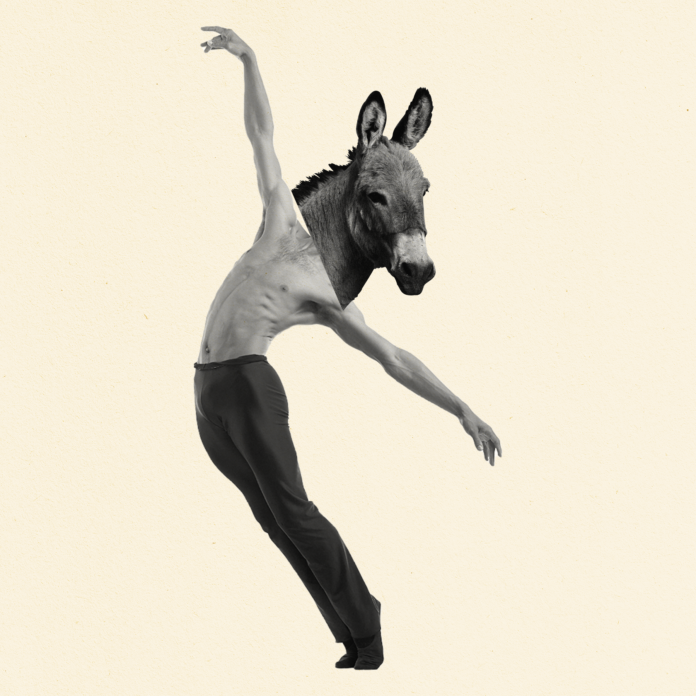

He would be a horse’s ass. He had been auditioning for ballet companies and responding to calls for small parts for a year when he got the email: Adam would be one of two men manning the horse, his legs in white tights descending from the rump of the giant horse in Don Quixote. They needed someone of the right height.

Patty had never really thought about how when you were casting a donkey or a horse you needed to have two sets of matching legs. The guy at the front had to have puppeteering skills, needed to have that somewhere on their resume, she supposed– she hadn’t realized until she met Adam that dancers even had resumes. The one at the front also steered. To be in the back was to know the marking and to blindly trust someone with limited visibility: the massive head was small-eyed.

After the first night of rehearsal, Adam told Patty that the Jerard, the other half of the horse’s ass, was quite a bit older. You couldn’t tell by his legs, of course. Patty was learning that older in dancer code could mean anything when it came down to men: there was a shortage. If you had the skills to get through certain ballets, there would always be work. Jerard, it turned out, did not have the skills. He was known to be reliable. He was a moderate height. He was relegated to party scenes and animals. Adam assured her he was nothing like Jerard.

“You have to start somewhere!” Patty agreed. “Also, hello! A pandemic!”

The conversation about Jerard had depressed her. Being nothing but reliable was the worst conceivable fate: she should know. She was the daughter of doctors, an OBGYN and a heart surgeon, which meant, if her peers at Berkeley High were any indication, she had to either become a brain surgeon or an installation artist. Being neither, she blamed all of the afterschool and summer activities that had eluded her when she was sick and missed most of her junior and senior year. Now she never called in sick.

Adam had performed the lead for every ballet at his performing arts high school in Western Mass, and then again at Oberlin. He could have immediately made it into the corps of a regional company in the Midwest, he told Patty on one of those first dates when they stayed up all night walking the city. But why be a big fish in a little pond? Why settle when there was– and he had gestured at the night sky of skyscrapers. He knew what he wanted. Patty admired that.

Patty didn’t ask how much the new gig paid. She was used to covering their rent, which was doable because her parents helped out, and because their one bedroom was really a studio with an alcove for a bed and a shared bath on a hall, that, luckily, housed solely one other studio, inhabited by a woman Patty knew from work. Adam had moved in after a month of pandemic dating: why pay two rents when they were one another’s pod, never apart? She honestly couldn’t understand how dancers made a living, though it seemed that most of them were on unemployment, or at least went on it between seasons if they were lucky enough to be with a company.

Patty had never imagined she would date a ballet dancer. She didn’t think this was due to some kind of sexism on her part, it was just the odds of things: how many were there? The men she’d dated had always had steady jobs, and when Adam popped up on the app two weeks into pandemic, when she was lonely and only seeing friends for long walks through the city, she’d said yes because he was handsome and loved silent movies and penguins, which, they had agreed on their third date, at the Central Park zoo, was an understandable pairing, best celebrated by a Black and White cookie. Adam turned out to be funny, silly even, and charming and affectionate, and they had a peaceful pandemic nesting period before life picked up again. Those were the days when no one Patty knew had work.

When she had gone back to work, he hadn’t, until landing this part. She was proud of him, she was. It took guts to stick to a dream, to even have one. She wasn’t sure if this really was a stepping stone. She had only seen his legs moving across the stage, and each time she stood up at the end of the performance so she could see him in the back row for the final applause and try to generate a standing ovation, which only happened once, she was reminded that she still hadn’t seen him actually dance. So that’s what it’s like to love, her hallmate Nan joked: you cheer a horse’s ass.

The truth was, she barely looked at Adam–well, his legs– on stage: she was distracted by the somewhat realistic, but also very absurd, horse’s head. Wasn’t it amazing how far puppetry had come? Or maybe it had always been there: she realized she knew nothing about puppets, or automata, a word she only vaguely knew until she followed her curiosity about animals onstage online and then wandered on to sites solely about automata. She liked the animals–the humans were too creepy- and she watched and rewatched videos of mechanical swans and mice and birds– so many birds. She stumbled across a kit for a hardwood and plywood automaton horse online and ordered it for just under sixty dollars, plus sandpaper and glue she got at the dollar store: it would make a perfect gift for closing night. She needed a project. The horse was 6 x 6 x12: how hard could it be to put together?

Every morning Adam was at the barre- otherwise known as the less wobbly chair in the kitchen corner of the studio- when she woke up, and then he was out the door for rehearsals, a performance, then home late each night. Patty had more time to think about the future now that she sat alone in the evenings and on weekends, drinking green tea, puzzling over the automaton kit, watching videos, and feeling like the city was moving around her and without her. She was stuck at her tiny kitchen table, still afraid to go out into the increasingly unmasked world after work. In high school, her bedroom had been a protective bubble for her lowered immune system, her only connections to anyone besides her parents was through LiveJournal. She missed LiveJournal, really missed it: Instagram just made her feel more outside of everything.

“What’s new?” her mother always asked her on their weekly phone call, the edge of hope bubbling up in the question, and fading in her tone when Patty talked about the weather, or the children she taught at work. “Tell me something new.”

Patty thought about applying for a PhD in biology, but what was the point of getting a job in a lab if you weren’t someone with original vision? To be the legs on someone else’s horse, with no course of your own? She had always thought she would do something with vision, like her parents expected, and now she was thirty, or would be in a few months, and her parents were coming to town. They were going to meet Adam, and for this initial introduction, they would see a horse’s ass. Patty wanted to think that they could be open to the idea that an artist’s life could be worthwhile. They were both doctors! They had season tickets to the San Francisco Ballet!

Her mother had been thrilled when Patty told her about Adam.

“None of us are getting any younger,” she said.

Her mother was a gynecologist who threw around the term geriatric pregnancy, and she had not held back her concern about Patty’s thirtieth birthday, even though age didn’t matter if you no longer had a uterus. Patty did not tell her she had not told Adam. Wasn’t that the benefit of moving 3000 miles? No one knew what everyone else at home knew about you and the inside of your body.

The directions for the automaton horse said “expert level,” but Patty wasn’t concerned. She was a scientist. Or at least she had been a biology major, so she had once been someone who thought of herself as a scientist. Now she wasn’t sure. She worked at the Natural History Museum as a physical science educator, which was science adjacent.

She read more about automata on her lunch breaks, and she began to grow interested in the imitations of humans, too. Her favorite story was that of the giant chess-playing automaton that fooled people all around the world.

There was a tall man hunched inside the cabinet below the automaton.

When she tried to tell Adam the story, he laughed and said, “God, people are dumb,” and asked her to massage his legs. He fell asleep face down on the bed.

She missed those early days when they had nothing but time to talk. They talked about everything–movies, books, his childhood, their hometowns, tv shows, animals–or almost everything. It was simple, really, her omission: Patty had cancer in high school. It wasn’t a big deal, she would say when she told people in college. Radiation and the removal of her uterus. Everyone liked to respond with a canned positivity: you will adopt someday. It will be so great. You will adopt all the children, all of them! That was the joke that all of her high school friends, and then all of her college friends, liked to make, emphasizing all. As if it was so easy, as if she was Mother Ginger in the Nutcracker and she would gather all the children under her skirt and live happily ever after.

Mother Ginger was always played by a man.

It was better not to tell anyone the truth, especially if you were dating them. Because what she did know was that even college boys who didn’t want to get anyone pregnant were freaked out by a girl who didn’t have a uterus.

Two nights before closing night, and the arrival of her parents, Patty still had not completed the automaton. Everything needed to be aligned perfectly. She kept dropping parts that rolled under the stove and sink. In the online comments, she saw that grade school children had made it with ease, but adults seemed to need power tools.

She couldn’t even make a damn wooden horse from a kit made for children.

Who could plan to bring a child into the world anyway? The headlines were full of guns and war. In the years since college, she had learned how much adoption cost, and had then read all about foster care: reunification. Reunification. What did it mean to raise a child and have them be taken away? She stopped scrolling through the Waiting Children websites. She couldn’t bare the narratives of loss, of risking exposing a child to the risk of more loss. If she were a bigger person, yes all of the children would be swept up under her skirt, and she would build them horses and she would teach them how the horses moved, and she would teach them the realities of the body, what it meant to have a real quadricep, chiseled and strong.

She learned from Adam that Mother Ginger was usually played by the tallest man in the company. If he were a little taller, he told her when scrolling through calls for male dancers, he could get hired in by some regional New England companies every Christmas. She googled “men ” and “Mother Ginger” and learned the children under Mother Ginger’s skirts weren’t called children but polichinelle. She googled polichinelle and discovered puppets whose origins were a bawdy little figure born out of an egg. The world was full of puppets and automata created by men. How else could you make a life when you couldn’t give birth?

Patty continued to massage Adam’s legs every night when he came home from rehearsal. It wasn’t easy to be a horse’s movement. A dancer was first and foremost a body, she understood that now. How could she tell him about hers?

Patty had watched Adam train every day through the pandemic, going through the motions of the ballet barre in a tiny space and leaping across Central Park. He hadn’t given up, he hadn’t questioned his path. Patty had been on unemployment then, furloughed by the museum. For a while they put her on special projects and then they were sorry, they were so very sorry. That was the lesson of the pandemic: nothing was for-sure. You reached for the lowest rung, the simplest job, the steadiest job with benefits, and that too could disappear. What else could she do? How could Adam be so sure of his path?

One afternoon when they were spread out on a blanket in Central Park, she asked him.

“It’s funny,” he said. “I wonder if people ask basketball players that question?”

“Fair point,” she said. But was it? Didn’t athletes get questioned all the time about how they got where they were?

“What else would you do? Besides dance?” she asked.

“People with a Plan B aren’t committed to Plan A,” Adam said. “I mean, I think the job of any artist is to believe in yourself. No one else will.”

It seemed to Patty that paying someone’s rent was a form of believing.

“Not you,” he qualified, as if she’d spoken aloud. “I mean– you have to be confident.”

“What about, later,” Patty asked. “I mean, after ballet?”

“After ballet?” he said. “What’s gotten into you? Are you thinking about grad school again?”

Did Adam even want children? It was impossible to ask him without having to tell him the truth, and somehow, he had never said anything about it for three years, but that was typical of guys, wasn’t it? She found herself going back to the Wednesday’s Child videos: news channels highlighted an “available” child every week. How humiliating, she thought: it was just like the segments on dogs on other news shows. Those video clips would live on forever and the children would find their lost child selves forced in front of the camera. And why was making a life such a big deal if all through nature, including humans, biological parents disappeared?

There was no way she could stop her parents from bringing up the cancer, and probably grandchildren, in front of Adam. They were always saying that they wanted to be grandparents. And soon! “We’re not getting any younger,” her mother had texted her along with a photo of a cousin’s newest granddaughter.

“Love makes a family,” her mother would always add when she brought up children, as if she hadn’t said it before, as if she thought that somehow Patty would feel like she was demanding some sort of impossible biological imperative.

On the morning of closing night, and her parents’ arrival, Patty woke up sweating, although the windows were open, the air cool. Her parents would check in to a hotel in Midtown, and soon they would all be sitting in the audience waiting for the second act when the horse would make its entrance.

Adam was already in the kitchen, dropping spinach into the Vitamix.

“Hey baby,” he said.

“Baby, hey,” she said back. It was their schtick.

Speaking of babies– they never spoke of babies. All she’d had to do was say she was on the pill, and he hadn’t seemed to notice he never saw any pill packs.

“Adam,” she said, but he was at the door, thermos in hand, hand on the doorknob.

“Merde,” she said. Adam had taught her that that’s what you said to ballet dancers instead of “break a leg.”

She wasn’t sure what to do with the horse, which she had finished the day before with the help of Mara, a curator at work whose help she enlisted out of desperation. Did she set it up on the table for him to come home to after the dinner with her parents? Bring it backstage? Or to the restaurant? She decided to put it in a big shopping bag and bring it along. She could check the bag at the theatre.

I made you something. I don’t have a uterus. Will you ever get a real job? Was there time to front the questions her family would ask? A text? A moment backstage? The subway train bumped along to her scattered thoughts, which followed her through the workday, back on to the subway to her parents’ hotel, to the theatre, to the restaurant. to the restaurant bathroom to which, after the hugs and hellos and Adam beaming –post-show euphoria!!– and her parents beaming–she had a boyfriend!– she immediately escaped, taking her coat and bag with her.

“I’ll order you a house red,” Adam called after her. She saw her mother clutch her father’s arm, in joy or California winery snobbery, or possibly both.

As Patty stared at her face in the mirror she saw her mother’s nose: a nose that would end with her. She sunk down to the floor, even though her mother always said don’t put your purse on the floor in public restrooms because they were a carpet of germs. She pulled the horse out of the crumpled tote bag and set it on the floor and began to turn the crank. The horse began to move in place, his head preening forward and all four legs circling in a silent gallop.

“Cool,” a voice behind her, and a young woman in a short black dress was squatting down beside her. “Did you make this?”

Patty nodded and kept turning.

A tall redhead dressed in a green jumpsuit stepped out of a stall, and seeing them, sat down, cross-legged, in front of the horse.

“Wow!” they said.

Wordlessly, Patty turned the crank toward the woman in black, who began to turn it.

“How incredible,” said the woman in black. “Look at all of those pieces: I can’t even do a jigsaw puzzle.”

“Agreed!” said the redhead, who had pulled off a matching green pump and was massaging one foot. “How amazing that you can make something come alive like that.”

The three of them watched silently, the horse moving in place. There was no hurry, Patty thought, to get back to the table. Maybe she just needed to let the horse run.