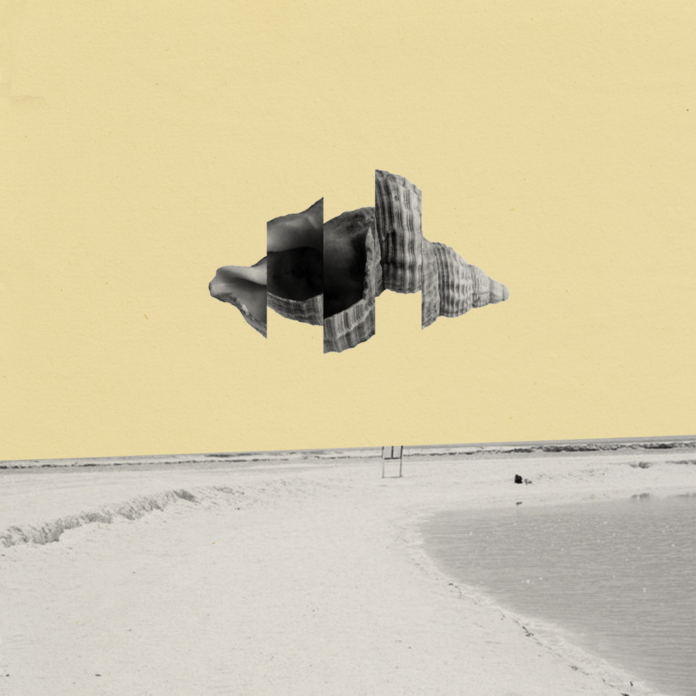

My sister was found as a newborn at the edge of the ocean, washed up on the beach by the tide. She lay on her back with her sea-colored eyes open. She did not cry as the waves surged around her, carrying her little body further up the sand with each foamy swell. Strands of seaweed coiled around her plump belly. In lieu of a parent’s finger, she clutched a shell in her fist—a coiled mollusk spiral, thumb-sized and tapered, as brown as flesh, plucked from the bottom of the ocean.

My parents insisted that Natalie was not found that way at all. They said she’d been born in a hospital, just as I was. My sister was two years older, so I had not been there and could not be certain.

◆

I first formed my hypothesis at the age of eight. We lived in Annapolis then, my father, mother, Natalie, and me. Our house was squat but cozy, and I could see Chesapeake Bay from my bedroom window. Mama and Papa were both psychiatrists, and the similarities did not end there: they were both slight of frame with limp mouse-brown hair, they both wore glasses, and they both routinely left half-empty coffee cups and half-finished books all around the house. When presented with new information, they both responded identically: a pause, a head tilt, and then: “Interesting.” They were so alike I sometimes forgot they weren’t related by blood.

I was both a carbon copy and a combination. Like Mama, I’d developed astigmatism in kindergarten. Like Papa, I was allergic to dogs. Like both of them, I had dark eyes and freckles on every square inch of skin.

And then there was Natalie. At ten years old, she towered over me, nearly our father’s height already. Her shoulders were broad, her hair as straight and blond as straw. A prominent brow. Webbed hands and feet. In family photographs, she looked like a gangly stork accidentally hatched in the nest of stubby sandpipers.

I always knew that Natalie was not like other children. She did not speak. She had no language at all, in fact, neither active nor passive. She did not even know her own name. She spent her days in the playroom, drawing, working with modeling clay, or adhering stickers to her face. She wore diapers to sleep. Though she knew how to use the toilet, she refused to get out of bed to do so.

Natalie was prone to rages, and we never knew what might set them off. A car horn. A stomachache. Nothing at all. Mama had a scar above her left eye from the time my sister hurled a mug across the kitchen. Papa needed stitches when Natalie slammed a door on his hand. I bore so many scratches up and down my arms—always in the process of scabbing and healing—that the kids at school assumed I had cats.

No pets. They would not have been safe with Natalie.

My sister functioned best with a strict routine, which Papa, Mama, and I knew by heart. Always the same breakfast: plain oatmeal and a cup of orange juice. Morning in the playroom with her art supplies. Lunch of peanut butter and jelly and applesauce. Afternoon in the backyard in good weather, or a Disney movie in the living room if it was raining or cold. Dinner of chicken fingers and broccoli. Bedtime at seven on the dot, her star nightlight projecting a whirling galaxy on the ceiling and new age music playing on a loop.

Baths were a hassle. That was my first clue. Natalie had a thing about water; she did not even like the sound of the kitchen faucet running and would press her palms over her ears. My parents had taught her to tolerate being wiped down by a damp washcloth every evening, but Sunday was bath day, a weekly trauma. Mama always sent me to my room, but the screams and splashing carried down the hall. Whatever happened in the bathroom often resulted in injuries—black eye, fat lip.

Once Natalie came crashing into my room on Sunday night, naked and dripping, with suds in her hair. She appeared to have fled in the middle of things, evading the final rinse and the towel. I looked up from my book as she climbed into bed beside me and squirmed under my blanket, soaking the mattress. Her pupils were pinpoints. She rocked back and forth, making the humming monotone that served as her distress call.

Mama poked her head into the room, her hair disheveled. When she saw that I was not in danger, she left again, her back bowed.

Natalie shivered and snuggled close to me to borrow my warmth. I was used to her nakedness; she often decided that her clothes were a nuisance and would strip without embarrassment wherever she was, even in the backyard in clear view of the neighbors’ houses.

I wondered why she was so afraid of the water. I wondered why God had gifted her webbed fingers if she was never going to swim.

“Natalie,” I said, and she darted her blue eyes at me, then away. Words were not words to her—they were music, a sequence of notes without meaning. She communicated best through touch, though you had to let her initiate. If you patted her shoulder or stroked her hair when she wasn’t ready, she often bit.

She continued to rock gently against the mattress. The steady, repetitive movement reminded me of the buffeting of waves in deep water. After I’d spent a long day swimming in Chesapeake Bay, I would feel a phantom echo of the surf’s constant motion for hours afterward. Natalie hummed, and this, too, reminded me of the sea: a muffled warble, the way human voices sounded underwater.

She reached for my hand and laced her fingers through mine. I felt the webs between her fingers stretch against my knuckles, and that’s when I got my idea.

◆

At school, I researched mermaids. The library was the best part of the pricey private academy my parents had chosen for me. Heavy mahogany bookshelves stood interspersed with stained glass windows. The light was diffuse and marbled. A reverent hush filled the air, broken only by the scratch of students taking notes.

I hefted a stack of books into the seclusion of a carrel. Turning the pages, I read that nearly every culture had developed legends about mermaids. Some people saw them as good omens or benevolent spirits, while others believed they were dangerous. In China there were stories of mermaids who wept pearls instead of tears. In Zimbabwe they were called “njuzu” and got blamed for foul weather. The Greeks pictured them as malicious sirens, luring sailors to their deaths for sport.

Scientists theorized that manatees were the root of the myth of the mermaid, though the photos on the glossy page—lumbering gray beasts with whiskers—looked nothing like women to me. But then, I was not a sailor who had been at sea for forty days on a ship crewed entirely by men.

According to the book, mermaids never appeared in human form. They always had long fish tails, sometimes gills too. The only story I could find of a complete transformation was The Little Mermaid, a horrifying cautionary tale in which a mermaid traded her voice and tail for human legs and feet that felt with every step as though she were walking on broken glass.

None of this sounded like Natalie. Discouraged, I put the book back on the shelf and went to lunch.

I had known most of my classmates since kindergarten. The school was a small, intimate affair. Patsy, Ellie, and Aliyah and I always sat together, proud third-graders, no longer relegated to the little kid area of the lunchroom with its rainbow chairs and constant supervision.

My friends often had playdates at one another’s houses after school. I was sometimes invited but rarely accepted, since it would have meant leaving my parents with Natalie for an extra few hours without the relief of my presence, rendering them irritable and spent. Besides, I could never reciprocate by asking Patsy, Ellie, or Aliyah over in return. No one but my parents and I ever crossed the threshold of our house; we did not know how Natalie would react.

I did not particularly mind this. I found my school friends nice but overwhelming. They laughed so easily, so loudly. Their movements were unguarded and uncontrolled; Natalie would have smacked me if I ever gestured as freely as Patsy usually did. Aliyah and Ellie were criers, bursting into sobs while describing a sibling who would not share or a parent who had punished them by taking away their video games. I often failed to react to the crowning climax of this kind of sob story, expecting that there had to be more to come. Such minor things—big sisters who hoarded cookies, little brothers who wore diapers and stank—did not merit tears.

I was the quiet one. There was no point in talking about my home life. My friends would not have known what to do with stories about Natalie rocking and humming for hours on end or gouging her fingernails through the flesh of my forearms because I dared to leave the room before she was ready to be parted from me.

◆

Every Sunday morning, my mother and I walked the two and a half blocks down the hill to the beach. It was our special time together. There was never enough to go around in our house—Natalie was a whirlpool that sucked up all the light and energy and love. But for two hours on Sunday morning, Mama belonged only to me.

It was March then, too cold to swim. The summer tourists, thankfully, were not yet present. Mama and I took our shoes off and strolled side by side on the chilly sand, not saying much. I picked up sea glass and showed it to her. The beach was bordered at each end by a pile of stones, each rock bigger than I was. Sometimes seals gathered there, sunning themselves.

“Do you believe in mermaids?” I asked my mother. The wind was icy, whipping my hair against my face and buffing Mama’s cheeks rosy.

She considered my question. “As symbols of men’s idealization of the feminine, yes. Mermaids might also represent a fear of women.”

“Okay.”

“I suppose they could be seen as emblems of female empowerment. It depends on which myth you’re thinking of.”

I nodded, feigning comprehension. My parents did not childproof their conversation for me, which gratified me even when I struggled to understand. They treated me as though I, too, were a trained psychiatrist.

And then my mother grinned. “I always liked selkies better, though,” she said. “They make a much more interesting story.”

“Selkies?” I did not know the word.

“I’ll tell you on the walk home,” Mama said. “Your father has been on Natalie duty for almost three hours. I’m betting he’s at the end of his rope.”

◆

That night I lay awake, blazing with new ideas. My sister was a selkie. I’d come close with my hypothesis—I had just chosen the wrong mythical creature.

Mama’s people were Irish, and in her childhood she’d been told about selkies by her grandfather, who had died before I was born. Selkies were chimerical beings, part human, part seal, morphing their biology when they crossed from water to land. In the ocean, they swam and frolicked with other pinnipeds. On the shore, they shed their pelts, peeling off the heavy fur and tucking it somewhere safe, out of sight. They looked like people then, moving through the human world unnoticed.

Selkies were neither one thing nor another, living a halfway existence, always yearning for their other state of being. You could befriend them in their human shape, even love them, but you could not keep them. One day the call of the sea would overpower them, and they would return to the beach where they first had come ashore, find their hidden sealskin, change their form, and swim away.

Mama had never seen a selkie herself, but she told me that her grandfather had. It was a brief encounter, a distant glimpse along the Irish coast. My great-grandfather was a young boy then, watching from a clifftop as a woman picked her way over the rocky shoreline far below him. He saw her stoop and gather something up off the ground—he couldn’t tell what it was. A moment later, a seal lolloped over the stones and dove jubilantly into the waves.

◆

On a sunny afternoon, my sister and I sat at the playroom table, drawing together. The first rule of Natalie was that she could never be alone. In part, this was her own choice—she became distressed without one of us in sight—but it was also a matter of safety. What if she marked up the walls with her crayons? What if she figured out how to open the window and climbed out?

So I was on Natalie duty while Mama saw clients and Papa prepared dinner. My parents shared an office on the east side of the house and took turns meeting their patients there. I’d only visited their workspace a few times—plush leather chairs, a spidery fern, ochre light, soundproofing, and a white noise machine for good measure. The room had its own entrance where clients could ring a private doorbell and go in and out unseen by Natalie and me.

I was teaching myself to draw seals out of a book. The tricky part was the snout—I kept giving them dog faces. Natalie drew spirals, her favorite shape, swiveling her whole torso with each rotation of the crayon. The walls of the playroom were papered with her artwork. Mama and Papa wanted her to feel that her efforts were as valued as mine—my A+ essays on the fridge, my chess trophies on the mantel—though I knew Natalie did not care. Drawing was an experiential need for her, and as soon as she finished each page we might as well have lit it on fire.

After a while she became interested in what I was making. I’d mastered the seals now, getting the faces right, as well as the low, frontal placement of the flippers, which initially I’d drawn too high, mid-torso, like fish fins. Natalie leaned close to me, breathing sticky breath on my shoulder. She could draw with great precision when she chose; she’d gone through phases of sketching crisp five-pointed stars and multicolored flowers in the past. I’d taught her how to do both.

Now she held out her hand, asking me to teach her this, too. We had our own method. She placed the tip of her crayon against the paper, and I grasped her wrist and guided her through the bulbous outline, the strong tail. Again and again I rendered the shape, using Natalie’s whole hand as my drawing instrument.

Gradually she began to take charge of the easy parts. She would make the curve of the belly herself, then let her arm go slack so I could do the complicated face. Each time we sketched another seal, Natalie did more of it on her own. At the end, my fingers lay lightly on her wrist as she drew the animal without any help from me.

It occurred to me that no one watching us would have been able to tell who was in control of the work at any one moment. In silence, through my sister’s language of touch, we’d communicated privately and perfectly.

◆

That night over dinner, I asked Mama and Papa for details about Natalie’s birth. They were tired, distracted. A vaginal delivery. Unmedicated. No, she wasn’t adopted, why on earth would I ask that? Natalie gobbled her food and pushed my father’s hand away when he attempted to wipe her face clean with a napkin.

As Mama washed the dishes and Natalie sat with her palms against her ears to block out the sound of the water, I pulled my father aside and probed for more specifics. Was there anything he and Mama had not told me about my sister? Anything mind-blowing or life-changing? A walk along the beach one day, perhaps, back when they were a childless couple yearning for a baby? An unexpected gift on the sand?

Papa seemed to focus fully on me at last, pushing his glasses further up his nose. I thought he was about to admit the truth—a foundling child, a seal pup missing its fur.

But instead, he began to explain the mechanics of human reproduction, something he had covered in excruciating detail years before. Sperm and egg. The placenta. Apparently he thought I was hinting that I wanted a refresher course.

“That’s not what I meant,” I said, but my father had already gone to get a notepad to draw some diagrams, and there was no stopping him now.

◆

The school library possessed scant information on selkies—this was Maryland, not Ireland—but a dusty encyclopedia on a back shelf offered a few details I hadn’t yet heard. There were legends of selkies who lost their sealskins and could never return to the water. Bereft, they would wander the shore, unable to change back into their oceanic form.

Sometimes it was their own fault; they had been careless in hiding their pelts, which were then taken by unwitting trappers or eaten by animals. Sometimes they stayed too long in the world of humans and forgot where they’d come ashore. There were even stories of men and women (usually the former) who found a selkie skin and hid it on purpose, then married the poor landlocked creature.

I slammed the book shut in alarm. Something like this must have happened to Natalie. Mama and Papa would never have hidden her sealskin intentionally, but they might not have known what it was. I imagined them plucking the infant from the surf. I imagined them wrapping my sister’s damp body in one of Mama’s fine silk scarves. Perhaps, off to the side, a dark shape lay on the sand, rumpled fur and a gleam of blubber. Mama and Papa would not even have noticed it. They would have hurried home with the child in their arms, never realizing what they had left behind.

◆

My parents often talked late at night. This was something I knew without entirely knowing it, the way children do with information that is too difficult to absorb. I often half-woke to hear raised voices in the kitchen. They cried—sometimes Mama, sometimes Papa—and said Natalie’s name. Never mine.

The weather warmed. When Mama and I walked to the beach on Sundays, I splashed through the shallows, wondering exactly where Natalie had floated ashore. Did my sister have another family out there in the deep water? Had her selkie parents lost track of their little seal pup, not noticing as she swam too close to the land and transformed without meaning to, shedding her precious pelt? I imagined her parents—her real parents—crying for her all around Chesapeake Bay. Maybe she even had siblings.

Natalie never came with us to the beach. Mama had told me that she’d brought my sister here when she was younger, but Natalie screeched if even a crumb of sand clung to her skin. She refused to look at the ocean, much less approach the water. Eventually Mama gave up.

In truth, Natalie hardly ever went anywhere anymore. My parents used to take her to the park or the nature preserve, back when she was little enough to be caught and physically restrained if she ran off or attacked another child. Now, though, she was too big, too strong. Besides, any deviation in her routine caused disruptions to her nervous system; she could become more violent. It was best for everyone if she remained confined at home.

Sometimes I tried to approach the seals that lay heaped on the stones at the edge of the beach, basking in the sun. Mama did not pay much attention to what I did. Her dark eyes sought the horizon, and her gait often faltered. She would stop and let the waves wash over her feet as though she did not have the wherewithal to move on.

The seals ignored me when I spoke to them, just as my sister always did. I asked them about Natalie, about her lost family, but they only slumbered and snorted. I knew better than to get too close; the seals would not like it any more than Natalie, and they had razor-sharp teeth.

◆

Back home, I found the shelf where Mama stored the photo albums. The first snapshot in my baby book showed me in a hospital basinet, swaddled in a standard-issue, green-striped warming blanket. The first photo in Natalie’s baby book, however, showed a damp newborn curled on Mama’s chest against the backdrop of our own front porch. In the picture, Mama’s expression was not proud or exhausted but startled, staring down at the child in her arms as though she had never seen such a thing before. My sister’s eyes were open, white-blue, unfocused. Her fingertips were pruney—from the amniotic fluid in the womb, Papa would have told me, but I knew it was really from the sea.

My theory was faultless. Everything about my sister made sense when viewed through this lens. Her rocking, which baffled strangers, was an attempt to replicate the surging of the current. She preferred to be naked because seals were naked. She did not speak because seals did not speak. Her nonverbal vocalizations—humming, gurgling, a high-pitched squeal—would no doubt have been perfectly understood underwater by others of her own kind. She threw tantrums because she had misplaced part of herself; she must constantly ache for what she had lost. Her webbed fingers and toes explained themselves.

Her dislike of baths and faucets, too, was as natural as could be. Without her sealskin, she could not transform. Water surely felt odd against her human skin, unpleasant and unfamiliar. It must have evoked the enormity of her deprivation. The hiss of the kitchen sink, the meager trough of our little tub—these things were paltry echoes of the wide ocean, a perpetual reminder of Natalie’s imprisonment in our realm. Trapped, marooned, and halved.

◆

Everything changed on an ordinary day in April. It was snowing, the last snowfall of the season. Natalie and I sat in the playroom as Papa saw clients and Mama nursed a migraine, lying in bed with a wet cloth over her eyes.

Natalie was in one of her moods. She kept growling as she drew angry spirals, wearing her red crayon down to a nub. She crumpled up each page when she was done and hurled it to the floor. I got to my feet, thinking about my homework. Aliyah and I were partners in a presentation about bats. I was in charge of research, while Aliyah, a natural performer, would do the talking in front of the class.

Natalie screeched at me, forbidding me to leave the room. I told her I was just going to get my science folder; I would be right back. We all did that, Mama and Papa and me, telling Natalie things even though we knew she did not understand.

The next part is hazy in my memory, permanently blurred by the concussion. I hurried past Mama’s closed door toward my bedroom at the end of the hall. As I passed the top of the staircase, there were footsteps behind me. Something slammed against the side of my head, and I woke in an unfamiliar white room.

◆

I remember pieces of my recovery. Either Mama or Papa was always at my bedside, helping me to the bathroom or paging the nurses to get me more medicine for the pain. They both stared at me with the same haunted expression, their faces etched with lines that appeared to have formed since my hospitalization. They looked more alike than ever before, twinned by their remorse and misery.

Gradually I learned what had happened. Natalie hit me while I was off-balance, walking past the stairs, and I fell all the way down to the first floor. Mama woke from her nap to my sister’s wails and found me unconscious. She thought at first that I was dead. She interrupted my father’s session—an unprecedented event—so that he could deal with Natalie’s hysterics. Mama rode with me in the ambulance. I spent three days in a medicated coma as the swelling in my brain went down.

Natalie did not visit me in the hospital, of course. When I asked about her, my parents patted my hand and changed the subject. I remember a series of tests: naming colors, pointing out shapes. I remember that my head ached all the time. The concussion had worsened my already poor vision, and I needed a stronger prescription for my glasses now. I got winded just walking down the tiled corridor of the hospital wing. The doctors explained that I’d lost a startling amount of muscle mass in the brief span of my inactivity.

My friends from school sent a get-well card that sang a tinny message. The nurses rumpled my hair and told me I was a wonderful patient. It was strange to be the center of everyone’s attention. I felt a little guilty about the stares and smiles, as though I was using up a finite, precious resource that must be needed elsewhere.

I left the hospital on a warm day in April and stepped into a world alive with spring, every flower blooming, the air scented with pollen. The seasons had changed while I recovered. I came home to find a celebratory banner hung in the living room, a bouquet of flowers from my teachers on the kitchen table, and all my sister’s things packed into boxes.

◆

Children accept the world they know. At the age of eight, I was accustomed to a state of being in which my parents never went out or had a night to themselves. My friends had babysitters; I did not. I was used to dabbing my wounds from Natalie with hydrogen peroxide and applying bandages on my own, without complaint. It was my job to love my sister and care for her, no matter what it cost me. I never questioned that. It was my job, too, to help my overburdened parents in any way I could, supervising Natalie so they could shower or cook a meal, accepting her violence without blame, and never asking them for anything myself. I understood without ever being told that I needed to be smart and successful, a source of pride for my parents and a counterpoint to my sister. I needed to be easygoing and agreeable, too, showing my parents that Natalie was not too much for me, that I could handle it, all of it. It never occurred to me that there was any other option—for my sister, for my parents, or for me.

Now, of course, I know better. Even before my fall down the stairs, my parents had often discussed putting my sister in an institution. That was the subject of their anguished late-night conversations, debating both sides of the issue, my mother reversing her stance, my father playing devil’s advocate, going back and forth until one or both of them wept. They’d made calls and done research, once going so far as to tour a facility in western Maryland before changing their minds. Now, looking back, I understand the terrible math they could not solve: black eyes for them, a real home for Natalie, no vacations or trips or even a night alone together, security for Natalie, scratches on my arms, comfort for Natalie, my childhood constricted and curtailed and diminished, a sibling for Natalie.

My stay in the hospital tipped the scales. I don’t remember how my parents explained it to me; my head was still fuzzy then. I do remember crying and begging them not to send Natalie away. I could not imagine my life without her, I said. At this, my parents exchanged a glance, one of those knowing looks that communicated a great deal.

“It’s best for both of you to forge a separate identity now,” Mama said.

“We don’t want you to become an undifferentiated ego mass,” Papa said.

“That’s right,” Mama said. “Codependency isn’t a panacea.”

My temples throbbed. All I could do was nod.

◆

I did not sleep for most of Natalie’s last night at home. This was partly the fault of the hospital—I was still readjusting to a normal circadian schedule and an unmedicated brain. But mostly it was grief. Natalie did not know what was about to happen to her. We could not explain it. She was irritated by the presence of the boxes and her inability to find her toys and art supplies, but Mama and Papa were letting her watch TV as much as she wanted every day, so she was happy enough.

In the morning, Papa would drive her across the state, and I would see her on holidays, maybe. Tears welled in my eyes. Mama had shown me the website for the facility. Smiling children waved in front of a brick building, dressed in tie-dyed T-shirts they’d presumably made themselves. They were all different ages and races and sizes, yet they all had faces like my sister’s, though I couldn’t pinpoint exactly what in their disparate features overlapped. They had selkie faces.

Before dawn, before the robins even began to sing, I crept into my sister’s room. Natalie was awake too, sitting up in bed with both arms raised as her nightlight spun on the bookshelf, projecting stars across the wall and her skin.

“Come on,” I said. “Let’s go.”

She did not want to put on her coat. She kicked me as I laced up her shoes. She stepped through the front door as though it were a portal to another world, stroking the knob and the deadbolt curiously with her fingers. When was the last time she’d left the house? I could not remember.

I held her hand as we walked down the hill to the beach. Natalie let me, though she usually hated persistent skin contact. The sun was rising on the other side of the ocean. I expected my sister to throw a tantrum over the change in her routine or to balk at the overstimulation—seagulls crying overhead, a motorcycle whizzing down the road, airplanes crisscrossing the sky. But Natalie was surprisingly docile, clinging to my fingers and gazing around in evident awe, her azure eyes wide.

She stopped dead at the edge of the sand. A cool breeze blew off the water, lifting the greasy strands of her hair away from her face. Mama and Papa appeared to have given up on Sunday baths. A few seals lolled on the distant rocks, soaking up the morning rays. Their bodies were as round as eggs, dappled with spots. One of them lay on its side with a single flipper sticking straight up in the air.

I pointed to the seals. “Those are your sisters,” I told Natalie. “Your other sisters.”

She let me lead her onto the beach, step by cautious step. Her lips parted in amazement at the squish and slide of the sand beneath her shoes. The sun rose, bejeweling the water’s surface with light. I guided my sister toward the waves without pulling or insisting. I touched her as gently as I did when she had mastered a new drawing on her own but had not yet removed her hand from mine. Together we crossed the midline of the beach. High tide had come and gone, leaving shells and whorls of seaweed on the brown, compact sand.

“Do you remember where you left your sealskin?” I asked. “They’re taking you away today. Away from the ocean. This is your last chance.”

Natalie took another step toward the water. In the distance, one of the seals broke away from the others and gallumphed noisily into the surf. My sister did not appear to notice. Her gaze was fixed on the shimmery shallows ahead of her. The waves glided up the beach with a delicate hiss, and a bubbly spume skimmed the toes of Natalie’s sneakers. I expected her to scream or bolt, but instead she smiled.

I had rarely ever seen my sister smile. I’d never heard her laugh.

I glanced back up the hill toward the house. We didn’t have long. Any minute now, my parents would wake and find us missing. Maybe they would call the police. Maybe I would be punished for the first time in my life. Would my parents even know how to do that? I’d never broken a rule before, never said “No” to anything they asked of me, not once.

Natalie knelt and spread out her hands, the webs between her fingers catching the light. She laid her palms on the surface of the water, making tiny ripples, feeling the heave and swell of each new wave. Soon she would be taken from me, packed along with her boxes into the back of our minivan and driven out of sight. I could not imagine what would happen after that. There was only a strange void when I looked ahead to a life without her—wild, sharp, unwanted freedom.

“We need to find your sealskin,” I said. “Did it wash up here on the sand with you? Or over there by the rocks? Think, Natalie. This is important.”

She was still smiling. The expression sat oddly on her angular face. Her palms dimpled the silver veneer of the sea.

I left her there and darted down the beach. I was certain that my sister’s lost pelt had not decayed during her ten years on land. In the stories, selkies sometimes hid their skins for decades before retrieving them unharmed. I poked into the crevasses between the rocks with a stick. I dissected a clump of seaweed, glancing over my shoulder to check that Natalie was all right. She was.

It had to be here somewhere—a charcoal-colored scrap of fur just big enough to swaddle an infant’s body. The tourists wouldn’t have taken such a strange item; they were like magpies, attracted by shells and pretty stones. No animal would have eaten it either. There were only seals here, and they would understand the significance of that precious object. I checked under rocks and uprooted half-buried driftwood. I investigated the gaps between the rusted beams of the pier.

I did not find Natalie’s sealskin before a scream broke the air and my parents came running down the hill, red-faced and breathless. I did not find it before my sister was forced into the car, yowling, leaving scratches on my arms, her final goodbye. I did not find it that summer, though I searched the beach every time Mama and I visited the shore, Papa joining us now, no longer tethered to home, the two of them strolling hand in hand. I looked for my sister’s skin when my friends and I played at the shore together, Aliyah and I each wearing one half of a heart around our necks, Patsy showing off her handstands. I looked for it the day I asked Papa when I could visit Natalie and learned that it would be a while; my sister needed time to adjust to her new routine, her new surroundings, and my presence would only destabilize her. In the fall, maybe. Or next year. I looked for her sealskin after my first real birthday party with friends, nine years old, and we actually lit the candles because there was no danger of Natalie tipping the cake over and setting the house on fire. I looked for it after a photograph of my sister bloomed overnight on the institution’s website, her flaxen head bent over a sheet of paper, drawing a seal with a rotund belly and perfectly placed flippers. I took my first-ever babysitter, a high school student with pink hair, to the beach to help me search after Mama and Papa went out on a date, him freshly shaven, her unrecognizable in lipstick and a low-cut dress. We scoured the sand for an hour, and then I came home and sat cross-legged in Natalie’s empty room, the walls bare and washed in sunlight.