It’s like an apartment building with the walls removed. People all turned inward to their campfires, their picnic tables, even during the day, when you’d think they’d be out fishing or swimming or something. They just sit there on a patch of dirt, poking a fire or cracking open cans from the cooler. And some of them look like they really plan to stay a while, with their flowered tablecloths, clotheslines strung up between the trees. One of them has what looks like a bird cage on the picnic table. Another has a bright plastic playpen set up next to their car. With a puppy inside it, or maybe a baby, he can’t look long enough to be sure. Charlie averts his eyes when he walks by. Doesn’t want to be rude.

Charlie’s back at his own site now. He’s just going to sit here a while, try to find some peace. The world is so bright it looks bleached today, and he’s thirsty. No point in drinking water, it doesn’t do any good. He should make some coffee but first he just has to close his eyes, block out the light for a while. Rest. But somebody not far off is calling the name Maddie, Maddie, like they’ve lost someone. A little girl probably. Who loses their own kid?

The next site over was empty when they left for the lake this morning but now there’s a huge black SUV and bicycles of every size leaning up against it, for the whole family of what—ten? And the RV on the other side of them has a generator that fires up every now and then, as loud as a dump truck. The smell of diesel wafting around. They even have an awning at the door of the RV, and a green carpet, indoor/outdoor. Why not just rent a hotel room? Isn’t camping supposed to be for outdoorsy, quiet type people?

Camping is just cheaper. That’s why he and Julie come to these places every summer, because they can’t afford to rent a house on the beach, or a nice cabin with actual walls, with a bathroom they don’t have to share with a hundred other people. State parks are cheap. They attract these crass, noisy people and their crass, noisy children, who don’t actually like the outdoors but can’t afford something better. That’s me, I guess. Guilty as charged. But aren’t those SUVs expensive? Those campers and generators? Charlie sure can’t afford a big new SUV. So maybe it’s not money these people lack. And maybe they actually like camping in state parks, surrounded by other people and their gear and their noise.

Now they’ve got a few voices calling. Kids, it sounds like. Maddie, Maddie. It’s turned into a game of hide and seek. It’s hard to tell if they’re distressed or if this is normal for them. People here are just loud. Whatever they do it’s loud, like they don’t realize they’re out in the open and everyone can hear them. Especially at night. You can’t believe how clearly voices carry across a campground after quiet time. Usually campgrounds are pretty empty during the day, but here it seems like the people are hanging out in their sites all day long. Maybe he’s just never been around all day to find out. Usually he’s down at the lake or whatever.

He probably should not have stomped off like that, leaving Julie with the kids on the cruddy beach. But he was so exhausted, and she’s the one who loves this stuff. Lakes and trees and eating outdoors. Why did she insist that he join them in deciding whatever they were going to do? He just needed to rest somewhere. Anywhere. That’s all he wanted, but she kept needling, but what do you want to do? She wanted him to have fun too, was adamant about it. But you can’t insist on fun. Especially for a person who got no sleep last night, and the whole week leading up to it, his whole life even, it felt like. But he was trying, he really was. Trying to sleep and trying to live. Couldn’t she see that? Finally he just left them to figure it out themselves. You guys do what you want. I’ll see you later. And he walked off. Didn’t even look back.

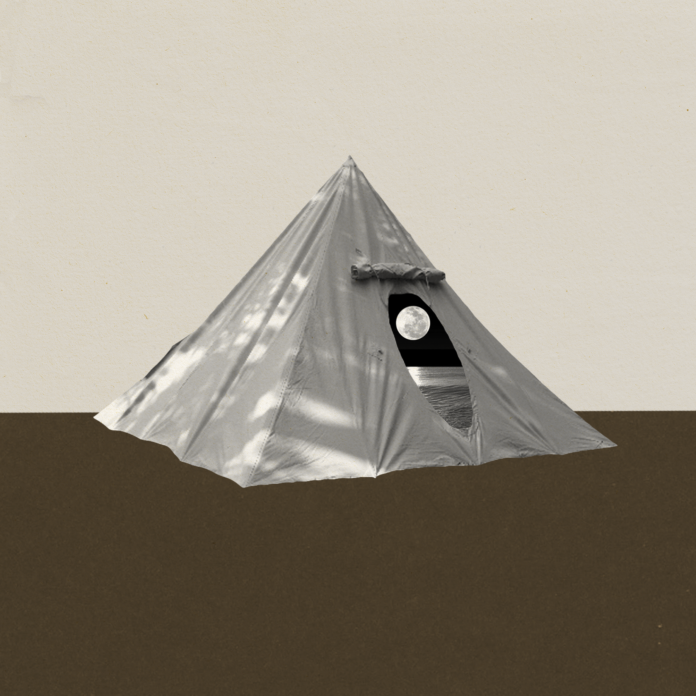

And now here he is, alone in the campsite hoping for a little quiet, but no. The tent is stiflingly hot in the midday sun, so he can’t lie down in there, and it’s no use anyway. You can just feel all the people around you. All the voices, and the car doors opening and closing, the chirp of car alarms. And keeping a fire going is a noisy business. The constant snapping of twigs, axes thwacking into logs, or the rustling of long branches being dragged out of the woods. And now somebody’s turned up their music, as if the whole campground wants to hear it. Classic rock. Of course. An actual radio with a DJ. Charlie can’t make out the words but he knows the routine, the DJ making jokes on a hot summer afternoon, fry an egg on the sidewalk. Who are these people? He doesn’t know anybody who listens to this stuff anymore.

There they are again. Maaaaaaaaddie! Two sweaty kids run past, calling. They’re having fun, he can tell. Tagging each other. Excited to have something to do. Screaming her name: Maddie!

Charlie just wishes they’d be quiet in their games. Or if the kid is really lost, maybe they could be more serious about it. Get the state park officials over here. Ask the people one by one if they’ve seen her. All this running around and kids shouting will just encourage Maddie to make a game of it. He’ll never understand other people’s fun. He just wishes they didn’t have to be so loud about it.

He finds the graham crackers and tears open the package. He shouldn’t eat these right now but maybe the sugar will help. It’s easier than firing up the stove, making coffee in the old-school percolator. And these are sweeter than they look, even if a bit dry. Sweet helps when sleep is impossible, though it’s not what the doctors recommend. Sleep hygiene, they say. As if a gentle little routine could knock him out when the most powerful drugs can’t do it.

Once he got going this morning he thought today might work out okay. When they were walking down to the beach after breakfast, after he’d had some coffee, used the bathroom in relative peace, he felt kind of all right. He figured he’d just lie on the sand, relax a bit while the kids went swimming, Julie content to keep an eye on them, read a little of her book maybe. He thought he could do it. It was a long walk down to the lake and the bag was heavy with a day’s worth of food, water bottles, towels, but he offered to carry it. He could be a good guy like that. He carried it all the way down, not complaining. It was the four of them, with all their pool noodles and water shoes and sunscreen, finally ready for their day at the lake. It might’ve been all right if he could’ve just lain down in the warm sun and closed his eyes.

But the beach was crowded, there was a sulfuric smell coming from somewhere. There were children fishing with bobbers off the dock in the swimming area, throwing their hooks around. He could see Julie was disappointed too, but she wouldn’t give up on her camping, on her fun. She tried to rally him, to rally all of them. Okay, so the lake is kind of crowded and gross. We probably don’t want to swim here, but we can still have a good time! What do you want to do? Should we rent boats, paddle boards? No, no, he said. What, then? Do you want to go to a different lake? She got out her phone. There’s another lake nearby, maybe it will be better. But he couldn’t. He just couldn’t. He had no more energy. They were here, this was all they got. He just needed to relax, to rest, was capable of nothing else. And Julie just wanted to do, do, do. And the kids, they didn’t seem to notice one way or the other, just expecting the problem to solve itself. Expecting their parents to fix everything for them, like always.

Just do whatever you like, Julie, he said. But she’d never just say what she wanted. It was always everybody else first. I don’t know, she said. I guess we could get a paddle boat. Or we could try to swim, if we go farther out, away from the beach. Or maybe hike in the woods? On and on. He just needed it to stop. To be left out of it, whatever it would be. Was that so much to ask? She was getting frustrated, he could hear it in her voice, and the kids weren’t helping. Elise didn’t care, she just wanted to do something, and Evin wanted to hurry up. Come on, you guys, we’re wasting time. But Julie just kept insisting. Honey, really, we’ll do whatever you want. We can go to a different lake. I’m sorry this one isn’t so great. But he was not going to be happy. They needed to just leave him alone, do what they wanted, he didn’t care. He hadn’t slept at all last night. He was hoping for a couple hours, just one or two, but no. Nothing. She couldn’t possibly understand what that was like. So she’d pushed him into a corner till finally he just said, Forget it. I hate this. This is my last camping trip. I’m never doing this again. And he left. He walked away. Such a relief to walk away! She stared after him, he’s sure she did, a pained look on her face, but she’d figure it out. She didn’t need him. She and the kids had their sleep, they’d have their fun.

There’s no way he’s going to rest here either, though, not in that tent, not with that noise. At home the bathroom is a place you can relax, turn on the fan, people leave you alone, but not here. The bathroom here is disgusting. Wet toilet paper on the floor and globs of toothpaste in the sink. Julie says the women’s bathroom is fine. Of course, she always says everything is fine, but women don’t pee on the floor, at least. How is it vacation when you share a bathroom with a bunch of men, and why are men such pigs? It’s easy for Julie. Everything’s easy for Julie. She lies there sleeping all night long, snoring softly, while he’s tormented by every last sound, every thought. You’re supposed to hear things like loons and owls at night while you’re camping, but last night it was just car doors slamming, or someone walking to the bathroom in flip-flops, their feet smacking and the gravel crunching all the way.

He’s nearly finished a whole pack of graham crackers, eating them one after the other like they might save him. They’re not even good. But the edges of things are starting to blur a bit. He could maybe just put his head down, drift off a while.

Maddie! Where are you?

Jesus. They’re coming closer. It’s like these people are closing in on him. They’re tramping through the woods now, not even using the paths, crushing the ferns there. The snap and crackle of branches breaking. Maaaaaaaddie!

No wonder they don’t know where their kid is. So many of them out there unsupervised with their fish hooks, their kayaks. Packs of them on bicycles, whipping around the loop, faster than the cars, howling like it’s the best fun ever while the drivers swerve and slow down even more. Tormenting adults, that’s what those kids are doing. No wonder kids like camping. They get away with all kinds of mayhem, their parents too tired to care. Their parents doing whatever it is they do at their campfires all day long. Drugs, maybe. Feeding their pet birds and listening to the Eagles. “Hotel California,” of course. Charlie’s pretty sure they’ll be playing that song on repeat in hell.

They’ve moved away again now. Back out on the road, moving toward the next loop over. Good. He tries to ignore the feeling of an ant crawling up through his leg hairs. He slaps at a mosquito. Of course. Those too. Mosquitoes. What is the point of all this?

Julie said, you should stay home if you’re tired. I know it’s been rough lately. I’ll take the kids and you can just use this time to rest up. She seemed all kind and understanding, but also she was saying we don’t want you to come. He should’ve taken her up on it, but he didn’t want to be that guy, the one who stays home or ruins the fun. And he thought this time would be different. He was prepared. He had a precise concoction of meds, new earbuds, his pillow from home. If they had more money, if they were willing to rack up more credit card debt, they could go somewhere better, but they don’t. They can’t. And now he gets to be the guy that ruined the camping trip again. Why does she corner him like this? And in front of the kids. Not that they ever seem to notice.

The thing is, he’s always hated camping. He told her that before they even got married. I’m not the outdoor type. But Julie loved it as a kid herself, and now Elise and Evin seem to like it too, at least once it’s over. I guess that’s what they mean by making memories. Right now it’s torture, but years from now the kids will be like, hey, remember that time we were out on the lake in the paddle boat and the thunderstorm blew in? Remember when Evin dropped the whole bag of marshmallows into the fire? It will become family lore. You have to put up with some inconvenience in the present in order to get a good past. If you just stay home there’s no story. Remember that time we watched Aladdin again? Who ever says that? He can barely remember what he watches one week to the next, but surely he’ll remember the smell of marshmallows blowing up then blackening, he’ll remember the bird cage on the picnic table. At least that bird was quiet last night, not rattling off swear words or Polly-wanna-cracker. Probably they throw a cloth over the cage at night. Too bad you can’t do that with people. He’d like to take a huge cloth and cover this whole place up and let everyone get some sleep.

One time in Maine he could hear the two guys in the site next to theirs talking all night long, crunching beer cans and tossing them into the fire, one after the other, as their conversation got louder. Oh, yeah, she wanted me to do anger management, the one guy said. No fucking way! There was talk about guns too. He didn’t catch the whole story, just words now and then—automatic, my wife, fuck this, fuck that—enough to make him decide not to go over and ask them to please keep their voices down. He just waited them out past midnight, 2 am, 3. Finally he drifted off or they got quiet, he’s not sure what happened first. It was probably four in the morning, with first light at five and everything stirring again. That’s the kind of memories Charlie is making.

Last night could’ve been okay. Everything was set up just right. He had the white noise playing on his phone, earbuds secured with a bandeau. He could feel his consciousness letting go, the pills kicking in, a warm wash over his mind, but then—bam!—he’d be jolted awake. A car door would slam, then prowl slowly around the loop, its headlights flashing across the walls of the tent. He could even hear other people’s tent zippers opening, as if it were magnified somehow by the cool night air.

Other times he drifted off he supposedly started snoring. And there would be Elise, leaning over her mother’s bag and nudging him, whispering, Dad, Dad, you’re snoring! It was a kind of torture. His air mattress, already pretty thin, was flat by morning, and everything was wet, even though there was no rain. Julie was up early, smiling and making coffee on the Coleman stove. A noisy business. Good morning, Honey! At least the coffee was good and hot.

“Hey! Have you seen a little girl?” Charlie lifts his head. There’s a guy at his campsite now, right in front of him, standing there in cutoffs and a muscle shirt. Sweaty. A tough looking guy, a tattoo all the way up his leg and camo Crocs. Was Charlie asleep? Did this guy see that Charlie was asleep?

“She’s wearing a pink T-shirt. Shorts. About yay big.” The guy holds his hand up just above his waist.

Two little kids are with him, talking over each other. “She went to the bathroom,” “she went to the playground.” “She was wearing a pink shirt with the Pretty Pony on it.” “No, the Surf City shirt!” “Have you seen her,” “have you seen her?”

It’s startling. To have people looking at you like this, like they came out of a dream or something. It certainly wakes him up for a second. He has to get it together. How embarrassing, to be sleeping on the picnic table. But was he actually sleeping?

“Sorry,” he manages. “Wow. So. Yeah, I’ll keep an eye out. What site are you in, if I see her?”

“Willow. One of the lean-tos. Thanks, man.” And he walks off, the two kids calling her name again, all the way around the loop. He hopes they didn’t notice the graham cracker crumbs stuck to his cheek, all the empty wrappers.

What if the kid is really lost, drowned in the lake or something? Then what would they do? The whole campground would probably be shut down. They’d dredge the lake. Send dogs into the woods. He should get it together, try to help. There’s a missing kid and he’s just been thinking it was a joke, worrying about himself.

Maybe he’ll walk around in the woods a bit, see if he can find her, a girl in a pink T-shirt. But won’t that be weird, a grown man, wandering in the woods like that, looking for a little girl he doesn’t even know?

He’ll look for kindling at the same time. He’ll pick up some sticks for the fire later and look for the girl. See if she’s hiding behind a rock. And if he finds her, he’ll be a hero. Maybe then his family can stop being mad at him. They’ll forget the whole scene at the lake and be glad he came with them. Thank God you were here, Charlie! Everyone will be saying it.

The man and the little girls are out of sight now, but he can vaguely hear them calling. Nobody in the other sites seems too concerned. Maybe it’s not an emergency. Maybe this is just normal camping behavior. He really can’t tell. His judgement is warped and his body is wrecked and it’s only supposed to get worse when he gets old. If he manages to live that long. Insomnia shaves years off your life, they say. These pills might help, they say. But nothing ever does, not for long.

Other people are just going about their business. The middle-aged guys on the end drag a whole tree out of the woods, whooping and hollering, like they’ve come back from a hunt with a prize mastodon. The Eagles drone, fading in and out on the breeze, but he knows what they’re saying. What they’ve always been saying. You can check out any time you like. But Charlie can’t check out, and he can’t leave either. He steps through the woods, picking up sticks. He has an ear worm now. And mosquitoes. The bugs are coming for him, all at once. He grabs a stick that looks good and dry but when he picks it up it’s wet and slimy, falls apart in his hand. And there’s no way Maddie is just sitting here in the woods, hiding behind a rock or something. She’d be eaten alive out here by the mosquitoes. What fun is that?

Charlie steps out onto the road on the other side of the loop, with a pathetic handful of twigs. It’s quiet. Even the radio has stopped. And no voices calling out for Maddie or anything else. He just stands for a second listening to the quiet.

He looks to the left, to the right. Nobody. Their stuff is here, their tents and bikes and wet bathing suits on the line, but no people. Like the Rapture, isn’t that what happens, everyone vanishes, all the good people, leaving the sinners behind? Charlie is a sinner. It’s why he’s never been able to sleep. His guilty mind, his bad attitude, the way he judges and complains and eats all the graham crackers they were saving for s’mores. All he can hear now are the mosquitoes quietly buzzing, one near his ear, louder now, but his hands are full of twigs. He could drop them and swat but he can’t have both. Now there’s a crow flying over the place and cawing, looking down on them, or on Charlie, just Charlie, the only man left. Calling some kind of warning to the others—there’s one here, one left! It’ll just be about survival now. Charlie, alone on earth, sleeping, maybe at last he’ll be sleeping. He stands for a long time alone, an elongated minute, maybe two, his eyes burning and knees trembling and another crow crossing the sky. Nothing else. What have I done, oh what have I done to deserve this?

But here comes someone, around the bend, the guy with the tattoo and his little girls. There are still people here! Here they come, and the guy is carrying a small, limp body. It must be Maddie’s body, there’s the pink T-shirt, just like they said. A chill passes through him. Is this how it ends? Where are the authorities, where is her mother?

The guy nods at Charlie. “Kid fell asleep,” he says quietly. “In a tent with some new friends. But thanks for your help.”

The little girls look at him solemnly, one even puts a finger to her lips. Shushing him before he has a chance to speak.

He just stands as they walk past, Maddie’s head over the man’s shoulder, the other girls quiet, self-important, they’re the heroes today, they found her in a neighbor’s tent, sleeping. Oh, blessed sleep, why her and not me? Why never me?

Maddie opens her eyes then, looks right at him. She’s giving him a look, he swears it, a knowing look in those sleepy eyes, beneath those sweaty bangs. She winks. She winks at him! Like, joke’s on you, sucker. I can fall asleep in the middle of the day, in a stranger’s tent, in the heat, with people shouting all around me. I can sleep any time I want. She’s like a little angel, or maybe the devil, he can’t tell.

Charlie drops the pile of twigs next to the fire ring, sinks his whole weight into the camp chair. He feels dizzy now. He just wants his family to come back. He doesn’t care how noisy they are, how angry that he’s eaten the graham crackers and ruined the camping trip. He doesn’t want to be alone here anymore with these people, those crows, everyone taunting him.

A small part of him maybe hoped something bad would happen. Not that he really wanted a tragedy for those people, but then maybe Julie would’ve hurried back with the kids and they’d be so grateful for each other, so grateful they were alive, that nobody would care about another bad day at the lake, another ruined vacation. A crisis would put things in perspective. And then they would’ve just packed up and left before nightfall. Surely they would not have wanted to spend another night here if a little girl had gone missing, or had died somewhere in the woods, or drowned in the lake.

He hopes Elise and Evin are behaving themselves down there. Listening to Julie when she tells them to stay close to the paddle boat, not catching a fish hook in the eye or swimming into the blades of a motorboat. He hopes they come back soon, all of them safe and happy. He’ll get the fire going now, make it nice. The smoke will help with the bugs. It’s only two in the afternoon, but evening comes early in the woods, even in August, and soon enough he’ll be able to go to bed. Just a few more hours. He can take a few more hours of this. Julie and the kids will come back from the lake with their stories about whatever they did today, and everyone will forget the way he stomped off earlier, like a petulant three-year-old. He only wants them to be happy, with or without him, and then to come back and tell him all about it.

But maybe this is finally the end. Julie will just go through the motions with the hotdogs and marshmallows till they get home. Reason for divorce? The man hates camping. He wouldn’t blame her really. He doesn’t want to be stuck with that guy either.