The idea had been to have a celebration. I’ve been dieting all week for this, the mother had said. I could kill for a burger. The daughter had picked up the last of the groceries Friday after work: papery heads of garlic, woody stems of rosemary, a dry red, and the leg of lamb, wrapped in butcher paper and tied into a bulky oblong parcel with kitchen twine. The mother looked at the parcel, wrapped and still on her kitchen counter, like one might a live bomb.

“I went to the good butcher,” the daughter said. “The one on Highland.”

The mother, newly pale, nodded.

The celebration was for a new job the daughter did not want; she thought that perhaps throwing the celebration would make her want it. The mother had suggested the celebration but the daughter had suggested the lamb. It was spring. There would be peas, and mint.

“Did you get the mint?” The daughter asked.

The mother wrinkled her nose and winced: an apology.

“That’s fine.” She began smashing garlic cloves on a wood cutting board with the side of the chef’s knife she’d brought from home.

“I like them better plain. Can’t we have them plain?”

“Of course we can have them plain.” The daughter’s tongue pressed against the words like they were a jammed door. An old habit.

The mother began taking baking sheets and pots out of cupboards. “So. Aren’t you excited?”

They had not cooked together much. The daughter and her late grandmother, the mother’s mother, had. Once, when the daughter was in college, the grandmother told her, as they stood waiting over a bowl of bread dough, its mass stretching and bubbling, that she had once left her husband, for three hours, in the middle of the day. She had gotten 74 miles before she turned around, and dinner was not even late when he got home from work. The mother, then a child of seven, had been in school the whole time. When the grandmother told her granddaughter this, the odd precision of the mileage had started an inchoate sorrow blooming deep in the granddaughter’s gut. “You understand,” the grandmother said, and she had in fact understood, though she did not know why her grandmother was so confident that she would.

“I wouldn’t say excited,” the daughter said now. “I’m beginning to feel it’s a mistake.”

The mother wrinkled her nose again. “Here,” she said, placing another baking sheet on the counter for the potatoes. The daughter began peeling a price sticker from its surface.

“You’ll be excited once you get there,” the mother said. “You’re just on edge. Since the—” She was not groping for the word but holding space for it; the mother spoke about the incident this way, with a gestural silence. It made the daughter think of an empty table setting.

“Maybe,” the daughter said.

◆

When the oven was preheated, the daughter unwrapped the lamb parcel.

The mother had never made them lamb, had rarely even ordered it in a restaurant. “What do we do with it?” She was standing behind the daughter, looking over her shoulder.

The daughter explained that first they were going to cut small slits in the meat, then fill the slits with the smashed cloves of garlic. She handed the mother a paring knife. The mother was staring at the end of the leg, at the joint where it once connected to the hoof; she gazed at the cut, the milk-colored density of bone at its center, but said nothing.

“I had the nicest chicken breast the other night,” the mother was saying as the daughter made the slits. “Boneless, cajun seasoning. At Grimaldi’s. The four of us will have to go.”

The daughter glanced up from her work. “Mother.”

“When you’re ready.” And then, when water began to gather at the edges of the daughter’s eyes: “All right.”

◆

The word the daughter used for the incident: revelation.

◆

“I think this is going to be a great thing for you,” the mother said. This was one of her favorite words. She’s great, thank you for asking. We’re all great.

“It doesn’t feel right,” the daughter said. She was stripping rosemary stems of their leaves, her left ring finger stiff in its splint.

The mother blanched. “Is that blood?”

A small amount of blood was pooling at one of the slits in the lamb. It was seeping into a garlic clove, turning it pink and spongy. “It is an animal, Mother,” the daughter said.

The mother shook her head. “I don’t like that.” She always ordered meat well done. “Thank God there was no blood in that chicken breast, I’d have screamed. When was the last time you were at Grimaldi’s?”

The daughter began mincing the rosemary leaves, rocking the knife from tip to handle. “The rehearsal, but I really—”

“That’s what I thought,” the mother said. “See, I think the new job, a nice dinner, being back there—”

“I feel how I feel.”

“Well, of course,” the mother said. “But feelings change.”

The daughter paused, the knife in mid-rock. How did this prove both of their points?

“The job will make you a lot happier.” The mother began spraying the countertop with disinfectant, wiping around the cutting board and pile of potatoes and sliced lemons and the bowl for the minced rosemary leaves, giving everything a miasma of bleach and artificial lemon. “You’ll see.”

The daughter had been imagining, lately, the moment her grandmother drove away. Her child at school, her husband at work, her life ready to be locked in a drawer. She wished she could ask her grandmother if for her too it had bubbled up from some low and silent ferment. No horrible fight or shocking deceit. Just sunlight, so antiseptic and strong that it made shadow impossible.

◆

“You’re OK, right?” the mother had asked. It was two days after and they were at a diner by the hospital, voluntary check-ins being able to check out whenever they like. “I don’t need to worry about you?”

The daughter was drinking coffee and spinning the paper bracelet around her wrist. “I’m great,” she’d said.

“Leave it be now,” the mother had said, placing a hand over the daughter’s braceleted wrist.

When the mother asked how she could help, the daughter told her to mix two teaspoons of kosher salt into the rosemary leaves and then slice the bread, which the daughter had baked herself the night before.

“As long as I don’t have to touch the lamb,” the mother said.

“I’ll take care of it,” the daughter said.

She had expected this. During the daughter’s childhood they had not cooked at home much. The mother’s new energy for entertaining, the baking sheets with price stickers still attached, came with her third marriage. So did the house where they were cooking, large like the one the daughter and her husband had been planning to buy. The daughter suspected that the house was what the mother had meant when she’d said that feelings change.

◆

When the seven-year-old mother got home from school that day, something felt off, like turned milk. But everything, everyone, looked the same. She would take comfort in this for years, her house where everything looked the same. If she could still touch her dollhouse, still tug at the edge of her mother’s apron, how different could anything really be? Eventually, different became an illusion.

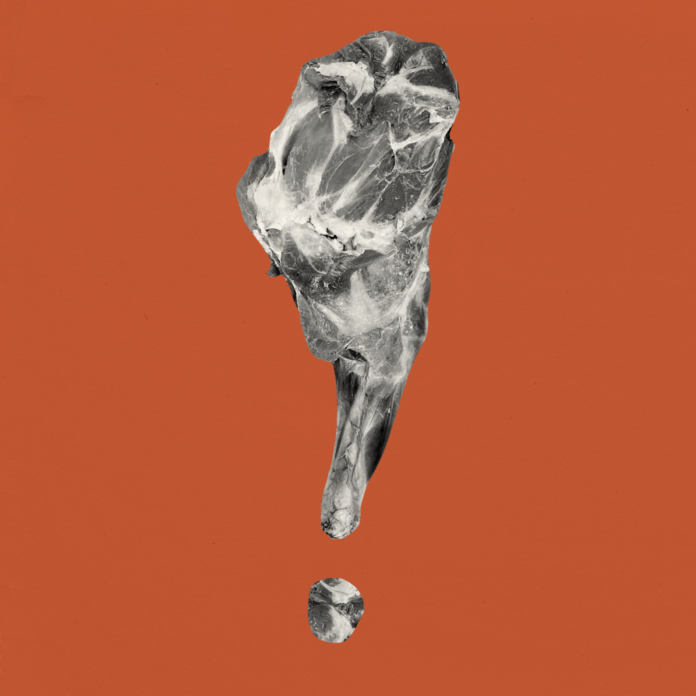

The daughter had stuffed the lamb with garlic cloves and rubbed the top of the meat with the rosemary and salt. “Now we do the same to the other side,” she said, and when she flipped the lamb over, there it was, pressed into the flesh: an eye.

The mother screamed. “Get it out get it out get it out!”

The daughter bent closer. The eye had the same milkiness as the bone, a cloudy swirl like white granite. The iris was a flat brown, mud beginning to harden. The daughter was bent over, head tilted; her nostrils filled with the raw sting of the garlic and the oily residue of the rosemary, plus some alive, metallic pungency from the meat. She would have expected a hollowness to the eye’s gaze, but instead it looked at her in a spectral way, from some distant place, and a current of electricity inside her began to crackle. She stared back hard but could not see the place where the eye was looking from, could not reach it as much as she wanted to, as much as it seemed to be showing her how to find it.

That day, the seven-year-old mother had gone straight to her room and started cleaning. She had lined up her family of dolls in a neat row where her bed met the wall. She had put away the previous day’s clothes, flung on a chair. She had re-made her bed, tighter and smoother than she had that morning.

The grandmother had kissed her daughter softly on the forehead. “That’s my good girl.” Then, a little bit later, the mother had approached the grandmother’s bedroom, with its silky folds of pink curtains and lingering scent of rose water, and found her standing too still before her vanity, eyes closed. It had taken the seven-year-old, paused in the doorway, a moment to understand the stillness: Her mother had been holding her breath.

The daughter picked up the eye and held it in her palm. It felt like nothing she’d ever touched, like a ripe cherry dipped in gelatin.

“Don’t touch it,” the mother said, aghast.

The daughter stroked it as if it were a pet, feeling its marshy surface acquiesce to the pad of her finger.

“You don’t know where it’s been.”

“It’s obvious where it’s been.” Holding the eye gave the daughter a calm she could not explain.

“I can’t watch this.”

The daughter laughed at this, a hard and spontaneous laugh that surprised and delighted her. She couldn’t stop laughing, in fact, even though the mother’s face contorted into more horrified expressions the longer the daughter went on. Finally, her laughter melted into giggling, then into a soft smile. Her blood flowed in sharp pulses. “All right,” the daughter said. “I’ll take care of it.” She bathed the eye in warm water and dried it with a paper towel. Then she wrapped her hands around it, lifted her hands to her sternum, and closed her eyes.

“What the hell are you doing now?” the mother said.

The daughter was silent for another moment. Then she wrapped the eye in the paper towel and put it in her pocket. “There,” she said. “It’s gone.”

“Thank God,” the mother said.

It was almost 6; people would be arriving soon. “Don’t tell them,” the mother said. She washed her hands even though she had not touched the eye, or the lamb. “I don’t know how I’m supposed to eat after that.”

“I’m starving,” the daughter said.

◆

As the daughter was pulling the lamb from the oven, she realized that she’d never had any intention of going to the new job. This gave her the same calm she’d felt while holding the eye, which was curious—for the second time, something momentous had arrived wrapped in stillness, not in the seismic anxiety that accompanied so many smaller events she experienced every day. The feeling jarred her back to the diner by the hospital. The melancholic clouds hanging in the sky, the fresh-rain smell of the parking lot; everything felt heavier but also scrubbed clean. That moment of the past felt more real than this moment of the present. The new job seemed now like something another person was doing, like a story she’d been told about someone almost like her.

She moved the lamb from the roasting pan to a serving platter, then carried the platter to the dining table. She began carving, making short slices down the leg. The mother got up and, under the auspices of serving potatoes, slid beside the daughter’s ear to whisper: “Are you sure it’s done? It’s pretty pink.”

The daughter looked at the sliced lamb, its center the color of bubble gum. “It’s perfect.”

The mother took only a small piece, from the very edge, brown all the way through. The daughter, though, ate and ate, taking a third and even a fourth helping of the lamb. The older adults around the table—relatives and family friends, mostly—smiled their approval, as if the daughter’s appetite was evidence of a problem solved.

“Your mother was just telling me about the new job,” a family friend said. “It sounds fantastic.”

The daughter smiled. “It does.” She popped another bite of lamb into her mouth.

“I’ll bet you’re excited,” said another.

“How could I not be?” the daughter said.

An aunt, watching the daughter chew her lamb, served herself another spoonful of peas. “Nothing better than fresh peas,” the aunt said. “That’s how you know it’s spring.”

The mother smiled. “They are delicious.”

“It’s the funniest thing,” the daughter said, loud enough to quiet the side conversations around the table. The mother’s eyes widened.

“Oh?” the aunt said.

“I was so excited to have peas with mint,” the daughter said. “But Mother forgot to buy the mint. Conveniently, I think.” She winked, giving the room permission to let out a giggle like a kettle whistling. The stress in the mother’s face deflated.

“You don’t need anything when they’re that fresh,” the aunt said.

“I agree,” the mother said, her tone taut.

“I would prefer the mint,” the daughter said. “But they are very tender.”

◆

After the party, the daughter and the mother were cleaning up the kitchen. Since taking the lamb from the oven, the daughter had felt a gentle floating that had made her feel bold, and a little bit drunk. She was about to ask the mother a question but the mother, placing slices of leftover bread in a zip-top bag, spoke first.

“This tasted familiar. Are you sure you didn’t buy this somewhere?”

The accusation, its oddity, sent an unease whistling through the daughter’s body, like the tender shock of an unbandaged wound exposed to air. “What? No, I made it.”

“I don’t believe you.”

The daughter felt something sweet begin to evaporate. Instinct told her to chase it, and this made the whistle louder. “There’s nothing to believe, Mother. I baked it.”

The mother picked up the bag, examining the slices from all angles before frowning and tossing the bag on the counter. “I don’t see the point, anyway. Just buy it.”

Without realizing it, the daughter had been backing up; she was against the counter now and still pushing, the lip of granite digging into her backside. “It’s—” Speaking felt unsafe, which felt ludicrous. “It’s meditative.”

The mother frowned again and turned her attention to the sink full of dishes.

This exchange threw the daughter from the question she had been waiting to ask, but the eye, still in her pocket, urged her on with its warmth. After a moment, she asked it. “You thought I was going to tell them, didn’t you?”

The mother was washing plates by hand instead of loading them into the dishwasher.

“Mother.”

Three scrubs of the sponge for every plate, one pass under the faucet, into a drying rack of gleaming porcelain. One after another after another.

The eye gave off heat like a burning coal now. The daughter had never forced her mother to answer for anything before. She asked again, louder: “Mother. Didn’t you?”

The mother stopped the water, and the abrupt absence of sound was louder than the running faucet had been. She ran her wet fingers through her hair, pulling it taut against her scalp and tying it into a stern ponytail before turning to face the daughter. “Didn’t I what?”

The daughter flexed her fingers out of the fists they had become, the sweat on her palms evaporating into cold. She thought again of the diner by the hospital. The fresh-rain smell. Scrubbed clean. She was in the passenger seat of her mother’s car; the doors were locked. The car was spotless, as the mother’s car always was, but it was a different kind of clean.

◆

The day the grandmother almost left had been so sunny. It was the sun that made her leave, and the sun that made her come back. The open-eyed possibility of it, and then the way it made everything appear brighter. It felt so true on her face, through the windshield, that she closed her eyes into it and sat in the driveway, her foot on the brake, the engine humming, waiting for the sensation to pass.