Three years after our son Mack disappeared, I found him on the back deck, sitting in the dark as if it belonged to him. During his absence, someone had taken the curl from his hair and the child from his face, but it was this other change that first caught my breath. Before he vanished, Mack had been terribly afraid of the night.

I stepped cautiously forward. Of course I wanted to run to him, to hold his body until I was certain he’d been absorbed back into our life, yet there was too much risk in this. When I say Mack disappeared, what I mean is that he left us. Any hardened movement chanced another departure. I paused midstride, deciding that words might be softer shepherds than my body, touching down on the redwood slats as if they might give way.

“You’re back,” I said.

“I’m here,” he corrected me, eyes fixed on the yard.

This time I toppled forward. The last time I’d heard him speak, his vocal folds were short and thin, producing a brassy register shared only by trumpets and geese. Now, a man was hiding in his throat.

“Oh, Mack. Please look at me.”

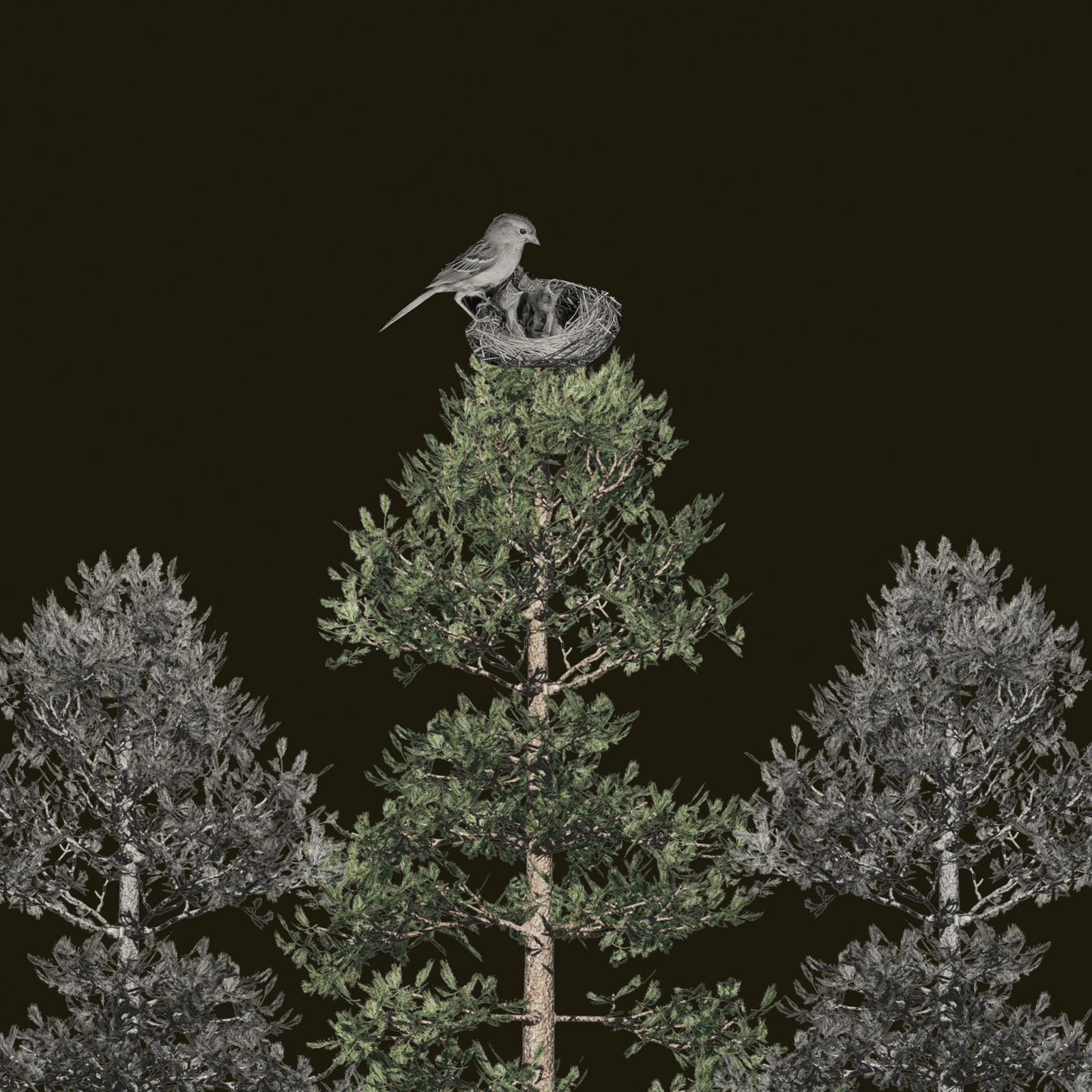

But he would not look at me, or at least not then. Our lawn fell away to a hillside heavy with sugar maples and holly, and then, of course, there was the pond. Regrettable things had happened down there, and I was sure the line of Mack’s gaze ended in that coalish water, that he was somehow able to see through the thickness of trees, night, and history separating that day from now.

“Can I make you some tortellini?” I asked. It was an appeal to the past Mack, the 11-year-old who would unfold the pasta until the wedge of cheese was dislodged from the inside, at which point he would rejoin the two in his mouth, fingers shiny with butter and spit.

“I’m not here for tortellini,” he said, finally turning toward me. His new face was so like his mother’s that a shock of jealousy ran through me, as if he’d hand-selected the DNA he wanted to display. “I’m here to perform an evaluative assessment of the household. The purpose of this assessment is to determine how suitable the space is for a child.”

It was clear he was paraphrasing some formal document, and when I noticed the clipboard in his lap, my first impulse was to tear it from his hands, break it over my knee, and throw the parts as far as they’d go. There was a time when I could rip book spines in half with relative ease, when the backyard was often strewn with objects I’d flung there—utensils and couch cushions, dishware and the fish-shaped landline. Lately I’d been working to dethrone my first impulses, having learned through online tutorials that anger is not a fated force to which we are doomed. I took pride when I asked, simply, “What’s that?”

Mack hugged the clipboard to his chest and stood. “That is for me.”

I could hear the wind before it hit us—snaking through the leaves, practicing its cold for the coming winter. When it found our bodies, Mack’s hair fell over his face, and for a wonderful moment he looked vulnerable, tossed back to the days when he was small and often flinching. I took the chance to remind myself that he was only fourteen now, that the yard and deck and house were mine—that, above all, I was the parent and he was the child. Taken together, these facts made a compelling argument for my authority.

“Let’s go inside,” I said. “Your mother will be excited to see you.”

Mack’s expression moved around before settling into a smirk. “She shouldn’t be,” he said, passing by and pulling the door open. Even I was surprised by the ease with which power was reclaimed. Another impulse began to flex inside of me. I fought this one off, too. My son was back. He was here.

◆

In the kitchen, Mack declined my second offer of food. “Where’s Mom?” he asked.

“Downstairs.”

“Downstairs. Why?”

I wanted to lie—she was changing the laundry, practicing kickboxing, resetting the breaker—but the words held at the bottom of my throat.

“She’s been living down there,” I said, transferring my weight to my palms hugging the porcelain rim of the sink.

Mack raised his eyebrows and jotted this down. “For how long?”

“Since you left.” I shrugged. “More or less.”

More or less included Laurie’s migratory period, which began three days after Mack said goodbye and continued for a month after. She slept in the office first, the guest room second, and Mack’s room third. His silhouette was still on the sheets, a sweat shape that wouldn’t wash out, and for five nights she pressed her body to the stain, imagining, I assumed, that it somehow contained him. Of course, it didn’t. On the sixth night she moved again, sleeping for a while on the living room couch before planting herself in the basement by the furnace.

I left Mack scribbling his pen in the kitchen and called down to Laurie, who was in the midst of her nightly meditation. Every few months she tried new ways to find happiness, and I’d decipher her means through some oblique code, given how little we spoke, and even then about subjects far enough away to become abstract: the politician who believed in past lives, the dolphin beached at a birthday party. Her meditation had been easy to deduce: each night, the smell of incense or burnt sage lifted through the vents, and each morning an aphorism was written on the refrigerator’s white board. Today’s read: Be where you are; otherwise you will miss your life.

Laurie did not respond to my shouts until I mentioned Mack. Then I heard her scuffle up from the floor, bare feet slapping on the way to the stairs. I was hardly back to the kitchen when she came running in from behind, not stopping until her arms were flung around him.

“Mackie,” she cried into his hair. “You’ve come back for us.”

I waited for him to correct her, imagining what face Laurie would make when he pushed her off and told her what he’d told me. Mack stayed quiet through the tears, though, even lifting his hand to Laurie’s head and cradling it beneath the ponytail. Envy began to hurt me again. Before he left, Mack and Laurie occasionally snuck off to the gas station for M&Ms, or to the movies without me. When it rained, they sang a jingle I’d never heard, refusing to tell me the source and laughing if I asked. Eventually I punched one of the ceramic pots we had on the kitchen sill, its dirt spilling around my wrist. Then Laurie told me, but the singing stopped.

I moved toward them, thinking I should separate their bodies before Mack got fooled into forgetting all of the ways in which Laurie had disappointed him. He’d enumerated many of her worst traits in his declaration of departure, which he’d read to us before leaving. I wanted to remind him of those now: how she left for days at a time, driving up and down the coast with her phone turned off; how she slept on the floor of his room when she drank too much, once wetting herself in the exact center of his carpet. There was more, surely, that I was forgetting now. And for myself—of course. That didn’t matter. Mack never failed to recall my worst days.

I was almost to Laurie’s back. Pulling them apart would be as easy as twisting a chicken leg from its socket. Only when I started to lift my arms did I realize that it was my own reticence that kept me from Mack out on the deck. If I’d gone to him, maybe his hand would have held my head, too. My body’s course changed direction, folding itself around them like a wing over eggs. I could feel the distances dissolving between us, cruelties bowing their heads and walking away. Briefly we were singular, an untranslatable term, until Mack shrugged us off.

“Should I make tortellini?” Laurie asked, wiping at her cheeks. “Or sweet potatoes? Or cobbler?”

Mack told her about the evaluation. I watched as her face fell in at its center, a sinkhole opening somewhere behind her nasal bridge.

“Okay,” she said, taking a step backward. “I’ll just go make up your bed, then.”

“No thanks.” Mack straightened his shoulders. “I’ll be sleeping in the yard.”

“The yard?”

Mack nodded. “I’m a survivalist now. I know how to make it on my own.”

Neither of us knew what to say to this. Mack suggested postponing the evaluation for morning and walked out the back door before we could respond. After he was gone, Laurie and I stood together for longer than we had in months, both waiting for the systems we’d built in Mack’s absence to reengage. Soon she would back to her practice, seeking nirvana. Soon I would be back at my desktop, watching a testimonial on subduing one’s worst self, or maybe a live concert that had nothing to do with improvement. Laurie peeled a clementine but did not eat it; I wiped crumbs from the counter, listening for atmospheric disturbances from the outside world, any sonic shape that might indicate Mack.

“Did you see his hands?” Laurie eventually asked.

“His hands?”

She collected the clementine parts. “Yes,” she said, dropping them into the trash. “They were awful.” She shook her head and retreated to the basement, muttering about something she’d left burning. I went to the window to look for Mack. Night veiled everything beyond the braided mat we kicked our feet on.

◆

The next morning, I discovered Mack had erected a blue tent in the middle of the yard, its nylon stretched tight enough to reveal the fiberglass skeleton beneath. I dressed and made my way outside, noticing how the fabric was studded with dew flickering like jewels in the morning light.

Mack unzipped the entrance before I could knock.

“Morning,” he said, tugging his shoes on.

“I thought you’d be in one of those shelters made of sticks and leaves,” I said. “Does a tent even count as a survival structure?”

Mack paused in his lacing. Before he met my eyes, I wondered if my wolf had successfully blown down his walls. I imagined him shrinking to his last size, the hair sucking back into his head, bones made thin again. A body like that was defined by its fear. I longed for him to cower. When he did look at me, it was clear this new Mack would not be so easily beat.

“Any structure can be a survival structure,” he said, rising from the tent and zipping it closed. “Where you stay depends on what you have. Sometimes that means a round lodge. Sometimes that means a snow cave.” He pointed behind him. “For now, I have a tent.”

A few paces from the tent’s eastern side, Mack had set up a water-trapping apparatus: six slim branches pushed into the dirt, their extraneous twigs snapped off and their postures stiff enough to resemble bamboo. They stood in close pairs, the branches held apart by a half-inch gap that widened slightly on the way up, and at the top of each set, a condom was placed, its body hanging loose between the sticks and its mouth open to the sky. The branch tips held the rubber ring in a taut oval—tight enough not to fall, but not so tight as to prevent water.

“Not as much as I’d hoped,” Mack said, combining the accumulated precipitation into a single condom, which he then tied off and attached to his belt. “But good enough for now.”

I’d struggled to keep stride with each of his changes, but this stretched beyond all the others. As he handled the latex sheaths, his demeanor was one of unabashed ease, as though he’d grown familiar enough with sex for it to lose all eminence—of shame, intrigue, or delight.

Mack noticed me staring at his waist. “Did you know that condoms are great tools for survival? I can get them to do almost anything I want.” He slapped at the one on his belt, making it jiggle. “Besides the obvious function, I’ve used condoms for knots, slingshots, wound treatment, and storage. It’s amazing what you figure out when left to your own devices.”

Who was this boaster, and where had he abandoned my child? When I opened my mouth, I did not expect to beg.

“We have a house, Mack,” I said. “We have a house and water and food that can be made in an actual kitchen. We have a bathroom. We have a laundry room. Come inside. I know it hasn’t always been good, but you’ll see it’s better.”

Mack seemed unmoved until this final entreaty, at which point he closed his eyes. I wondered what was happening beneath his lids, willing certain revelations of the family—that blood bends but does not break, that the best treatment for a fissured life is a forgiving life. In the past, he’d understood these things intuitively, crawling into our laps whenever our fights had exhausted their energies, rubbing his hands on our swollen throats.

His eyes reopened. “We should get started,” he said. “I know you both have work on Monday, and I’d like to be done by then.”

I swallowed my disappointment. “What happens after Monday?”

“That’s for Tuesday to figure out.”

◆

Laurie and I sat close enough for the scent of sandalwood smoke to surround us both. I found that the incense affected me differently with each breath, pushing me toward calm and nausea in equal measure. How strange to be close enough to touch her, to feel the old muscles sputter on, woken by memory. The thought of putting my hand on her thigh was a mystifying one. The possibility of her head on my shoulder made me dizzy. I couldn’t tell if I missed Laurie or if I missed human heat. Across from the sofa, Mack was poised in the wingback chair, his general dishevelment emphasized by the floral fabric.

“The bulk of this evaluation happens in three parts: the past, the present, and the future. We suggest moving in that order but are flexible to the needs of the parents.” Mack looked up from the clipboard with a small, professional smile, then looked down again. “Do either of you have a preference for where we start?”

Laurie leaned forward, losing her head to a beam of sunlight before pulling it back again. She began explaining the Buddhist perspectives on these temporal distinctions, and I let my mind wander away from her voice. The last time we had all been together in this room was the day Mack read his declaration. Before that were dozens of memories I wanted to resurrect and let run through the room now. It seemed unfair that one unfortunate day might eclipse all the rest—those nights when we’d order fried rice, lo mein, and orange chicken, combine the three in our largest mixing bowl to pass around while watching TV; that day Mack sang the national anthem in the voice of Kermit the Frog, pausing between verses to calm his laughter. I would drink these memories if I could.

The room returned to me as Laurie was finishing. “For these reasons,” she said, “I would like to begin and remain in the present.”

Mack wrote this down. “We will be covering all three. Starting with the present is certainly an option.” He nodded at me. “Do you have a preference?”

My preference was for Mack to have never left, for him to be sitting on my left and saying the birthmark on my thigh looked like a rabbit’s foot, that all of the United States could fit into the northwestern portion of Africa. Laurie squeezed a cushion beside me, and I remembered what she’d said about his hands. Propped in his lap, they were wide and calloused, the hair on the fingers darkened. And they were awful, but only because we’d missed them getting there. I could have loved those hands, I thought, if only I’d watched them lengthen, harden, grow. I could have loved that voice, too.

“Where did you go, Mack?” I asked, the question having burned for too long. “I want to know where you’ve been. I don’t care where we start.”

Mack nodded, setting the clipboard on the arm of the chair. “I wondered when you were going to ask,” he said, leaning back until his spine was flush with the stuffing. “I’m not able to tell you everything, but I can tell you enough. Capisce?”

I was surprised by the ease of this response, and more surprised to hear him use a word from his childhood. Capisce. He’d learned and loved it during fourth grade, chanting it like a hymn as he spun his way through the house. I wanted to hear him say it again, to hear him say it on repeat, but worried the offer would expire if given the chance.

“Yes,” I said. “Capisce.”

◆

Mack discovered the group online. What was it called? He couldn’t say. Where were they based? A motel in the desert. How many people were involved? Enough to fill the rooms.

They sent a driver to the house after Mack had put out a distress signal. A distress signal? An email. How long was the drive? Long. How many were in the car? Just the driver and Mack. Was the driver an adult? Mack laughed. No one in the group was an adult.

The motel had been vacant for some time. Though Mack’s room was on the second floor, a thin layer of sand still covered everything inside. In the bathroom, he found a tumbleweed that had somehow blown all the way into the shower. Was he scared? Of the tumbleweed? Of the place. He was never scared of the place.

There were several goals for the members, but autonomy was high among them. To this end, each person was required to become an expert on something that would help foster independence for them all: taxes, consuming wild berries, driving, fire-starting, renter’s rights, judo. The group would gather for lectures, and if someone was leaving, they had to pass on their knowledge to someone else.

What had Mack become an expert in? Animal tracking. He could decipher large, medium, small, and ghost scale signs that told him what he needed to know about the wildlife around him. Ghost scale signs? Signs that are temporary, given the interface they’re on. Meaning? Tracks through dew will be gone by the afternoon. I thought of the dew on his tent, and how it glistened. Mack’s teeth glistened, too, as he spoke about animals that stalk, lope, and gallop; scat that tells you something and scat that tells you nothing; the range of chew marks that can be found on leaves and bark, and what those marks might mean for your own life.

Was someone in charge? That was against their value system. Was there any prerequisite for admission? No. Had anyone ever been kicked out? Yes. Why? They called their parents. What was wrong with that? The parents found the location, thus threatening the group’s primary function of sanctuary. The word, with all it suggested, caused Laurie and me to both shrink in shame. We were even closer than before, yet still not touching, her wrist tiny beside mine.

Mack brought our attention back to the clipboard. The evaluation had been written by a member for those who wanted to assess their former households. A kid wrote that? Mack nodded. I thought of my earlier fear and felt foolish. Even in outline, Mack’s time away became less formidable, a contoured thing that could be dismantled. My calves relaxed. Past, present, or future? Mack asked again.

Wherever you want to go, I replied.

◆

We began with the present.

“Does this mean the here and now,” Laurie asked, “or the time since you’ve been gone?”

Mack thought about this, the slant of sunlight now at his knees. “Either works,” he said. “I need to know where you are today. If that means knowing what’s happened in the last few years, that’s okay, too.”

It occurred to me that this was a softball question for Laurie. She knew it, too, smiling as she set her feet and swung.

“When you left, Mackie, I really took your words to heart. I put my head down and said, Listen here, missy: you command your own ship, and you’ve got to set sail for better waters. I wanted to find something that was just mine, so I started going through a list I made: scuba at the pool, banjo lessons, billiards.” She paused, laughing at her own antics. “I even tried squaredancing. Can you imagine it? Me, swinging around with strangers?”

Mack was writing with intense focus, but his mouth lifted with this detail. Even I was reluctantly pulled in by the determination of her story, as if forgetting I’d lived two floors above it. Until now, I’d been more attuned to the frequency with which she dropped her hobbies, to the lulls that gestured toward Laurie’s flimsy resolve. Told in sequence, all of her starts and restarts amounted to something triumphant.

“I’ve really found my place with meditation,” she concluded. “I’m sober, not that heap of misery you left behind. If old Laurie raises her head, I just say, Goodbye, girlfriend, and bingo: she’s gone.”

Old Laurie. I asked myself if I missed her. Sometimes, yes. Old Laurie was the one I fought with, but also the one I believed in. When we met, our failed first marriages still clung to our skin like sunburns; in bed, we talked about the sting and helped peel off the dead layers, confusing this sharing with romance. We’d both been cheated on, gone back, and been cheated on again. She recalled for me the toxic scent of latex. I recalled for her the pair of jeans I’d found in the hamper, bountifully stained. Each detail bolstered our resolve: we were loyalists, perfectly matched for the uncaring world. After marrying a year later, I remember thinking I’d finally obstructed my past, that Laurie was the barricade who would keep my abandonment away. With Mack, we safeguarded that belief even further. Safety in numbers, I thought the day he was born.

Mack turned the page. “I’m ready when you are.”

“Sorry?”

He glanced up. “Ready for your present.”

I did not look at Laurie’s face but imagined it glowing with self-satisfaction. In Mack’s absence, I’d gone to work at the insurance firm. I’d come home. I’d made myself tuna sandwiches and layered them with potato chips. On weekends, I played catch with my friend, Terrance, ate microwaveable meals for dinner, showered at night. If I’d gotten better at anything, it was masturbating; the trick, of course, was to involve more parts of yourself. New Laurie moved by like a wraith, Mack’s vacancy settling like rust while my existence felt cool and perfunctory without them, a stack of routines carried out in solitude. Only sometimes did my resolve waver, when I would look at Laurie drinking a green smoothie and want to knock the glass away, her insistent transcendence along with it. Or when I’d go for long runs in the forest and find myself stopping at some old tree, tearing at its bark and branches until my hands bled. But those were outsider days in an otherwise quiet mode of being, quickly amended by watching others talk through their darkness. In terms of betterment, it all sounded negligible, even if you factored in the store of videos I’d watched—and those, I admit, had petered off over the last few months. I did wish Mack could see me typing. That was when my fingers were at their most tender.

“I’ve mostly been working,” I said. “I’m up for a promotion soon.”

Mack nodded, not writing this down.

“I don’t really know what to say,” I said. “You left. I kept living. I don’t think that’s such a terrible thing.”

“No one said it was.” Mack’s expression had the calm of a puddle. In the old days, it would fold any time I raised my voice or made a quick gesture. I had the urge to shout now, wanting to see if I could force the old twitch.

“Things really are better,” I said instead. “Your mom is happier. I’ve been working on my anger with these amazing videos. It’s much better than it was.”

Mack caught the pen beneath his palm. The sun was right behind him now, its light refracted in an empty glass vase. “How have you worked on your anger?”

“What?”

“Your anger. You said you’ve been working on it with videos. What does that mean?”

Somehow his face was even more still, though his speech had a new slant, one that he must have adopted from Laurie. There was such disdain in that tone, such disappointment, and it rubbed over me like sandpaper. Again I wanted to scream, to spit, to turn the table over onto him and press down until he pleaded to be let up. I forced the anger away, feeling it pool and ache within me. This I’d learned from one man’s testimonial: relocate anger when you feel it beginning to rise; by siphoning it, you remember that you are in control.

“I’ve watched hundreds. Thousands, maybe. My temper no longer commands me,” I said. “I am the master of my own ship. Anger is a wayward dog in an otherwise docile pack. I know how to hold it back.” I tried to smile yet had no sense of what shape my face made. I was pulling from the videos I’d watched, blurring platitudes, while the anger throbbed against my ribs. Their words—those of my comrades in rage—did not seem to be helping. This I should have learned from another man’s testimonial: you must build the right cage for your own beast. I hadn’t done that because the anger had seemed responsive to others’ methodologies. Now I worried its docility had only to do with being unprovoked.

“Can you remember the last time we fought, Laurie?” I asked.

Laurie shook her head. “I can’t remember, no.”

“See? It’s better, Mack. We’ve been working in our own ways to make it better.”

Mack rolled his eyes. “You live on separate floors,” he said, looking first at Laurie and then at me. “I’m not sure why you’re still together at all.”

Laurie leaned forward. “It’s you, Mackie,” she said, offering the same line we’d always given him. “We’re together for you.”

I nodded, afraid of what might rise if I spoke again. Laurie’s entreaty sounded much better than the truth—that for many years, our affection was fed by a loop of fighting, blaming the fighting on our former partners, then offering ourselves again as bandages for the bleeding, those shapes we’d first fallen for; that by the time this cycle sputtered, which happened around Mack’s ninth birthday, we’d held ourselves together in this way for so long that our bodies had grafted; that now, a separation seemed fatal, as it would require a proper tearing.

Mack stood from the chair. “It’s not me,” he said. For the first time since his arrival I thought he might cry. “If it were me, you’d have left when I did.” He shook his jowls like a wet dog.

Laurie reached her hand out to him. He stepped backward.

“I need a break,” he said. “I need to be somewhere else for a while.” He turned and left the house.

◆

I sat beside Laurie, turning over Mack’s final claim like a stone. If it were me, you’d have left when I did. I knew he meant Laurie yet tried to configure situations in which he was addressing me, or both of us. Neither of us really deserved to leave. We were both the trapper and the trapped, and Laurie’s litany of misdeeds had been nearly as long as mine when Mack had read them to us. True, she’d never chased him through the house or broken a hand on the garage door, but she had left him at a gas station and forgotten to feed him when I was out of town one weekend. He’d told us these things. I remembered them.

At the other end of the couch, Laurie was quiet. Her silence came in two primary modes: when there were no words left, and when there were too many. For the last three years, she’d been silenced by wordlessness. We both had, for there was nothing to say in the midst of our punishment. Currently I could tell it was the latter case, that she was holding a bundle in her mouth and waiting until it congealed into something dense enough to cause damage.

“He’s right,” she eventually said. “I should have left when he did.”

“You should have left?” I laughed. “He ran away from both of us, Laurie. Remember?”

That day was always a blink away, flashing before me now. Mack’s declaration had rendered both Laurie and I motionless. For several minutes we stayed frozen, the garish gold of twilight illuminating the walls around us. Then Laurie shrieked, prompting me to run outside, where I circled our neighborhood first by foot and then by car for two hours, finding nothing.

She hummed. “Okay, sure. Whatever helps that head rest easy.”

This was Old Laurie speaking—the speech flayed like a fish, its remainder sharp and bony—and her voice scratched against my clotted anger before puncturing it completely. I felt the heat as it spread through me, reaching my hands at the same as my feet. “You’re a drunk bitch,” I said, the words feeling luxurious on my tongue. “Mack doesn’t trust you.”

Laurie must have let her anger in, too, for the blood vessels in her face and neck dilated all at once. “Mack doesn’t trust me? He doesn’t love you. Do you know what he was like when you weren’t home? You could have drowned that day and he would have moved on in no time.”

“That’s not true,” I said. I could hear the doubt in my voice. It was the problem then and the problem now: that no matter how I worked to deny the thought, I could envision Mack and Laurie’s life without me, easily. Sometimes it was miserable. More often it was better.

On the day of the pond incident, they were huddled together in the kitchen, Mack’s knees trembling like reeds in the wind. It was one of the first times he had ever intervened during a fight, rushing out of his room after I’d flipped a chair and standing before Laurie with arms spread. “Stop,” he’d said, voice cracking. “Leave us alone.”

His barricade was a breakable one, yet my anger, which was adapting its behaviors every day, forever finding new ways to surprise all three of us, pointed me toward other means of hurt. “If you want me gone,” I said, “I’ll go.”

I watched their faces to see if this threat moved them. No, I wanted them to say. Of course we don’t want you gone. Seeing that they were unyielding—I’d said similar things before, never once following through—I pushed further. “Or how about this? How about I take myself out completely. I’ll kill myself.”

Mack’s face twisted and I knew I’d caught traction. Exhilarated, I fled the kitchen and ran outside, my frenzy fueled by Mack chasing behind me, shouting for me to stop. I made my way down the hill and didn’t halt until I’d plunged into the pond. The cold stillness enveloped me, delivering me briefly to another world, and then Mack was at my legs, trying to drag me toward shore. I remained facedown, resisting his efforts. I didn’t want to die, but I wanted him to believe it. Even through the water, I could hear the desperation of his screams. He was realizing how much he loved me, I thought. It was a beautiful bellow.

I tried explaining all of this to them that night, and again when Mack read us his declaration of departure. “It’s more than just the pond,” Mack had said, eyes dulled beyond recognition. “It’s my whole life.” And then he was gone.

Back in the living room, Laurie continued to berate me. It didn’t matter that she may have been right about Mack’s life without me. I couldn’t raise the white flag. I reached forward and grabbed a coffee mug from the table. My anger compelled me to throw it across the room, but it did not work alone. The truth about first impulses is they are still textured by the other faculties, even if they appear to be one dimensional. That’s my testimonial. And so I threw the mug with equal shares of anger and sadness, though one runs hot and the other cold. They both wanted the same thing. They both wanted to imagine that change could happen in something small enough to hold.

Like always, the fiction of this belief became apparent when it was too late: the porcelain broke cleanly against the wall before assembling in a sloppy mosaic on the floor. Mack witnessed the whole thing happen from the porch. When I noticed him, I wanted to cry out at the injustice of him seeing only this. How often had it gone exactly this way?

Mack stood at the door and shook his head. After a moment, he said, “Don’t follow me,” and turned back toward his tent.

“Congratulations,” Laurie said. “You did it again.”

◆

The couch held me like a tomb, slowing my breathing and stilling my limbs. I’d only felt immobilized in this way when Mack first left. Both times, it seemed possible that I might stay down forever. I finally stood when I heard a neighbor’s car door close, reminding me there was a world outside of this one, that Mack could easily leave ours for theirs.

I positioned myself in my bedroom window, watching the afternoon shade advance toward his tent from the yard’s western edge. I worried that the shadow would remind him time was passing once it reached him, motivating him to pack up while daylight still held stake in the sky. But then it did come, and nothing changed. This was the hour when Mack would normally come running in. The Old Mack. The Frightened Mack. I missed him.

It only occurred to me that he might not be in the tent when full night fell. Had I seen him go inside? Could he have slipped out when I was going up the stairs? I stood quickly, my head wobbly with blood rush as I made my way downstairs.

No lights were on in the living room, the darkness made wooly with the smell of Laurie’s incense. I imagined her in the basement, sitting calmly as I crawled through the dark, her thoughts evaporating while mine gained weight and velocity. Perhaps she was better than me, or closer to better. Perhaps Mack had come back for her alone. But then I was the one here now, the one out to save him, and didn’t that mean something?

Outside, the October air chilled my lungs. Each possible decision clarified itself at once—to crash down on Mack’s tent, to tear through its side and drag him into the house, to call his name softly from a distance—and I lurched forward, waiting for one to win over the others. I was almost to the tent’s door when I heard his voice inside, speaking quietly into a phone or recorder. I stopped, wondering if I should listen, if I might glean insight into what I could do today, or tomorrow, to make him believe I wanted him home more than I wanted anything. My body told me to leave him be. I walked barefoot beyond the boundary of the lawn.

I winced with every stride, surprised by the sensitivity with which I met each stone, stick, and bramble. After stepping in a mound of soft earth, I realized I was leaving footprints behind. Mack could track me here, reading the dirt until he was right against my ankles. I savored the thought, pushing my feet down harder and visualizing all of the things he might find in a father scale sign: proof of harmlessness (the father approached the tent then left it); evidence of change (the father’s trail leads back to the pond but does not end inside of it); and understanding that behind each step came a long history of love trying hard to disentangle itself from fury.

At the shoreline, the pond bit at my toes. When he was young, Mack had delighted in the way a glass of the water was clear, despite the pond itself being black. For an afternoon, he filled cup after cup, pouring each into a shallow ditch he’d dug and believing, truly, that his new pond would be different. I’d found the endeavor painful in its futility.

A branch broke on the far bank, its snap clean and deliberate. I scanned the perimeter for him, but night lay heavy in the trees. If Mack had come for me, as I hoped, I would have to wait for morning in order to see.