucks but were not chucks. I wore chucks. I shivered with indignation. What was wrong with chucks, an American classic after all? She held the brim of an extravagant white hat in one hand and in the other a narrow brown paper bag from a wine store. A vision from a Victorian lawn, she looked so at home here. She didn’t wave or smile as she neared; she kept her mouth closed, regarded us seriously, and then looked to the left and right at others.

My friend rose to meet her, and they kissed as I rearranged groceries and possessions to make room on the charming checkered blanket I’d brought from my apartment. My shoes weighed down two of its corners, tote another, wallet and keys the last. This may not have been wise, but it was what I’d done. She considered these objects as she descended. Finally, once all were on the same plane, he said this is Jean. I squeezed her (elegantly) limp hand.

This was the first time she’d looked at me. Now announced, she was warm, chatty, asked where I lived, told me about the guy at the store who’d insisted she buy a sparkling white, not a sparkling red, when she’d been craving a sparkling red since waking up, and had been drinking it all night actually, yet she had to listen to this guy’s whole take on the trend. And at the end of all of it, he’d snuck his number onto the receipt.

My friend held hands with the grass. I guess I should say his name was Mark. Mark leaned back on his palms. He thought she’d wanted a calm night last night, he said. I warmed to the friction. I loved him when he was indignant. He was his best, maybe truest, self when he felt he’d been wronged. That’s why I was such an asshole to him. My gift.

As she opened the wine, she explained with some sternness that she’d tried to go to bed like immediately after dinner. She’d been streaming this reality show where everyone’s naked in an ideal place. But the little subwoofer that could and the people her roommate was hosting were audible even through her noise-canceling headphones, so she’d said fuck it, donned an outfit she’d bought earlier that day, and joined those doing coke on the (orange, I’d soon learn) couch outside her bedroom. In fact, she’d just woken up an hour ago.

Mark said that sounded like a fun night.

I agreed.

She talked, and I watched Mark not watch her and savor his own sour time, which I knew he’d get over soon because he always did, and then I looked openly at her, and she seemed not to notice at all, so I just enjoyed seeing and being seen with an alarmingly attractive young person in my company. The day had changed when she’d sat down. Others sipped and chugged us. Those entering the park, a student with a buzzed head and a Russian novel and a green notebook, for instance, settled nearby. Mark and I were more beautiful, because we were more enviable, next to her.

The white dregs of clouds never clumped in the sky, and the late sun was so bright those without sunglasses saluted constantly. I was in a commercial for my life, which was the same life as those around me. I was in a commercial for our life.

“It’s such a nice day,” I declared.

She scrunched her eyes through the amber of her sunglasses.

“For sure,” she said.

We waited for Mark to agree. He did.

It was settled then: a nice day.

“Jean,” I asked, “will you hand me that?”

Our hands pecked as she passed me the bagged rum. I let its angularity and unpleasantness delightfully poison my afternoon. I returned it, and, to her credit, she followed suit, and Mark did, too, and then he was in high spirits again because we were a team.

And then we flocked along the path as we formed and deformed, letting runners and bikers split us before resuming the line. I told them I was hungry. They ignored me. A tiny leashless dog sprinted as though chased by foxes. Three hairy shirtless men shouted at each other in post-apocalyptic English, laughing and drinking cans of beer openly. I said that I was hungry. Mark told me it was too early to eat, as if that meant something.

And then we came upon her friend, who I mistook for a beautiful stranger, dragging herself along the path, hysterically weeping. Jean intercepted her, and she promptly fell into Jean’s arms. She was taller, with boyish hair gorgeously ruined by bleaching and framed by elaborate dangling earrings. Mark and I watched her sob into Jean’s shoulder. Jean caressed her ear. This gesture was discomfiting at first, but then I considered that I’d always found contact with my own ears strangely grounding, and after all, we pet the ears of our dogs and cats, so I decided it suggested unexpected assurance and empathy on Jean’s part.

Mark put his hands in the pockets of his navy (fast-fashion) chinos, and I followed suit involuntarily. We were now two men with our hands in our pockets passively watching two women publicly gnash their teeth. If only we’d had an Impressionist on hand. I would’ve felt more self-conscious about the whole scenario, living in the sightline of who knows how many hundreds of strangers and dozens of potential acquaintances, if the two women hadn’t been so well-dressed; as things were, there was a glamorous mystery about our surface.

Ever polite, Mark diverted his attention to a distressingly rowdy football game, but I just watched the show: they were incredibly intimate with one another, and the girl was crying harder now that Jean was coiled around her and cooing into the ear she’d been caressing. I was curious about what was wrong, but I also enjoyed feeling like I’d glimpsed the middle of a sumptuous movie my roommate was watching, that I could stay for a few compelling minutes before going on with the petty day—though, of course, this was, in fact, my real life, such as it was, and I would soon have to deal with social decorum and humane postures if Mark and I didn’t remove ourselves as soon as this started breaking up. Half the bottle of rum survived yet; we could “give these two some space” and heckle puppies at the dog beach.

I waited in vain for Mark, who was older, often took international solo trips, ordered for the table at Szechuan restaurants, and could grow and sculpt facial black hair, to take the lead. I gave him a nod I didn’t know the meaning of; this prompted him to catch Jean’s eye. Minutes passed, and then she pressed her friend’s face further into her shoulder and mouthed something at Mark. We ambled away as she followed, mothering arm around her friend.

My calves were tightening because I’d walked to the park from my apartment and because I, as a rule, abstain from activity. Though the women followed behind, I felt it was still clear to the unaccountably urgent groups passing us that we were a unit. And then the streets were wide once we’d freed ourselves of the park, and the friend’s crying finally reduced itself to sputtering as Mark exhaustively recapped an argument he’d had with a colleague.

Jean announced that she was hungry, and Mark agreed that he was, too, and I added that my legs hurt. I was awarded no response as we waited for Mark and his phone to find a satisfactorily reviewed restaurant. And then in our air-conditioned repose, we ordered a bottle of unnatural wine after the server confessed to Jean that he didn’t have any natural, though he did mutter some clarification about tannins. Jean’s friend was looking at her phone. I watched her text, but after some consideration, I opted not to introduce myself. It felt like the wrong thing. I wanted to do the right thing.

When Jean left for the restroom, I asked her friend (whose expression was emptied from crying) if she lived in Brooklyn. As we made eye contact for the first time, my body responding to it as a call to inchoate action, she said, in some unidentifiable accent, that she’d grown up here. She didn’t elaborate. Mark was texting and hadn’t observed the exchange. I watched them do phone stuff. It wasn’t unpleasant. The friend wore what was left of lipstick presumably smeared on Jean’s dress. Jean was probably in there dabbing at the cotton now.

Wall-length windows, so much light. I was looking into a clean river; I was watching a critically acclaimed movie from the seventies. In it, the server let Jean taste the wine. She was polite about its fallen state. We drank and forgot that we’d met under less cinematic circumstances. The friend hadn’t stopped texting or being on Instagram or whatever for the last few minutes, except when she’d laugh and look out the window and bite half her mouth before resuming. I was starting to sense for her what one of less experience would confuse for a love-like feeling. I imagined the couple of couples on a double date. To the other patrons, that’s how we looked already.

I reached for my drink out of pure habit and somehow tipped the glass onto the floor, where it took its solo and shattered with extravagance. Mark took his face in his hands. I laughed. Jean and her friend laughed at me laughing. Back where he thought I couldn’t see him, our server literally shook his head, but when he arrived at the table he was pronouncing, “It’s fine, it’s fine,” and, “Don’t touch, don’t touch it,” whereas I hadn’t apologized or moved. I guess he was committing to the bit. I raised my sneakers for him to sweep under me. He searched the table for stray shards.

He would bring another glass, he announced.

“Can you get him a sippy cup actually?” Mark said.

Jean laughed. Her friend was placid. Mark was shaking his own head still when the server brought a new glass. The friend was shaking her head at Mark shaking his head, but Mark didn’t see.

“Sippy cup. Sippy. Cup,” I said. “It’s funny hearing a grown man say that. I don’t think I’ve ever heard you say sippy cup before.”

“I mean, why would I?”

“Sippy—cup.”

We were silent except for weird wine-in-throat noises.

“My dad,” Jean’s friend said, “used to get so mad when we spilled. Even water. He got so angry at me for breaking a glass at dinner once, he threw his glass against the wall. Isn’t that funny?”

“That’s fucked up,” Jean said—as I said, “That’s funny.”

“But breaking another glass because you’re mad about the glass breaking, I mean,” the friend continued, as she pointed at me, like, there you go.

Her accent didn’t sound like it was from any particular region, just a little wrong, but it lent the things she said some authority. Anyway I was deeper in love: she’d agreed with me. I knew so little about her. I craved a morning’s quiet conversation in bed, my bed, her bed, when you’re intimate and short until you’re intimate and long, and even your hangover is something nice to share. I resolved at that moment to sleep with her. Though she was far more attractive than anyone I’d ever consider approaching in a bar, the context of my friend dating her friend made it seem achievable—even, as Mark refilled our intact glasses, inevitable.

“My dad got so mad he passed out once,” I said after our toasted glasses finished their lament. “He was, like, clenching his fists and glaring, and this switch in him flipped. And then he woke up on the ground with my mom and me looking down at him.”

I was laughing so hard I could hardly get anything past the second sentence out, and the others couldn’t help but laugh along; to allow me to make so much noise alone would’ve been rude. None of this story was precisely true. I was just floating in the words and the warmth of their attention.

“Thank God, too,” I added—though I’m not sure why I still use that phrase, considering—“because I’d broken this trophy my mother won for a painting in high school. That’s why he was so mad. I was always breaking things. I’d hidden it behind the couch in a panic years before, and honestly had totally forgotten about it. So he was rearranging furniture, found it, and raged his way upstairs. This rerouted my mother’s attention from her disappointment toward the more urgent problem of my father’s anger. My dad wasn’t abusive, to be clear. This isn’t one of those stories. Anyway, when he woke up, he couldn’t remember the last few minutes. I got him a glass of water while my mother snuck downstairs and put the broken pieces in a plastic bag. He was asking where my mother was when she came in with the bag, and he said, ‘Oh, there you are.’ She smiled at us as she threw her golden prize in the garbage disposal.”

“Moms love us so much,” Jean said.

Who knows how long the bullshit would’ve continued if the server hadn’t interrupted us—though mostly he looked at Jean, certainly not me, for I’d disappointed him—to take our food order. This story was partly true. I had once broken my mother’s trophy, but in fact, she was disgusted with me, as if I had told her that her victory, modest as it was, was shit and had defiled the actual memory and not by chance broken a token of accomplishment. I apologized and repented, but she didn’t speak to me for a week. Finally, I slid a little card I’d written under her door. Who knows what it said, but it had the desired effect, maybe because this totem of apology replaced the artifact of accomplishment, or maybe because I was persuasive or sufficiently pathetic. In any case, my father didn’t care. I asked him if what I’d done was horrible—and my next question was, if it wasn’t, then would he please talk to her—but I didn’t get to that question because he stated with his patent flatness and finality that it was between my mother and me.

Anyway, our server, who’d just returned with our elevated fries and elaborate cheeses, had something of the Man in Uniform about him, the handsomeness and authority of a Navy man in generations past—though for this generation, traditional uniforms emblematized the negative qualities of institutions, inextricable from patriarchy if not precisely masculine; basically, it was hard to imagine a young fashionable socialist woman, which is to say a young fashionable woman, getting turned on by a cop or a solider, as these were walking symbols of the thing she and her entire generation had defined themselves against. The only place I’d noticed that lingering Man in Uniform charm was in the outfits of servers and at weddings and at funerals.

Anyway, he brought us plates at intervals, and someone shared facts about climate change while I tried to enjoy the weather. Except for me, everyone at this table seemed to be getting messages in five-minute increments like a lab rat test. I assumed for the girls these were mostly responses to their stories. I’d found Jean on Instagram and then ferreted out her friend by tapping on a picture of the two of them in swimwear on a rooftop. She went by Andi, I learned (and considered whether I should ask her name or just start using it). She had posted a story of the moment I was living. It looked like a nice time.

Mark and Jean were arguing some finer point of climate policy, so I asked Andi about her accent. She explained that she’d lived in Europe, mostly in Paris, from right after college up until six months ago. I clarified that she was, in fact, American, yet talked like this. She confirmed that it was so. I had so much contempt for this idea that it lost all heat; it was so far from what I considered a person could say with a straight face that I was forced to admire her brazenness, while resolving never to trust her with anything serious like mailing a letter or putting her as my emergency contact. Because who knew what someone like that was capable of.

And yet, as she described the clubs she frequented and a boyfriend she’d had out there and a girlfriend she’d had out there, I found that I made peace with this affectation. Everyone has affectations after all. I don’t feel like getting into a masturbatory shame festival at this second, so I’ll spare you, but suffice to say, I have mine. Above all, however, it was not my self-knowledge and aversion to hypocrisy that forced me to accept Andi for what she was, but her beauty, for beauty absolves you of anything.

I took a chance. I killed the last of the second bottle and asked her if she was all right. She asked what I meant. I said I was talking about before. She picked up her phone. She told me it was nothing. I nodded. I wasn’t sure whether this was going well, so I waited. I would never ask a second time. People give what they want to give you. Asking for more is hedonism.

Yet I am not immune to hedonistic fevers, especially when I feel something resembling love.

“I’ve found,” I said confidentially, “that it’s all right not to be all right.”

I didn’t expect her to say more and was hoping for when we were walking later that night or the next time I met her. As I fathomed the empty glasses and the dead bottle and waited for a change of scene, feeling suffocated and bored and wishing the writers room showed a bit more discipline, my phone began to buzz. I assumed it was a long-lost friend, calling to catch up, or dying, but I looked and I knew from the area code (I didn’t have the contact saved) that it was my mother. I stood up and said excuse me like it was the fifties and went to the bathroom to stare at myself in the mirror like it was the seventies and flushed the toilet without using it like it was eighties.

When I returned, Mark was signing the check. He told me how much to Venmo him (a lot). Jean explained that her roommate had picked up a bunch of molly for a party tonight, and they were going to head to her place now to pre-game. I said that sounded lovely. It was unclear whether they were asking me to join, but Mark held the silver SUV’s door open for me, so I got in next to him and Jean. Andi sat up front.

And this is where I met the beautiful and interesting people, with splendid accoutrements not sold in any store, garnishes on each person precise as that of any overpriced cocktail, accents obscuring foundations of beauty and bone structure, and even height somehow, so it was impossible to spot the difference between the impressively presented and the impressive, but there’s more to life anyway, I’ve read, than being impressive. These people wore outfits, not clothes, and refused to believe in accidents. A shirt was not a shirt without a contrasting or complementary pant. Sometimes a bra was a shirt, but they never wore bras when they wore shirts.

So each had insisted his or her or their way into beauty, but a few were born beautiful. Angular noses, gapped teeth, long fingers, aggressive haircuts, bleached buzzes and locks, and technicolor eyeshadow were general. They kept cocaine and ketamine on them like others kept cigarettes and were always bumming my cigarettes. A man in black mesh short-sleeves wore a porny mustache redolent of destiny and a single dangling earring. He kissed me on the cheek, but shook Mark’s hand, and I thought about that.

A diner-style table held the center of the living room and dining room and kitchen; an orange couch was cornered by green fronds. Andi disappeared. I told Jean her house was perfectly decorated, and she admitted that it was her doing. I told her she was an artist. She told me there was a second floor. Music with a singer that sounded like a lot of other singers was playing. Maybe it was one of those singers.

Painted people came and went, and Mark was in the bathroom. I couldn’t tell if anyone knew anyone because no one seemed to notice me. He returned from the bathroom and said Jean had asked us to pick up booze, though I hadn’t seen her do that. And then the open air and lack of crowd refreshed me, yet I was excited to get back in there and attempt to be graceful and interesting. The clothing was so specific, and their hair. I was ashamed that all my clothes did was clothe me and put a nice blur around my person like I had adjusted the depth of field in an image I avoided the center of. They were at the center of the image.

The world darkened as we hustled under blue and purple cathedrals soiled with gold, and our steps rang out on residential streets. I told Mark that I was in fact pretty drunk, and he laughed like it was a compliment to him somehow, maybe because I wouldn’t be drunk if he hadn’t texted me that morning. I reflected on his distaste toward my breaking the glass as I tongued the discomfort and maybe even anger I felt toward him.

And then we bought negroni supplies and many bottles of natural wine as I wondered whether we’d be expected to pay for all of this. He gave the woman his card as I thought about her hair: curly, from the eighties, requiring some product mysterious to straight men. I hadn’t Venmo’d Mark for dinner. I assumed he’d forget. He made a lot more money than I did.

“Andi’s so beautiful,” I said once we were outside. The weather felt less enchanted now, maybe because the sun had fully set. I couldn’t help walking a little ahead of Mark.

“Andi?”

“Jean’s friend.”

“Right.”

I asked him what he knew about her.

“I just met her. I’ve seen her cry though.”

“Yeah, she’s a natural. Maybe we can have a joint wedding.”

“Have you taken molly before?”

“I have.”

“So you’re gonna do it?”

“Planning on it. Are you? Have you?”

“Maybe.”

We stepped around those smoking on the stoop as they smiled winningly at us without adjustment. I almost dropped a bottle on one of their heads, by which I mean I considered letting it slip from my hands to teach some sort of a lesson, but then I remembered that I have nothing to offer this world and certainly not its inhabitants and anyway am rigorously theoretically opposed to violence because I am not strong enough to benefit from it, so I didn’t hurt the stranger who would offer me coke exactly half an hour hence.

Jean and Andi had changed into pale bras without shirts and wide expensive pants. Andi was smoking a cigarette with her whole head out the window (had she been wearing that bra under her shirt, or did she leave it here, or did she borrow one from Jean?), and I saw the bones in her back articulate in high definition. Jean took the bags and started on cocktails. There was this whole throwback domesticity about her, housewife chic, politically permissible because intentional. I admired it. Mark was masculine and at least attempted to stay informed, so it was a nice pairing if, from the unfortunate-pleasure-of-gender-roles perspective, you wanted to have your cake and eat it, too, to use a cliche, to use a cliche.

Jean commenced to drape a lacey tablecloth where Mark and I were sitting. She put out chips and guac. Mark and I watched the headless Andi smoke. Mark asked Jean if he could help with anything, and she told him no. As she put drinks before us, complete with those oversized square ice cubes that she’d melted down with cold water to fit into the rocks glasses, she told us that this cream tablecloth used to be her grandmother’s. I said it was beautiful. She agreed.

Mark touched her wrist as she left the table, and she slipped from it gracefully. The sting rang around the table, and I pitied him for a second. Then I considered that Andi had disappeared again and felt sorry for myself instead. Jean seemed to have taken responsibility for us, and despite the ever-increasing number of people in the house, we were always being hosted at. I suppose this made sense, as she had invited us, and we probably had the least part in the community here, but I felt more waited upon here than I had at the restaurant, possibly because from the server I sensed a condescension laced with contempt (to be served is always to be condescended to!) whereas here the condescension, though no less potent, was sauteed with maternal feeling. More than any almost forgotten orange peel garnish added with urgency to my cocktail, however, I wanted her to simply take my hand and say, “You’re fine. You’re okay.” This would be an odd ask at this point in the night, particularly in front of Mark, and before we’d taken drugs, but I thought that maybe we could work it in later if the mood was right.

Mark and I watched Jean talk to a set of twins with red hair (seemingly dyed?), both of whom I followed on Twitter. They were high up in prestige media circles. I liked being low down in media circles: nothing I said mattered, but I still got to say things. Anyone who wants anything more than that is a sociopath. The desire to influence others is among the most concerning instincts in a human being (!).

The twins sat down. We talked about our jobs. I’ll spare you.

Jean fixed more drinks. She stood next to us and occasionally balanced on one leg and then the other. She was an old friend now because I’d been in three locations with her. I went to the bathroom, threw up as quietly as possible, rubbed the ridges of my teeth with a pasted finger, and used some green mouthwash. (Everything in this house was so curated, except the mouthwash and toothpaste, which were generic brand, I noted.) I sat back at the table, drank three quarters of the cocktail, and hours passed, and the house was crowded, and everyone was beautiful, and Jean and Andi and Mark more so.

Andi, I, and the man with the moustache and mesh shirt were sitting on a green pseudo-Persian rug in Jean’s room as Mark and Jean sat on the bed. The roommate handed us each a clear capsule with splintered litter in it called drugs. We washed it down with our cocktails, except for Jean, who, though she was making all the cocktails, was drinking a glass of gin on ice. An abstract chemical taste took over my mouth and throat, but maybe that was just sensation manufactured by attention to my body. The guy whose head I’d considered dropping Campari on entered and was welcomed by everyone but Mark and me shouting his name, though he said nothing and just gave a little wave before he kissed the man in the moustache and mesh shirt and started breaking up coke on one of those cheap artbooks of Hieronymus Bosch they have halfway up the stairs at The Strand.

Mark was looking at all the objects in the room. He passed on the coke when it came to him. I didn’t pass on it. The man who’d been kissed handed a capsule to the man with the coke before announcing his Venmo, causing everyone to take out their phones. I just checked my Instagram, hoping he wouldn’t be careful in his accounting. I saw the little red scar over the green phone icon indicating a missed call from my mother and put my phone away, though this wasn’t a long enough time for me to have completed the transaction, because no one was paying attention to me anyway.

And then finally I was sitting next to Andi at the table, as we talked quietly to each other, as the drugs gave me a feeling of mild fever. Our speeches were quick and quiet. You could never be sure what was placebo in the early stages because the truth was when you were high enough you’d deny that any symptoms were the product of drugs and just say, no, this how I talk, or but listen to me for a second; by you, I mean me; obviously; always.

I asked Andi what she’d been doing in Europe, and she told me in that insane accent as she raked her hands across her pants, and I snuck unsubtle peeks at her exposed body, that she was a musician and had been living as a singer-songwriter, kind of touring but mostly playing any shows she could. That was cool, I said. She said that she was getting some plays on streaming services, and that now random people would follow her on Instagram, and even DM her and tell her that her song meant something to them. I said that was cool.

I asked her what she’d been upset about earlier, and she looked at me flatly, and it hurt me. She asked me how long I’d lived in New York. I said I’d gone to NYU, so since I was 18, so nearly a decade now, which was not where I’d gone to college and not how old I was. I found that if I broke character early, it freed me up to be more authentically myself in other ways because I didn’t have to worry about these things coming back to haunt me, because who was that matrix of half accurate data anyway. I asked her if she had any gum. She asked me if I had any gum. I told her I’d find us gum. To me, this was chivalry.

At some point, once Andi was elsewhere, I spilled my drink all over the table and knew that the red of the Campari was bleeding into Jean’s grandmother’s tablecloth forever. I considered that I could find Jean but told myself that the damage was done. The party itself had done it, really, the fact of the party’s existence, not me. I didn’t react because I didn’t want to draw attention, and I didn’t check to see if anyone had seen.

And then outside on the porch smoking cigarettes and giving away nearly the entire pack to the piranhas immediately upon taking it out, I met a large bearded man in short shorts yawping authoritatively to no one in particular. Because I thought he’d be an easy audience and because I can’t help but support someone who’s bombing, I engaged him and found out that he’d worked with Mark before my time at the company Mark and I had met at years ago. We talked for so long that a whole other group of smokers came out and took the rest of my pack.

Finally, I asked him if he was on molly, too, and he said, “Oh yeah,” with gusto.

As we talked, it occured to me that I should wonder about Mark and Jean and Andi but couldn’t bring myself to actually wonder, and anyway I asked him what the furthest he’d gone with a guy was. He explained that he’d once blown a friend of his from college. I asked him how it went. He said it was pretty good. They’d come home from the bar together; it had just happened. A few minutes later, he asked if I wanted to make out, and I looked at him and told him not right now. He nodded in that on-drugs way like I’d said I’d prefer to wait another hour for dinner.

And then we were discussing the physical fact of penetration, and I was saying I didn’t feel like I’d prepared myself psychologically for it. He was having a whole other conversation paralel to mine and billowing silver plumes the beauty of which would distract me from time to time, so I had no idea whether he agreed with me or not. At some point, he said that, in fact, he had experienced penetration, and often, just not with a man.

I forgot to mention his clothes were bad. Anyway, when he was with the woman he’d now been dating for three years, he would at times wear a dress and she would fuck him in the ass with a strap on. I nodded and said right, right, right.

“You’d be surprised, man,” he said. He looked back and forth like he was taking me into some financial confidence. “Women see a man in a dress. A beard like mine. Something happens.”

“Right, right, right,” I said.

And then Andi was out on the stairs with us. She leaned on the railing next to me, and I was grateful. She asked if I’d found any gum. I asked my new friend. He handed us mint green sticks wrapped in white paper with which I struggled. And then he thought about it and handed us another. To me, this was chivalry. She asked me if I had another cigarette. I said yes but then looked and didn’t have one. I didn’t say anything and just let her deduce the sad fact. If I would’ve responded, I would’ve apologized and apologized and debased myself.

He handed us both cigarettes and lit them for us. It was just the three of us. “A beard is a dress for your face,” I said. He laughed and laughed and laughed. He was on drugs. I was on drugs.

Andi was on drugs and smoked and looked at the building across the street. She said that she was so high. I asked her what she was upset about earlier. She caressed the railing’s decorative flourishes. She said that she was upset because she’d been thinking about something horrible and unmentionable that had happened to her a long time ago because she’d seen the agent of that badness on someone’s Instagram story, and sometimes when something is unexpected like that, it fucks you up harder than you’d ever expect. I was sorry I’d asked. I was sorry I’d asked a second time. I was sorry I’d asked a third time. Anyway, I didn’t know what to say.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” the bearded guy said.

She nodded like thanks, like it was nice to hear even if it couldn’t change anything. And I saw myself through the haze of the drugs or reflected in the haze of the drugs like fire in smoke, saw the empty thing at my center, the chamber in which the things these people said reverberated and which made them sound just slightly off. In my horror at who I was fundamentally, I couldn’t even bring myself to say, “Yeah,” but it didn’t matter anyway, because Andi and the guy were experiencing community with one another facilitated by MDMA. I tried to stay focused on the badness within me, but the drugs were distracting me from the woe at hand, and instead I just felt glad for their community and thought that it was nice that in this moment and in this world they had each other.

And then we went inside, and there they all, spectacularly, were, her close and beautiful friends, my new friends, perhaps. They spoke to me, and there was nothing wrong with what they were saying; they were attentive with their eyes and often held or patted or squeezed my shoulders or leg or hand. I had the sense, however, that I was the child of a friend being humored with a comfortable condescension. I admit that I felt safe.

I should also mention that eventually I wandered up to the second floor and into a dim bedroom lit by a single lamp shaped like a cat where a few people and I, including one of the twins, and the bearded guy, phones dark in our pockets and purses, watched Andi in long shining beautiful black leather gloves spank the other twin with a fake sword as she was called daddy.

And downstairs again I ran into Mark. Leaving Jean’s room, he was shirtless, visiting the bathroom post-coitus, one assumes, possibly covered in sweat or maybe a slight visual hallucination was marring his edges. Music and laughter seeped through the ceiling as I experienced motion sickness from speeding across time. I’d been caught in the act of considering the tablecloth I had ruined, revisiting the bloody scene of the crime like a rookie, before I escaped into the generous night. The kitchen was so dark, however, that he likely couldn’t even see a cloth on the table, let alone the stain. He asks me what’s up, and then he asks me what’s wrong, and so I say nothing.