Her mother never showed for meets, so Helen was surprised when she heard her voice. During the relay. Cheering loudly from the stands. Helen planned to take the bus with her team afterward, but once she’d showered and dressed and checked her split times, she found her mother waiting in the parking lot. June had no jacket on, and she was pacing back and forth along the side of her Volvo. When she looked up and saw Helen, she uncrossed her arms to wave with both hands.

Huh, said Anna Chen. I’ll tell Coach you got a ride.

They weren’t friends anymore, not since ninth grade, but she knew enough about Helen’s mom to be surprised to see her. Embarrassed too, from the look on her face.

Helen hurried to the car and got in.

Hey you, her mother said.

The engine was running, and June held her hands to the vents.

Hi, Helen said, and put her seatbelt on.

She watched her mother put the car in reverse. Watched her pull out of the parking space, out onto the road, and watched her put the blinker on to turn left, slowing for a yellow as the traffic light approached. Helen slid her swim bag to the floor and unzipped her coat. Her eyes never left June. She was watching for tells.

If she was talking, it was her slack sort of smile, the way her mouth labored extra on each word. When she cooked, it was the slide of her knife, too slow through an onion she had already minced. In the car, it was the way her mother’s hands stroked the wheel. Back and forth across the top, a pair of wipers set as low as they can go.

But today June wasn’t doing that. She turned onto the Parkway, hands gripped at ten and two, and then accelerated appropriately into traffic. Across the median, a long trail of rush-hour commuters crawled homeward from the city.

I thought butterfly was your stroke, said June, still coasting in the right-hand lane.

I’m not tall enough anymore. I like free just as much.

Well. You’re just as good at it.

Thanks, said Helen, though given how little June saw her swim, it meant nothing.

She watched the guardrail blur by, and squinted at the curtain of drab trees just beyond. Every valley shall be lifted up, she thought. Every mountain and hill laid low. She didn’t mean to think it, and she didn’t want to. It had just been in her head since chapel yesterday, and it was starting to feel like a game of tetherball. The verse swung by, she batted it away, then it came right back around again. Every mountain and hill laid low.

Usually, she didn’t listen to what Father Gallo said. She let her eyes wander the room while he spoke, and she had been staring at the ornate cornice piece along the Chapel ceiling when he read out the Gospel yesterday. Every valley, he said. Every mountain and hill. She missed the context when he gave it, and the words seemed hard to square with the gold-leaf plumes in her view, the carved wood swirls that capped the walls.

You tired? asked June.

She reached for Helen’s forearm and stroked it, a quick back and forth.

I’m okay.

And homework? Is there lots?

She was using her cheerful voice. A taut guitar string, pitched too high.

I guess the usual, said Helen.

June was back to counting days; she’d been sober now three weeks.

There was actually another time, just one, when Father Gallo had said something that stayed with her. It was about a monastery off the coast of Croatia, or maybe in the Mediterranean. She couldn’t recall the story exactly, just the journey required to get there. How the abbey was on an island in the middle of a lake, which itself was on an island in the middle of the sea. The image had appealed to her, like the thought of a bed piled with blankets she could disappear beneath.

I was thinking taco salads, said June. For dinner.

A smirk escaped before Helen stopped it. Taco salads weren’t microwave food.

Wow, she said. Ambitious.

June smiled, but with effort, to shrug off the slight. Then she said, Piece of cake! We’ll just swing by the store.

Before they left for college, it was Helen’s brothers who picked her up from practices, or meets, or whatever she had going after school. Back then June cooked most nights, and they would come home to soup on the stove, spaghetti and garlic bread, a chicken roasting in the oven. But Helen was so used to calling for pizza now or filling up on cereal, it hadn’t even crossed her mind that dinner might become a thing again.

Traffic was getting heavy, June kept having to brake. Beyond the guardrail was a hillside now, dense with trees, that rose right up from the road. They were near a county park, or Helen thought so, where her class came in grade school for field trips. Her teachers had once staged a dig there, planted relics for the kids, and Helen still remembered the arrowhead she found. She had traced its chiseled point along her palm, then clutched it in her pocket on the bus back to school. I can’t lose this, she thought. It was lost for so long.

June’s cell phone rang, in one of the cup holders between their seats. They could both see it was Jody calling, and right away June veered the Volvo toward the shoulder.

Just call her back, Helen said. Like once we’re home.

It won’t take long, June said. I swear.

At this, Helen wanted to laugh. Or to grab the phone and pitch it to the back of the car. The last three weeks had been Jody non-stop, hours of phone calls, June’s closed bedroom door.

Sorry Hellie, said her mother. Not a long one, just to check in really quick.

June threw the car into park, and just then the ringing stopped. She unbuckled her seatbelt and dialed Jody right back — Hi there, Hi, yeah, I’m sorry. She raised a finger, just one minute, and opened her door to get out.

You can’t be serious, said Helen.

Her mother hurried to the front of the car, past the hood, and stood right at the center of the windshield’s scope with the phone up to her ear. A big-rig truck sped by, a rush of wind that whipped June’s scarf into her face and blew her hair around.

She paced away from the car, and then back, looking down at the ground, shoulders hunched at the cold. Where’s her jacket? wondered Helen. Then she thought, I should be on the bus. I should have just taken the bus.

This wasn’t the first time her mother had tried AA, and Jody was not her first sponsor. The guy she had last time was fine, but he always insisted on meeting June in person. And she had been willing, drinking coffee for ages in some diner booth with him, while Helen took her bike to the store so they’d have something in the fridge. She hadn’t noticed at the time, back when it happened, that her mother stopped going out to see him. Then one afternoon, arriving home from study group, Helen found the whole second floor of the house flooded. June had passed out—in her bed luckily, and not the tub—while running a bath in the middle of the day.

Looking back, it almost seemed funny. Now that she knew things could get so much worse. Her mind instantly flashed there, to the dim light and the sirens and the panic and the cold, and she had to blink her eyes hard to make it all stop. Every valley shall be lifted, every mountain laid low. She reached for her bag. Then she remembered that her cell phone had died at the meet.

Her mother stood still now, waving a hand around, as if speaking to the traffic. Helen tried to imagine the words or the story that might go with that, but she had so little sense these days of how June spent her time. And then, for the first time maybe ever, it dawned on her. How nuts it was for her mother to be so private about getting sober when she had been so public about getting drunk. The thought made the back of her neck hot, and her face. She had the urge to jump into the driver’s side and rev the engine, shout get over yourself through the window, or to honk the horn and just keep honking. Instead, Helen opened her door and got out.

June snapped her head up and asked, with just her eyebrows, what she wanted. Making a show of it, Helen zipped her coat and put her hood up, like a normal person this time of year. She leaned against the car door, clear she intended to listen. This made her mother go quiet, then made her turn away and walk farther on.

If Helen was annoyed when she stepped outside, she felt massively irritated now.

She looked down the road, toward her mother’s turned head. She looked at the trees, the damp hillside just a few yards from the car. She looked back at her mother, who had yet to turn around, then she swiftly stepped over the guardrail.

She crossed the grass strip, and when she got the hill, started climbing. She climbed in long strides, keeping steady with her hands, on all the rocks. She moved quickly, never looking behind her, and soon she had the sense that all the Parkway sounds floated up to her now, instead of surging by her from behind.

Helen, her mother called out. Helen, wait!

But by then she had climbed the whole hill. She picked her way through some shrubs at the top and kept walking, right into the woods.

◆

June didn’t quite believe what she had seen. She glanced into the car as if her daughter might be there, as if she might have only imagined it. Then she leapt over the rail and ran to the hill, ready to follow. But Jody’s voice was still there, small but shouting, through the phone June forgot she was holding. She hung up and started climbing.

The hillside was damp with melted snow. June’s clogs were too big, they kept coming off her feet, and since she’d left her coat at home she was shaking with cold. She couldn’t go farther, let alone scale the slope. She called Helen’s name again, a few times, then made her way back to the asphalt to see if she could see her from the road. Helen, come on! But the hill looked just as it had when she pulled over next to it — wild and ignored, as if no one had set foot there for years.

She got back in the car and called her daughter’s phone. Right to voicemail. She called again, then hung up without leaving a message.

On Saturdays when the children were small, June used to drop them at a neighborhood piano teacher’s house. Only the boys took lessons, but the teacher didn’t mind if their little sister stayed in the other room, so long as she was quiet. A single mother, June had relished that free hour. She would leave Helen with a bag of cheese curls and a picture book, then run an errand or finish up the laundry in the quiet of her house. When she returned for the children, every time—and this is the image that now came to her in the car—Helen would be waiting, fingers caked in orange dust, just exactly where June left her.

Her sons had required so much more of her. Born barely a year apart, they made her feel like she was facing a team. Like a manager and assistant manager, always on duty.

Even once things started slipping, she would pull it together for their baseball tournaments and science fairs, and later, for their college tours. But for Helen, three years younger, there had been less of that. Or if June was being really honest, none.

The story she told Helen at first had been migraines. That covered things for a while. But then there came the morning when Helen had already left for school by the time she got herself downstairs. To the kitchen. Where a pyramid of her empty beer cans had been carefully constructed in the middle of the floor.

Beer wasn’t even what she drank. She used to have one in the morning sometimes, to lift her mood. But she didn’t like recycling the cans with Helen’s sodas and things, so she stashed them all under the sink, where her daughter evidently had found them. She remembered rushing to the floor, breathless with shame, and how she’d scooped the cans into a trash bag, along with the few beers that were still left in the case. She went to the garage to throw them out, then returned to the kitchen and poured herself a glass of gin.

But this was exactly what Jody kept talking about, what she always told June not to do. Your mind is a dangerous neighborhood, she said. Don’t go in there by yourself. And it was true; her mind was a grim tour to go on these days, a string of disgraces, linked one to the next like those scarves that keep pulling and pulling from inside a magic hat.

June put her seatbelt on — she needed to move. If she drove to the next exit and got off, she could loop around this stretch of the Parkway again, just in case Helen came down. She pictured her daughter walking along the side of the road. Pictured her with her thumb outstretched, pale chlorine hair, trying to get a ride back home. She imagined pulling up to her, how she might bend to the window and wave, the way she had years ago, when June trailed her in the car, selling cookies door to door. Then she saw Helen’s face, just last month, leaning over her, crying, on the front walk that day—Don’t go in there by yourself—and June clutched the wheel, shook her head, and stayed parked.

The police, she thought then. She should call the police. But then what would she tell them? My daughter escaped from the car, officer. No, I don’t know why. No, her phone is turned off. I think she just needed out, she just had to get away. From me.

June reached for the dial on the radio.

Murray, her first sponsor, had always played oldies in the car. You must want to hear me sing, she’d once said, to make him laugh. But Murray, she remembered, had been charmed by whatever she said. It happened so quickly, how they had gone from meeting for coffee, to having long meals at the diner, to then meeting at the Comfort Inn in Edgewater. And it was always motels with them, because Murray had a wife at home. And June, of course, had Helen.

She knew it had been foolish to pick a man for her sponsor, and she knew that at the meetings she was judged for it. But the truth was, Murray helped her. Five months he kept her sober, the longest stretch of her whole adult life. Then one afternoon, while he was buttoning his shirt and she was brushing her teeth at the motel sink, he’d gone and said the exact wrong thing.

I’m going to leave her, he said. Since you’re doing so well now.

He was looking at her, smiling in the mirror, and June froze. She blinked at his half-dressed reflection. Then she made herself smile back, and said, Tell me in a minute. When I don’t have toothpaste in my mouth.

He laughed, predictably, kissed her on the cheek, went and sat on the bed to wait. June closed the door and locked it. Then she looked through her travel case for the bottle of mouthwash she always had with her—the only place she kept booze—and as soon as she found it, she took it down in one long drink. Murray had waited only a few minutes before he started knocking, and when she wouldn’t answer, pounding. He refused to go away, pleading with her to come out, until she said quietly through the door, I’ll come out once you’re gone.

Please, she had said. You need to go.

June kept the radio on Classical now. She liked not knowing any of the music, how the pieces brought nothing to mind for her, no triggers that might start her down a spiral. And when the announcers came on to say what they’d played, June would find herself repeating them. Dvorak, she’d say. Beautiful. Haydn. I had no idea.

The phone rang again. Jody. Again.

It was starting to get dark, and the thought of Helen in the woods made her chest tight. She meant to answer Jody’s call, but her breath was speeding up, panic swimming through her brain, which after everything, felt somehow absurd. As if it were even a role that she played anymore, keeping her daughter safe.

The thing to do, June decided, was loop back around. Get off the Parkway as soon as she could, backtrack this stretch, turn the car around, and go Southbound again. She’d take the next exit, she knew that little town—pizza place, laundromat, liquor store—and she would just pass straight through. She really would. Then look for a road sign, to lead her back the other way.

◆

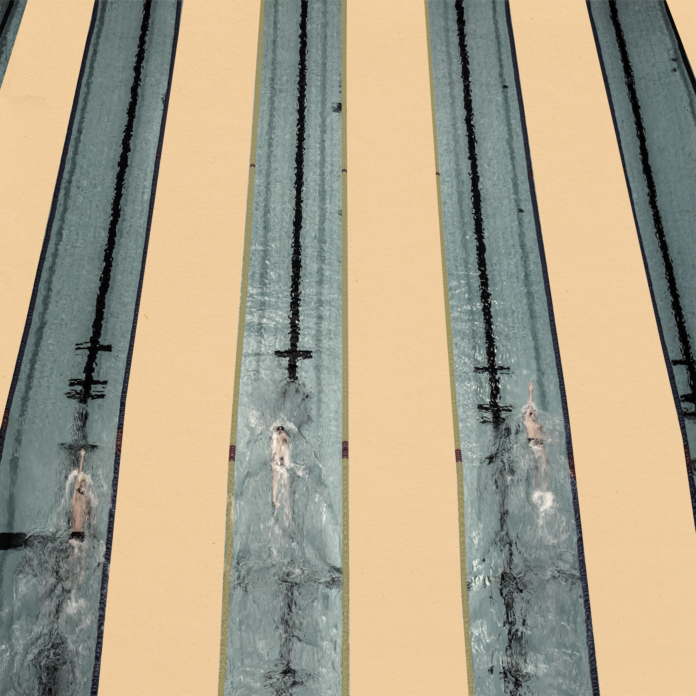

Helen had been walking a long time before the crocuses cropped up. She had her head down, moving fast, then all of a sudden they were everywhere, freckling the floor of the woods purple. She had to be careful not to crush them, slowing her pace some, but she didn’t mind. It had been a long time since she walked through any trees. They must absorb sound, she thought. Being inside them felt like being underwater, in the pool. That same humming feel of a buffer, like if noise was around it couldn’t reach her.

Her feet were so cold she hardly felt them; there was no clear path, so she’d been stepping through snow. This was all county park, she assumed, a trail would have to appear at some point. Or maybe she would end up in one of the parking lots? She imagined her mother there, knowing by some miracle where she should wait. She pictured her back on the roadside, still on with Jody. Then saw her pacing at home, or on a barstool someplace. Then finally, she pictured her here. In the trees. Not far behind, on the carpet of crocuses.

Her anger felt less like a brush fire now, and more like some coals staying hot. She had wanted to keep walking forever at first, but now she just wanted to stand still. She stopped in a cluster of pines, very tall, dizzying to look at, her head tilted up. Breeze swayed the top branches, but it wasn’t a wind she could feel from down here.

Helen placed her hand on the trunk of the closest tree. Its bark was rough, and flaky. A piece got chipped away under her thumb, and she pressed her finger to the little red patch exposed, the silky wood. She chipped another piece from under her middle finger, and then her index finger, and then she thought—she could have sworn—that a kind of charge ran up into her hand. She felt some warmth, at least she thought so, from the few tiny spots of bare tree.

When Anna Chen used to come over, back before the bathtub flood, they liked to sneak out on the roof, the not-steep part through her bedroom window. They were too scared to stand, so they would scoot around sitting, palms flat against the asphalt shingles. Helen remembered how good and warm the shingles felt, surprisingly, the way the skin of the tree felt now. She rested her forehead against the old trunk. Closed her eyes.

Helen wished she were back at the meet. She wished she were up on the starting block, before her race, straining toward the cool slap of water that meant she actually knew what she was supposed to do next. She should have worn a hat today, some gloves, or at least charged her phone in the locker room. Overhead she heard a bird call, then another one wailed, calling back. At the shrill note, she snapped her head up.

She looked back through the trees. Listening with every muscle she had.

The morning it happened, there had been a lot of snow overnight. The biggest snowfall of the year, people said. Helen still planned to walk to morning practice, she was hurrying out the door, but when she stepped outside, she stopped. It took her a second to know what she was seeing, but there, under the deep white on the front walk, was June. Helen rushed to her mother, knelt beside her, and lifted her stiff head and shoulders to her lap, shouting Please Mom, oh please to revive her.

Sometime in the night, June had locked herself out of the house. She had blacked out in the snow, where she still was come morning, hypothermic, barely breathing, and blue. Helen had called the police, though she didn’t remember doing it, and by the time she heard the wail of their sirens, she was sure that her mother was gone.

She took off running now, fast through the trees, high stepping over limbs on the ground and following her footprints in the snow. She didn’t avoid the blossoms this time; she didn’t, in her fear, even see them. She knew better than this—just go easy, don’t trigger, all costs—and what had even been the point of it anyway? It was almost dark now, and when she reached the crest of the hillside she’d climbed, all she saw were dots of light, the string of cars down below. No emergency in sight.

Still, she raced to the road. Long strides, head down, she flew down the slope like she was crossing the pool, not pausing for air until she hit the asphalt, on the shoulder, where she had last seen June. Every valley shall be lifted, every mountain laid low. She clasped her arms over her head. Breathed, as traffic glided blindly by her. Helen knew there was nothing left to do. Just to walk to an exit, somehow get herself home, and find whatever waited for her there.

She hadn’t walked far when she heard a set of tires turning gently off the road, and headlights brightened everything around her from behind. She turned around, and there it was. The Volvo. Just the sight of June’s outline, her shape at the wheel, and Helen suddenly felt eight years old again. It was so long since she’d thought of this, but that was the age, the year, she had asked her mother to drive alongside her, selling Girl Scout cookies in the neighborhood. Her troop, she remembered, had been trying to beat some record. She didn’t once need her, it kept slipping her mind to even wave between houses, but then she got really cold and ran back to the car. June had passed her a thermos of sweet, steaming tea.

Maybe this will help, she’d said. If you don’t feel like giving up just yet.

Now, on the Parkway, June stopped the car with a few yards to go. Helen at first just stood still. She stayed put, squinting in the light, as if choosing. As if she had any choice. Then she walked toward the car and bent down to look in. June leaned sideways in her seat. She rolled down the window, and smiled.

Fancy meeting you here, she said.

Helen slid into the passenger seat. An orchestra played soft on the radio. She watched her mother pull onto the Parkway again, watched her check the mirrors before changing lanes. She picked her bag up from the floor, and felt in her lap the familiar weight of her swimsuit and towel inside. All balled up together, soggy as spring.