This one woman, Rebecca, on this one July evening, did something she never did before. She fell asleep on her sofa, with a lamp on. The day had been long, and her last unspooling thought was simply how happy she was to have made it this far. A smile of fresh air cradled her, and she slept for her favorite amount of time: eleven hours.

When she woke up it was with a jump, moon-eyed, choking on the thick pulse in her throat, hoping she had imagined the knocks at her door. A woman she didn’t recognize, with pitch black hair and a pitch blacker jacket, stared back at her through the peephole. Rebecca was relieved to see a woman. She opened the door.

“I’m very sorry,” the murderer said. And she knocked Rebecca out cold.

◆

Some minutes later, the murderer explained everything. She was here to kill Rebecca. Hundreds before, as hundreds after, had faced the same situation: these are your final hours. There is no escape. When Rebecca cried, the murderer offered a script of pity. When she protested, as they all do, the murderer pulled from her bag a Mylar pouch of blood.

“Look,” she said, offering the pouch. “Not anyone can just have a bag of someone’s blood. But I have a bunch. It’s the blood of other assignments. I will answer everything. I will prove anything. But I will not let you live much longer.” She dropped the bag on Rebecca’s rug, where it burst. “You won’t need to worry about the mess.”

“Are you a hitman?”

“No.”

“Can we make a deal?”

“No.”

“Please,” Rebecca said, “what can I do?”

“Nothing.”

And after crying at the murderer’s feet, with her robe’s eleven-hour wrinkles already fading, Rebecca understood. She, like everyone, could not save herself.

The murderer helped Rebecca stand and guided her trembling body into the palm print armchair. “Is there anything you want to say or do before you stop being alive?”

Rebecca raced across a world of desperate ideas. None came, until she looked into the murderer’s gray eyes. “Well,” she swallowed, “is there anything you want to do?”

Which caught the murderer off guard.

“Oh,” she looked away out the window, “I mean I guess, like.”

Rebecca braced still for death.

“How long have you lived here?”

“My life? Thirty-two years, on, on Earth,” Rebecca whispered to her angel of death.

“No, like,” the murderer laughed, “I just mean New York City.”

Rebecca obviously couldn’t laugh back. “Fourteen years,” she croaked.

The murderer said, “Nice.” Then she hummed for a second. “I’ve never been to New York like, ever. And my flight’s not until tomorrow morning.”

“I can show you around?”

“If you don’t mind?”

“I don’t.”

Then, almost like a trance, “There are three things,” the murderer said. “I want to see Queens. I want to watch a baseball game. And I want to ride the Cyclone at Coney Island, before I take your life.”

“Perfect,” Rebecca said. She felt for half a moment the purity of merriment.

◆

So our victim planned her plan. It was a favorite itinerary, simple but lingering, and Rebecca’s many prior runs had a perfect record for being at least impressive. She called it Queens Day.

Two trains later, there they were in Corona Park. A jittery Rebecca pointed to the New York State Pavilion. “That’s the New York State Pavilion.”

The murderer shielded her eyes to see. The day was warm but she didn’t seem it. “Okay.”

“They built it for the World’s Fair in the sixties, but now it’s falling apart.”

“Can you go in it?”

“I don’t think so,” Rebecca said. She realized the walk over could buy her an extra thirty, or even forty minutes of life, so she burst out, “but we could try anyway!”

The murderer looked away and said, “No that’s okay. I believe you.”

Rebecca kept her tears out of reach.

A segment of leashed summer children snaked off course in an arc around the duo. An extended route to the playground waiting for them. She wondered if it was some sacred protection that steered them from the murderer, and imagined how they each might die. Her face scrunched into concentration.

“The architect’s name was Lev Zetlin, which I only remember because guess what band played the pavilion right after it opened.”

“Who?” asked the murderer.

“Led Zeppelin.”

The murderer made no acknowledgment of Rebecca’s unbelievable fact. “What other trivia do you know?”

Trivia, Rebecca thought. The question felt like a gun to her head. “Well the towers were in Men in Black, but mostly everyone knows that.”

“I haven’t seen it.”

“How have you not seen Men in Black?”

“But I did get scheduled for one of the cast members next week.”

“To kill? Who? Is it Will Smith?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Is it Tommy Lee Jones?” Rebecca felt reassured by the kinship of death with Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones.

“I said I don’t remember.”

“You said you would answer everything honestly.”

“And I honestly don’t remember.”

The silence was tense and forever. The murderer took a picture of the Unisphere.

“You were assigned me weeks ago?”

“Yes. Usually two or three weeks, depending on how quick I am.”

“What did you think when you saw my name?”

“Nothing.”

“No like, I know you probably didn’t think anything special. But even just, literally, what went through your head?”

“Really. Nothing.”

Another awful forever went by.

◆

Rebecca took the murderer into the Queens Museum. She took their time in the watershed exhibit’s tall room. She noticed the murderer ignoring the descriptions in the Never Built New York exhibit, and gave long explanations and opinions for each project. There was time to buy, but the murderer seemed to be only half-thinking about the assignment.

“I like how much you know,” the murderer said, “how you explain things. You love living here.”

“I do,” Rebecca said. “I love living.”

“Everyone does.”

“What if I killed you?”

A pair of giggles bounced along the polished concrete. They snapped to look for the eavesdropping couple, before huddling.

The murderer whispered, “Another would cover my assignment. But you would have tried in your apartment, no?”

“I guess.”

The murderer spoke hauntingly, “You wouldn’t be able to.”

◆

Rebecca led the murderer into the highlight of the museum, the Panorama. A one-to-one-thousand scale model of all five boroughs. Worth seeing if you haven’t. The murderer, with her life of who knew how many horrifying horrors, was stunned, and the two of them clung to the railing of the dim walkway encircling the model. Rebecca pointed to where they were.

“See the park outside? You can trace our path back to my apartment. There. That street is the border of Brooklyn.”

The murderer leaned closer to Rebecca’s perspective, to her face. “It’s all so huge.”

“Right?” Cheeks inches apart. “Brooklyn alone is bigger than Chicago. Oh—!” Rebecca leaned to point at what the murderer did not recognize as Bay Ridge. “That row of yellow? See? That strip of yellow buildings? Oh, I might get dizzy. That was my first apartment!”

With Rebecca’s reach, the murderer looked not at the yellow brick rowhouses, but down at Rebecca’s hand, touching hers on the railing.

“You’re excited,” the murderer said to the hand.

Rebecca inched away.

“It’s cute,” the murderer told her. “Sometimes people try to have sex with me before they die.”

“You do have an Elvira thing going on,” Rebecca eyed the murderer’s sliver of bare skin across her hips.

“You think so?”

“Nevermind,” Rebecca said, sensing punishment.

“I did it once, when I learned not to do it again.”

“There’s a scene in When Harry Met Sally where they go to this exhibit.”

“I haven’t seen it.”

“Now you sound like a murderer.”

An old leathering man stopped behind them and tapped Rebecca on the arm. “Excuse me, but there isn’t a scene like that in the movie.”

◆

Rebecca bribed the teenager staffing the next step of her Queens Day: mini golf. For five hundred secret dollars, she received the promise that no one could play a round behind her and her happy murderer. She would not be rushed closer to the end.

They ate hot dogs from the concession stand, and carried cheap beers as they took turns putting mostly in silence. Rebecca chained nervous gulps one, two, three, four, buzzed before the third hole. The unbearable quiet finally popped.

“Are you even having fun? Can you say anything?”

Even the murderer, in her years of collecting death, laughed at the request. “Relax.” She took some grinning gulps of her own. “If you want it like that, then okay.”

Rebecca felt that grin extend her life.

By the seventh hole, they were both feeling light and burpy from the beers. The murderer, peering from ten yards down and squatting by the hole, called out teasing, “It’s like you’ve never held a club before.”

“What do you mean?”

The murderer laughed. “Are you capable of visualizing shapes in your head?”

“I’m too tense to visualize!” But Rebecca, as this sort of person, did not really mind that kind of teasing. She was charmed by the attention. “I’m usually better. I’ve taken like half a dozen dates here.”

“Were any of them second dates?”

“One drink and you start talking shit.”

“You should see me at two.”

Rebecca gave her tallboy a prod with the rubber toe of her green club. It fell over weightless and empty.

“I’ll get us another round.”

The murderer walked with her.

Rebecca stopped her, “No it’s fine, I’ll be right back.”

“You know I can’t let you walk off.”

“Why?”

The murderer’s apologetic smile fell to confusion.

“Oh,” Rebecca hollered. “Right!” She threw her hands up. “Forgot!” she yelled. Because for a moment, she had.

◆

A few holes and sixteen ounces later, Rebecca’s clumsy putt sent her green ball speeding past the murderer’s red one, off the course entirely. Rebecca shrieked, chasing after the ball. It had speared through the clear water and sunk—it surprised her how fast—to a bowly bed of moss at the bottom of the course’s creek. It had seemed so likely it would float. Was it those dimples and their airy suggestions? The buoyant sound of its ricochets, perhaps? Shouldn’t that command the ball up, up, to her? But there it sank.

“Well? Are you gonna get it?” asked the murderer.

“I can’t just walk into the creek.”

“Just bend over and reach in.”

“It’s far! What if I fall in?”

“So? Are you afraid of drowning?”

Tipsy Rebecca flipped her hair back and mimed holding a microphone to her mouth. “Depends. Are you going to drown me, Elvira?” She put the microphone to the murderer, who couldn’t help but smile and turn away, charmed.

She tapped the invisible microphone and cleared her throat. She looked at Rebecca’s eyes and said, “I’d never do you that dirty.”

So Rebecca knelt down, reached as far into the cold creek as she could, and grabbed her ball. The sensation in her arm took her. Somewhere else, she went beyond the creek and let the chill in. She gasped when she felt the murderer’s grip helping her up. Their faces were level.

“If you can believe it, my name isn’t Elvira.”

“Can you tell me what it is?”

“No,” the murderer said, “but I’m about to.”

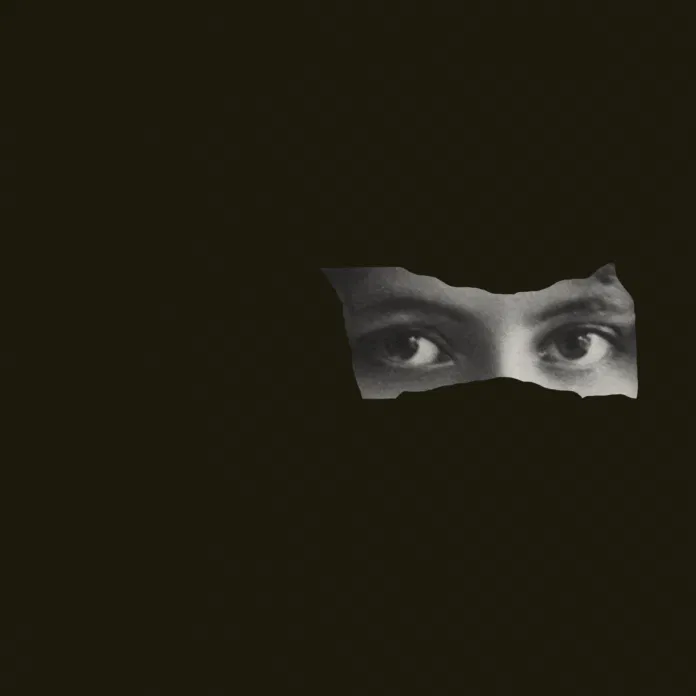

Rebecca stared at the murderer, frozen, and the beauty she witnessed was undoing— revelatory echoes of every face that ever floored her, across the murk of decades, right here as magnetic and deadly as divinity. These eyes of lost love. Those exact dimples trimming that exact smile. How could an impatient glance leave her trapped in the dawning fear that she would never see anything as hers as this woman’s mouth? Now it spoke.

“It’s Frankie.”

The sun would go down in two hours.

◆

At the Mets’ stadium, Rebecca spent two thousand dollars on the best tickets available. She pictured the bag of blood on the rug for which she went into debt, only briefly, how it would confuse the detectives investigating her murder, and she decided to splurge. She would be dead soon. But against the very instincts that drummed within her hours ago, she wanted to have fun with her murderer, Frankie.

During the opening pitch, the murderer asked if Rebecca thought they’d get to be on the jumbotron.

Rebecca responded, “Do you think you’ll ever murder anyone here in the crowd?”

The murderer hesitated. Then, “No.”

And hopeful Rebecca’s first thought was that this apparent moment of contemplation from the murderer represented a trace of doubt. She latched onto the reassuring feeling that maybe the murderer was experiencing the same thing she was, until—

“I’ve never been assigned to New York. Doubt I ever will again.”

They got nachos, and two more tallboys. Rebecca explained the rules and told the murderer about the mascot lore, the rituals between play, President Taft and the seventh inning stretch. Then, in the eighth inning, with the Mets down by two with two men on base, Lindor hit a home run.

Everyone went nuts. Out of their fucking minds. Rebecca grabbed the murderer and pointed to center field.

“Look at the apple! Frankie! The big apple! Bring that fuckin apple up, baby!”

The murderer was overjoyed at the big apple’s grand rise. They shook each other screaming, throwing their heads like knotted snakes, reveling in the energy they couldn’t possibly shake. They almost hugged each other, then turned to embrace the fanatics around them. A mustached man beside the murderer grabbed her arms and kissed her. She twirled to Rebecca in euphoric shock and they both started cackling. Nearly falling over, Rebecca and the murderer were forehead to forehead. She could hear the bone’s contours resonate, rubbing firm, under their thin layers of soft skin. They grabbed each other’s necks and kissed. Rebecca closed her eyes and saw them, together, can’t you see it, on the jumbotron, broadcast in the sky over the howling fans.

◆

It would never end. They held hands in the parking lot. The murderer apologized for her clammy hands, but Rebecca told her it was perfect, because hers were dry, and rough. “They are,” the murderer smiled.

The murderer said, “it’s time to take you home.”

No, Rebecca thought. “What if we don’t go home.”

“Then I have to kill you right here in front of everyone.”

“Would you really?”

“Yes,” the murderer said. Sober.

“Have you done it before?”

“Yes. You’ll get to be on the news. An unsolved mystery.”

Rebecca laughed.

“But let me take you home. I don’t want to kill you here.”

Rebecca felt Frankie’s knuckles between hers, and pushed away the thought of her strength.

◆

The moment Rebecca stepped into her apartment, she turned around and let out what she had been holding in. “But what about Coney Island? What about the Cyclone?”

“I’ll go on my own, before my flight,” the murderer told her, reaching into her jacket pocket.

“But,” the victim said, “how will you know how to get there?”

The murderer now felt her victim pulling closer, “I’ll look it up, on my phone.”

“But, but,” Rebecca smiled, “how will you know the shortcuts?”

“I won’t need them.” She only allowed herself half a smile.

Then Rebecca asked, “how do you know you’ll have as much fun without me?”

And Frankie said nothing.

Rebecca said, “you had fun today.”

“I did.” She let her shoulders fall. Her fingers curled deeper into Rebecca’s.

“So,” Rebecca sighed, “did I.”

They stared, into the other, until, seeing through fog, it was unbearable.

Without warning, oh no, Rebecca thought, though yes, wasn’t everything the rolling mist of warning, the murderer drove her victim into the wall by the throat. Rebecca felt her pulse knocking against the murderer’s fingers. Heard the leather jacket’s creaking twists. Her purse buckles chiseling through the eggshell paint into drywall. She wanted to squirm away, for the door, for the kitchen knives. Shouldn’t she try, shouldn’t there be more to summon, to live? Shouldn’t desperation kick in to become all powerful? But the murderer put her thigh between Rebecca’s, and she wanted only for her to press harder. Rebecca let her legs go limp. That thigh sent her heart flipping. The murderer felt Rebecca’s breath leave her throat, felt the air’s tickling hiss through her palm. A vein grew fat on Rebecca’s forehead, between her eyes, rolled back into the beyond of this last pleasure. She wouldn’t mind death if this is how it came.

Then Frankie released her. Rebecca felt the tongue. She gasped at mouthfuls of air between kisses. She bit her lips. Her teeth knocked into hers. It was violent and free and Rebecca didn’t think about breaks or blood in this moment. They unzipped, unbuttoned, flung undressed into each other. Frankie’s arms were so strong, but Rebecca wasn’t weak. Wet rimming cotton, full warmth, locks splashed over cheek and neck and breast. We were entangled and grinding raw bruises, slimy with sweat and cum. We slept soaking until the sun cast short shadows on the rug.

◆

When I rolled over, the morning blinded me. Your empty pouch was gone, but the rug held crusts of harmless brown blood between my two opened windows. The cafe’s merrymakers were clinking cup to table across the street, and it carried so clear, my dream fog pegged them for a small party in the kitchen. No. What was the dream? I couldn’t remember. Even now?

Your hair was smooth. I watched you step into your slacks. Your ankle carried a strap with a small, slim, dark knife in it. Blinking through the sleep, no it wasn’t a knife, just its empty sheath. Then it was gone. I took for granted that you would still let me bring you to Coney Island, but you said your flight had changed, asked me if I could be ready soon, and kissed my mouth askew, and when I turned to kiss you right, you held close and our lips smeared into each other. I knew you meant it.

◆

I think it was on the train, wasn’t it, where you told me everything you could remember? You were born in that region of Romania, or some place with a funny name, or misty map placement. Weren’t you? I’m embarrassed to admit I was distracted by all the racket. They were all going to Coney Island. And there we were. Oh right, it was part of my game.

“Let’s play a game,” I had said on the train.

“What’s the game called?” you asked.

“It’s called Stalling.”

“Ah,” you said, “it’s called Please God Don’t Kill Me,” you joked, and we laughed together, because it felt like a joke about before. See, remember Frankie, when my laughter faded before yours, and you sensed my fear, you squeezed my hand and lifted our knot of fingers to your mouth and publicly kissed my knuckles, and your squeeze and your kiss, they said, not anymore.

“Really though,” I nearly panted, “I do have a game.”

“What are the rules?”

“The rules are you have to guess the theme, and you have to answer my questions with whatever comes to your mind.”

You nodded in concentration and cocked your fists to make a show of preparing yourself, baiting a laugh that of course you caught.

“Enough,” I lied, “the first question is: what do you think of when you think of mermaids? Go!”

And you stunned me with your winding answer about your girls’ schools, housing friends and nemeses, inside jokes about penises made of pearls and childhood dreams of, finally, mermaids pulling you down kelp forests.

“So that’s what I think of,” you laughed. How wild. And on the train, mobbed by beachgoers, you didn’t even whisper like I used to. “Why was that the first question?”

“Because,” I announced proudly, “because every year, the mermaid parade happens on Coney Island. So now you’ve learned something about Coney Island and, even better, I got to learn who—learn something about you.”

You told me I was sweet, and that this was a very cute way to stall. But we weren’t stalling, were we, Frankie.

“Not anymore,” you said. The air conditioning gave me chills, my teeth almost chattered, and I asked you if mermaids’ nipples stayed hard forever.

“They do in my dreams.” You and your popping laughs.

The Q dumped us out in the tunnel, and we washed up onto the street’s hot bustle. It looked as glamorous as I wanted for you. The vendors were a perfect day’s devoted servants—awaiting and postcard-ready. Where I had dreaded your disappointment in their careless and plastic desperation, they weren’t plastic, no. They were coated, plaid parchment paper.

I nearly sang to you, “We’ll start with hot dogs and the Cyclone.” And you whispered under the hiss-spitting grill that you were surprised I wasn’t still trying to save our ostensible objective for last. But you winked, and with your wink I was freely yours.

“Two footlong everythings, please.” I nudged you, “Even if I were stalling, you don’t just ride the Cyclone once. We’re doing it first and last. It has to bookend the Coney Island experience. But between the two rides?” I explained why we had ordered from this specific hot dog stand. I sold you on the ferris wheel. I guessed right that you’d take the dare to rematch minigolf with ski ball, my made-up specialty. “The Cyclone is the palette cleanser,” I told you, “like ginger in sushi. In many ways, it’s the best part of the sushi.”

“What?” You asked.

“Well, maybe not the best part. It was just a fun thing to say. I’m not sure I mean it.” You still looked confused, so I went on, “you know how when you order sushi, it comes with the ginger? That’s what it’s there for. You cleanse your palate between pieces.”

The hot dog vendor overheard us, and shouted over the grill that that’s not what that’s there for.

“Then what is it for?” I asked.

He said to hide the fish taste, and you thought that was sooo funny.

Weren’t they delicious, those ugly hot dogs? You asked me if I’d be sick riding a roller coaster with a full stomach. I knew you weren’t the kind of person to say tummy, even cutesy.

“Iron stomach,” I reassured you.

The line to the Cyclone was long, but we didn’t mind. That man in his tacky jacket kept snaking across from us, so we faked a conversation about ballet dancers to hide our laughter. Or opera? Oh, I hope I haven’t already forgotten. But he did look, I remember you saying, like a wife beater, so the least we could do to punish him was deliver the nagging insecurity that he was being ridiculed by, I really remember you saying, two beautiful women.

When it was our turn to board, I threaded us through the group, hand in hand, to the caboose. A man with a braided bob in a tight blue polo took care to fasten us in. The bar didn’t budge under his strong shakes. “You good,” he said without looking. Safety: guaranteed. The second he stepped back to his podium’s corded intercom, I turned to you to say “Wow, that guy smelled—”

“So good!” We finished together and laughed. Your left thigh pressed against my right. This may not seem it, but it is the best seat, I explained, because each careening hurl and hump will fling us harder than the rest of the cars. Even the front seat’s unimpeded view is second to where we are.

You looked nervous, Frankie. I couldn’t believe it. Your chest fell and rose with these short breaths. I watched the clear cilia hairs get goosebumped to attention from your neck to the shadow between your breasts.

It started. We notched up the climb, and you wrapped your hand around mine. I swear I could remember your fingerprints like putty. Jesus, you said, it feels like this thing could collapse.

Exactly, I beamed, and pointed at the Remain Seated sign, “Solid advice, no?”

Your laugh beat your nerves. Get ready, I said, and we plunged into the timber’s tunnels and trusses. We were beaming freaks in the souvenir photo.

◆

And was I convinced by then, Frankie? I won’t lie: I was lying when I said I knew. Until the top of the ferris wheel. Your camera’s click was the hint of life, and with the sun nodding bit by bit past your itinerary, I couldn’t come that close to beating fate without tempting it for good. The stupid question, I asked, “what about your flight?”

Don’t worry about it was your promise to me. And mine in return was that now I wouldn’t. Everything tapped lightly against our world. When we’re leaving the swaying cabin I feel molten metal love between every untouching part of us. These feelings make me feel stupid, but you ease my grip on doubt.

On the pier I said the ocean was really unravelling me. You told me I didn’t have to talk like that for you to take me seriously. But you make me like talking this way.

“The sound of these boots on the pier is almost perfect.” I told you. “They used to take us on field trips to Revolutionary War camps, or Civil War camps. Just old hickory houses filled with old tools for making old things. Smells like sour coffee and smokey biscuits, glowing like eight in the morning. All these floors over empty cellars. All these two hundred year porches, knocking under my new boots for second grade. Probably my favorite sound in the world.”

“You’ll pick shoes just for that,” you pulled, “you’re so—” I was so kissed.

Us against the railing. Were you counting your heartbeats like me?

And when we turned away from the Atlantic’s squinting sunset, I thought I couldn’t hold it in. Yes, I acknowledge, three loves have told me that I share too soon and without caution, but you weren’t one of those people. Could you imagine, Frankie, what this day would have looked like if I hadn’t planted my heels, and let the taught tug of my long arm turn your stride around? I raised my voice over the surf, “Before we go back for another ride—”

Your comfortable smiling confusion pressed my nerves smooth.

“I just, Frankie, I need to say it. If I didn’t tell you, I’d explode. I can’t possibly stand in line for, for, for a rollercoaster, you know, with its anticipation and dread and thrills. It would be like a joke, Frankie, for us to just do that, after all of this, without saying. I’m sorry it’s on the pier, and so cliche, and I really used to think I was the kind of person who was better than cheesy moments like this. But you’ve humbled me, Frankie, in a way that makes me feel, just,” I was throwing my arms around, in practical hysterics, “completely reborn, as a person.”

“I know what you mean,” you said, through these newly wet eyes.

“I’ve never felt so much joy.” I thought about my words. “And devotion. Devotion. To you, from you. No day of my life has ever felt like this, you know? Does this sound oblivious? Am I losing my mind?”

“No, no,” you cooed.

“Right?” I laughed at myself for pretending to know you’d agree, when really I couldn’t have been more relieved. “I don’t know what this situation is.”

I told you that for two days I hadn’t understood a thing but you, and I couldn’t imagine feeling this kind of instant connection with anyone else.

“Isn’t this love,” I asked you. “Or, the promise of it? Don’t you feel it? Isn’t it incredible to you too?” We were both crying now, and you weren’t saying anything, but nodding.

You hugged me, running your arm up my back and your fingers through my hair. We did slow twists to the sighs of the crashing waves. There on that pier, before we went back to the Cyclone, I told you I love you, Frankie. I said to your eyes I wanted to try to spend forever with you.

You led your lips to my ear and whispered between the hush of my curls that you felt it more, you loved me more. Then you twirled me around, my back to your heart, and you cut my throat.