The Cube was dark and metal and bigger than us. It balanced on one of its points, and spun if you pushed it. The dad and I stood on one side of it, he and the mom on the other. We put our hands to the cold tin surface and pushed. This was fun for a while. Then we got used to it. The plaque anticipated our boredom. It said ALAMO.

“Alamo?” the dad said.

“I don’t know,” Julio said.

“Google it,” the mom said.

He googled it. “The name was selected by the artist’s wife because its scale and mass reminded her of the Alamo Mission.”

“Alamo Mission?” the dad said.

“The Alamo is a historic Spanish mission and fortress compound founded in the 18th century by Roman Catholic missionaries in what is now San Antonio, Texas, United States.”

They were nailing their lines.

“A cube reminded her of the Alamo Mission,” the mom said.

“Apparently a guy lived in it.”

“The Alamo Mission?” the dad said.

“The Cube,” Julio said. “No one lived in the Alamo Mission. People died there.”

“We should have raised you Catholic.”

“Your brother is a waiter now.”

“You told him that already.”

“I keep repeating myself.”

“He’s started taking these brain supplements.”

“My brother?”

“Your dad. Your brother does other drugs.”

“They’re not drugs, they’re supplements. I don’t want to forget you guys.”

“You already have.”

We ate dumplings from a cart. The parents wanted an authentic experience of the city. They weren’t visiting for tourist reasons. Still they wanted an authentic experience. So we took them to a cart. While we ate we discussed the aunt. She’d been thirty. Everyone was sad about her. In a general way, since they hadn’t really known her. Insofar as they were reminded of their own death requirement. She had died too soon was the consensus. Too soon for everyone else, no one said. For herself, she had died at exactly the right moment.

Julio needed a suit. The Cube and the dumplings were inadvertent. He needed a dark suit. We went to a clothing store. His mom explained this need to the girl behind the counter. The girl found him one. He tried it on, looked good in it.

“What do you think?” the mom said.

“Too dark,” the dad said.

“I was asking my daughter-in-love,” she said.

She had started calling me that lately. We had been together for almost three years, since the start of college. We had been together twice when we decided to be a couple. A couple is always deciding. You just forget after a while. That’s called belief.

“It’s nice,” I said.

“He’s so skinny it worries me,” the mom said under her breath.

“I can hear you,” he said.

“It fits perfectly,” the girl said. She ran her hands up and down his sides. She tugged at the button to see how much it gave. “Maybe we should go a size bigger so he can grow into it?”

“I think I’m done growing,” he said. “I’m twenty.”

“Really?” she said. She reappraised him. “So am I.”

He looked at me.

“Handsome,” I said.

“You’ll never wear a black suit,” the dad said. “Only at a funeral.”

“I’m going to a funeral,” Julio said, unbuttoning the suit jacket.

“My condolences,” the girl said, pulling the jacket from his shoulder. “In any case a man can’t really be said to have a wardrobe qua wardrobe without a black suit.”

“How old did she say she was?” the dad said.

Julio and his parents fought to pay for what neither could afford. In the end his parents won. He was bitter. His dad consoled him the only way he knew how: irony. “It’s an investment, bro. Paying for you now is our retirement plan.”

Outside it was colder than before. The mom asked if I had something warm to wear tomorrow. I said I had a good dress, leggings, a coat—the one I was wearing now. Was that all right? It was perfect. She was pleased but regretful. She should have asked me earlier, she said. I told her not to sweat it, she had the boys to take care of. She found this funny, then sighed.

We sat next to each other on the train. She admired the poem posted throughout the car. Something about a leaf. “Isn’t it beautiful?” she said. I agreed though I’d looked at those words dozens of times without seeing them, and still couldn’t really. Julio said it was corny. “You wreck everything,” she said. He thanked her and lay his head sardonically on her shoulder. A man with one eye asked for money. The mom provided some.

When had it been established, my going?

◆

Julio lived in a townhouse with some people he didn’t really know, plus Obie, whom he saw less now that they lived together. Obie had offered him the spot between terms, when one of the rooms became vacant. He took Obie up on the offer though it meant abandoning the guy he used to live with. He felt bad about leaving, he talked me through it, just not bad enough to stay.

I lived in the dorm’s high-rise counterpart. We’d made sure my suite was presentable. The couches were bare and the tables were clear and it seemed he’d even wiped them clean. A window stretched across the far wall. The sun had set but dark specks of it hung above the buildings that ran along the sill.

The window wasn’t as clean as I’d imagined, and there was a smell, faint, of something rotting. I thought the mom, who fixated on the window, her nose crinkled, would approach the glass, wet a finger, and wipe at the smudge with her sleeve, as when she doted on her son. She did approach the glass. “Jeez,” she said. “You have one hell of a view.”

I encouraged them to sit and asked them what they wanted to drink.

He was on his phone and didn’t seem to hear me.

“I have champagne,” I said. “Sparkling wine, technically.”

“You’re a technical woman,” the mom said.

“A scientist,” the dad said. “She likes precision.”

“I like answers.”

“I’ll stick to water,” the dad said, massaging his temples with thumb and forefinger. “God knows I had my fair share of sake with dinner.”

“That won’t be stopping me,” I said.

“Shocker,” Julio said without looking up from his phone.

“Ouch,” I said.

“Julio,” the mom said. “Say you’re sorry.”

“Sorry,” he said. He looked from his phone to his dad. “You sure you don’t want to head to bed? You had a long day. Tomorrow’s longer.”

“Your parents aren’t babies,” the dad said.

Julio returned to his phone. He’d become interested in it.

“I’m sorry about my son,” the mom said. “I’ll have water, please.”

“Sorry,” I said. “I forgot.” She was an alcoholic, decades sober. “There’s soda too but it’s sort of flat.”

“Water is fine,” she said. She sat beside Julio and slapped him lightly in the face. “Oye. Will you put that away. Your girlfriend is pouring champagne. Do you want some?”

When he hesitated: “Decide or she’ll decide for you.”

Just last week he was drunk on that couch. But he wouldn’t. He was weird about his parents.

“I’m all right,” he said, pocketing his phone. “Thanks.”

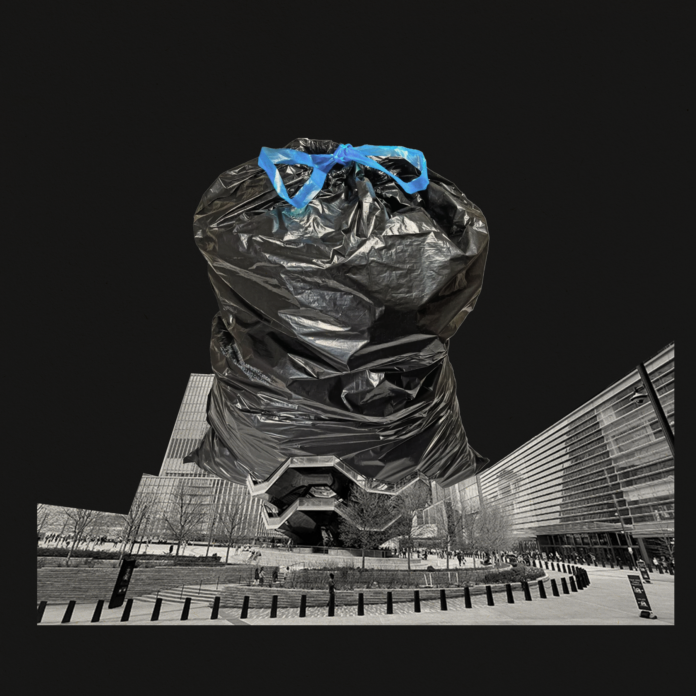

He followed me into the kitchen, which was siloed off from the living room. My phone was on the counter. The sink was empty and the dishware stowed but the trash bulged and stunk.

“Shit,” he said. “I forgot the trash.”

“I’ll get it.”

“No,” he said. “It was my job. I’ll do it.”

I barred him from the cupboard under the sink. “You bring them their drinks. I’ll handle the trash. It’s fine.”

“Are you sure?”

“I’m sure.” I pulled the bottle from the fridge.

“The one from Yadi!” he said. “I thought we were going to save that for a special occasion.”

“Isn’t this one?”

“Is it?” He filled three glasses from the tap. While it ran he held out the fourth. “You sure you don’t just want some water?”

I popped the bottle.

He shut the tap off and handed me the glass.

“Just one,” I said, filling it. “Don’t let me have more.”

“Deja,” he said. He kissed my forehead.

“What?”

“You know I don’t like doing that.”

“Well,” I said, downing half. “You just did.”

I thought I’d duck out of there with the trash in hand before he could apologize, but the bag was stuck in the bin, and he didn’t apologize, he just left. I struggled with the bag. I tugged at the edges and the edges stretched. I paused to drink. He came back from the living room. At the sight of me he laughed. He was laughing at me.

“What,” I said. I set the glass down. “I tried. The bag is stuffed.”

“Right,” he said. He came and scrunched the top of the bag in his hand and pulled hard. All that happened was the top ripped off. “Fuck.” He covered his nose with his shirt. A glass broke in the living room.

“Fuck,” the dad said, then entered the kitchen. “Where’s the dustpan?”

“In the closet by the front door,” Julio said.

The dad vacated.

I grabbed another bag from the cupboard and wrapped it upside down over the gashed one and Julio picked the bin up and shook it downwards and the old bag dove headfirst into the new one and I caught it.

“I can’t find it,” the dad said from the other room.

“Behind the coats,” Julio said. “It’s sort of buried.”

There was the crackle shards make when they rub against each other. The dad hurried back into the kitchen and poured them into a neat pile at the top of the bag, then left for the living room.

Julio tied the bag and made for the door.

“Hey,” I said. “I thought we agreed.”

“Fine.” He left the bag on the floor.

Of course the first thing the mom said when she saw me scurrying from the kitchen to the door with the bag in hand was, “You’re gonna let your girlfriend do that?”

Sometimes Deja, sometimes his girlfriend. Which one when depended on context, purpose. Here to maneuver him into shame.

“She insisted,” he said, and shrugged.

◆

It was good to get out of the apartment for a moment, even if out of the apartment just meant into the hallway. It would have been better if it meant quiet. But Friday meant a party on my floor. The hallway was clogged with bodies and stunk of sweat. A crowd sang a song I halfway knew, though I couldn’t remember having listened.

I’d just reached the trash chute when I heard my name. It was Yadi.

“You look great,” I said. The sort of thing you say when running into Yadi. An honest statement. She looked good. A crop top and high-waisted pants, scant for April but parties in our dorm were hot any time of year. Parties. I envied her. He rarely wanted to go, never for me to go without him. When we did, I was too aware of myself to stray much from what I was wearing now: a campus t-shirt that my mom had bought for me three years prior, and a pair of jeans that I’d pulled from the upper regions of my hamper.

“I look silly,” Yadi said. “I put on all this crap and I still don’t look half as good as you in a t-shirt.”

A lie. I waved it off. I held the bag with one arm and hugged her with the other. She was warm through her shirt and smelled of lavender. “What brings you round these parts? Please don’t say it’s for that.”

“Alas,” she said, bringing her hand to her forehead as if to shield her eyes from the lights overhead. She looked down the hall, past its random coagulants, as if someone were approaching from the other end. “You know Kate? Kate Castillo?”

“I think Julio does.”

“Her boyfriend lives on this floor. She’s having him host her twenty-first because he’s got the bigger place.”

“The uses of a man.”

“Ditch yours, come through. We’re late.”

“I wish. His parents are in town.”

“That’s right, I’m really sorry. How’s he holding up?”

“Fine, actually. They’re in pretty good spirits. They didn’t really know her.”

“How about you?”

“These are my feelings,” I said, lifting the bag.

“I’m dead,” she said.

The handle to the chute was sticky. With one hand I twisted and pulled, and with the other I set the bag’s fat bottom into the narrow square opening. The bag didn’t fit. Before I could stop her, she pressed hard with both hands into its top, right into the pile of shards. The bag went in but her palms were bleeding. She looked at them and sucked air through her teeth.

“Oh,” I said. “I’m so sorry.” I pulled her by the elbow down the hall. At the door I realized I didn’t have my keycard. It was attached to my phone, still on the counter. I banged with my fist.

Julio looked sick at the sight of her. “What happened?”

“Grab the first aid,” I said.

He tailed us into the kitchen, where he dug in the cupboard for the kit. I ran cold water over Yadi’s hands, then sat her at the table and set her palms out and pressed into them with a napkin.

Julio opened the kit flat against the table. “Is she going to need stitches?”

“Could you pass me an alcohol wipe?”

He fumbled through the kit, then handed me a wipe.

“This is going to sting a bit,” I said. I dabbed at her palms with the wipe. I wrapped her hands in gauze. They were small, a girl’s hands, oddly stubby.

“Deja, what happened?” The mom. I’d almost forgotten she was there. The dad too. The three of them stood at the end of the table, looking at me.

“I was just helping her with the trash,” Yadi said.

“It was the glass,” I said.

“Pobrecita,” the mom said.

“It’s not so bad,” Yadi said.

“It looks pretty bad,” the dad said.

“Will she need stitches?” Julio said.

“The cuts aren’t deep,” Yadi said. She stood. “I’ll be fine. I’ll be the ‘before’ shot of a scar cream commercial, but I’ll be fine.”

We laughed. Then we stood there as if waiting for something. In the distance was the din of hallway traffic and the rumble of a subwoofer. In the air hung the faint stink of trash.

◆

Until Yadi came along I’d thought the parents liked me. Maybe they’d thought they liked me too. Sometimes all it takes to see how little you like someone, how little someone likes you, is for someone better to come along. To see someone struck with that knowledge, even if that someone is oneself, is usually embarrassing.

Maybe that embarrassment made Yadi thank us for our services and try to head on her way.

“Why the hurry?” the mom said. “Stay for a drink. Deja needs help with her champagne, you know. These bums aren’t having any.”

“She’s running late,” I said.

“What, are you eager to have her go?” the mom said. “If you’re already late, what difference does a few minutes make?”

“Deja invited me too,” Yadi said, “and it’s very kind of you to offer, but—”

But the mom wasn’t taking no for an answer. She had already left for the kitchen, where she grabbed a few glasses, the bottle of bubbly, and the jug of soda—she often carried more than seemed humanly possible—and plunked them on the living room coffee table. “Sit,” the mom said, and she sat.

Yadi sat in the chair at the far end of the table, the window behind her. Outside, darkness was complete. The window had turned mirror. I ignored my reflection and sat in the chair at the near end, facing Yadi. Julio sat between his parents, the dad nearest Yadi, the mom nearest me, on the couch, which ran the length of the table, where there was a phone, facedown, playing salsa.

“Rubén Blades?” Yadi said.

“Yep,” the dad said. “Didn’t you and Julio meet him? I think I saw the picture.”

Julio poured a soda for his mother and a bubbly for Yadi and himself.

I hadn’t seen the picture, or known it existed.

I’d ask him about it later. Or I wouldn’t. I wouldn’t ask him why he hadn’t mentioned it. Either he’d kept it from me or he’d forgotten to share. Whatever the answer I’d be hurt. Whatever the hurt it would be stupid. He’d apologize, I’d apologize, we’d both feel like shit.

“One for me too please,” I said.

He obliged.

“Such a sweet guy,” Yadi said. “I told him Julio’s folks were from Panama and he was hyped.” She smiled at Julio as she took her glass. “Julio was chill, super nonchalant, not at all phased by his celebrity or whatever. But I could tell he was about to, like, shit himself.”

The parents laughed. The dad leaned back in his seat and rubbed his hand absentmindedly on Julio’s back, as if wiping off grease. “Bro, tell me you got his autograph.”

“Yeah, I asked him to sign my boob,” Julio said.

“Degenerates,” the mom said. “Complete degenerates. Mija, what misfortune came into your life for you to know my son? And, you know, what’s your name?”

Yadi said her name. “I’d, you know,” and here she mimed a handshake, “but, you know,” and here she held up her bandages.

The mom’s laugh was disproportionate. “You’re not mocking me now, are you.”

“A little, maybe,” Yadi said. Her boldness seemed only to draw the mom in further. “As for misfortune, she came to me in the guise of Professor Gloria Ramírez, instructor of the ethnomusicology course I met Julio in.”

“She’s so boring,” Julio said.

“Julio has a hard time valuing the intellectual contributions of women,” Yadi said. “We’re working on it.”

“Oh my God,” Julio said.

“Professor Ramirez is unfortunately beyond even my faculties of appreciation.”

“What’s her deal?”

“Operation drab,” Julio said.

“Drab o’clock,” Yadi said.

They were jumping from the same lexical cliff.

“I’m confused,” the mom said.

“So were we,” Julio said. “If it weren’t for radio, I’d have been put off Latin music forever.”

“You guys buttressed each other,” I said.

“Someone’s been GRE-prepping,” Julio said. “Our show was a bulwark.”

“What against?” I said.

“Show?” the mom said.

“They do radio together,” I said.

“Right!” the mom said without looking at me. “I was wondering why you sounded so familiar. You have a good voice, you know. This one tunes in to . . .”

“Brujx.”

“Brujx. Right. This one tunes in sometimes.” She fondled the dad’s ear lobe. This gesture of affection always teetered on violence.

“Really?” Yadi said. “I usually figure there’s no one out there but the weird old guys who call us in the middle of the night.”

“I mean . . .” the mom said.

“Whatever,” the dad said.

She pet his scalp sympathetically. He removed her hand.

I listened too. I hadn’t always. In the beginning, I’d attended his shows in person. It was just him then. We’d go to the station together, wings and fries in tow. Some nights he brought me into the vault and told me to pick something out. In Master Control he played what I’d picked. The world thought he was DJing for it. He was DJing for me. I was DJing. But I wouldn’t go on air, not even when he asked me to. I didn’t like the sound of my voice. It didn’t sound like me.

Other nights he left me in Master Control and came back from the vault with an armful of seventies Chilean records which he dusted and spun into the morning. Some nights we had homework and he was just manning the ship. We worked. He broke a few times an hour to flip the record, tell the listeners what they’d just heard, what show they were listening to, as if anyone could have gotten there by mistake. I won’t say it lost its novelty. We just got busy. So I stayed home and went to sleep or stayed up working until he was done and rejoined me or texted me that he was headed to his place for bed or to the library for a late night with Obie.

Then he met Yadi. When he found out she was also a programmer at the station they started doing shows together. Suddenly I wanted in again. But I thought it’d be suspicious, it’d let on that I was suspicious, if I started going again now. So I just listened from my room. I tried to gather from their conversations what they said to each other when the microphones went dead. I wasn’t sure what was worse: being talked about (having to be talked about) or being elided altogether.

Yadi now said something pretentious about radio being a graveyard for lost souls, a sonic wasteland traversed only by kids in hazmat suits and the walking dead.

“You kids are too smart for your own good,” the mom said.

“Some of us are smart,” Yadi said, “and some of us are geniuses.”

“Don’t flatter him,” the mom said. “He already has a big head.”

“It’s not your son I’m talking about,” Yadi said. She looked at me and the mom’s eyes followed. “She’s a once-in-a-generation biologist, is what my science friends say. Darwin is pretty much rolling in his grave.”

“There are other reasons for that,” I said.

“Remind me of your research?” the dad said. “Protons, right?”

“Prions,” Julio said.

“Prions,” the dad said.

“Proteinaceous infectious particles,” Julio said. He looked at me. “See? I listen.”

“You want a trophy?”

“Oof.”

“That came out harsher than I meant.”

They all looked nowhere. I think they were shocked. We weren’t fighters. We were tongue-biters. But an audience can embolden you.

“Damaged proteins,” I said. “Misfolded, we call them.”

“What this one does to a towel,” the mom said.

“Except they make your brain Swiss cheese,” I said.

“I have a fear of holes,” the dad said.

“I like the pomegranate,” Julio said. “A hunk of rot blooming inside a pomegranate. I guess rot is stretching the metaphor. But it has a ring to it.”

“Gets at the ‘infectious’ part,” the dad said.

“It’s a bacteria,” the mom said. “Bacterium.”

“No,” the dad said. “Prions aren’t alive. Boil them, disinfect them, whatever. They keep misfolding.”

“The scalpel,” the mom said. “I’m remembering the scalpel. Deja said they can wait on an unused scalpel for years.”

“They wait and they wait.”

“They’re patient, prions. They’re opportunists.”

“Game recognizes game,” I said. “It’s a new field, so there’s a lot to be discovered. A lot of grants.”

“And a lot of competition,” Julio said.

“Which she’s wiping the floor with,” Yadi said. “You know, it’s been in the news on campus. She just won one of the most prestigious scholarships out there for grad school.”

“And you didn’t tell us,” the mom said.

“You know how she is,” Julio said.

“And you didn’t tell us!” the mom said.

“I did!” Julio said, shielding himself. “I told Papa.”

She went at her husband.

“I’m sorry!” he said. “Ay, Yadi, mira que masacre.”

“Well deserved,” the mom said, “very well deserved. I can’t say I’m surprised. Let’s make a toast.” She held up her glass. “To Deja, for giving us hope in the universe, even when our men fail us miserably.”

“To Deja,” Yadi said, raising her glass, “for being as humble as she is smart.”

Julio then raised his glass, still full, and said: “To Deja.”

“Salud,” the dad said, and we drank.

Another glass, that gulp. “It’s Yadi we owe thanks,” I said, refilling my glass and hers, “for this bottle.”

Julio stood and scooped the empty bottle from the table, then carried it to the kitchen.

“I brought it to a function we had last weekend,” Yadi said, “celebrating the scholarship.”

“You had a party?” the mom said.

“It was a surprise,” Julio said from the kitchen. He came back with my phone and gave it to me, then sat again between his parents. “I conspired with Deja’s suitemates to host a get-together. You should have seen the look on her face.”

“Here,” Yadi said, leaning over the coffee table to hand the mom her phone. I could see the screen. It was dark until a square of light appeared. Julio and I, silhouettes. The lights come on and the crowd yells SURPRISE and the camera pans across a row of beaming faces and a banner labeled CONGRATULATIONS and then back to me, in full view. I hold an arm across my abdomen. The voice isn’t mine, but my lips are moving. Gosh, I say, you shouldn’t have. The camera zooms in on my face. He kisses me, a bottle in hand, he kisses my cheek. Then he pops the bottle and the video cuts.

“Adorable,” the mom said. She handed the phone back to Yadi. “You’re a rock star.”

“Hardly,” I said. “We partied like rock stars though.” I unlocked my phone and pulled up a video of Julio from later that night, sitting on the same couch he sat on now. In the clip he brings a plastic cup to his lips, or to what he thinks are his lips, and dribbles onto his hoodie. Then he laughs and says, as in all the videos I have of him, Are you recording me?

I’m not sure how I expected his mom to react, only that I didn’t expect her to react as she did: with an unamused look, directed not at me but at him. “Cute,” she said.

“It was water in that cup,” he said. “You should be proud of me for hydrating.”

“I’m proud of you all right,” she said, handing the phone back without looking at me. “I’m proud of you and your brother both. I could explode of pride.”

“Never let fear and stupid pride make you lose someone who’s precious to you,” the dad said.

“Okay,” the mom said. “Yadi, we’ve been holding you hostage.”

“Not at all,” Yadi said, standing, pulling her top back over a bit of shoulder that had come uncovered. “But yes, I should go, so I don’t worry my friends.”

“Why don’t you join in on the fun?” the mom said to Julio. “Your dad and I are tired.”

“Mama,” he said. He stood and collected the glasses and brought them to the kitchen. I trailed him. While the others made a farewell rustle in the living room he hissed at me.

“What?” I said.

“Why would you show her that.”

“I thought it would be funny.”

“You thought it would be funny.”

“I’m sorry. I’m an idiot.”

“You’re not an idiot. Don’t make this about you.”

“I’m not—”

“Just tell me how you thought it would be funny for my mom to think I’m a fuckup.”

“Does that video make you a fuckup?”

“You know she’s an alcoholic. Why the fuck would she find that funny.” His face softened. “Oh, don’t cry.”

I left the kitchen and went to my room. In bed I looped the act in my head, which still spun from drink. Each time I thought of the mom’s look as she said that word, cute, a sinkhole opened in my chest. I picked up my phone and scrolled. I couldn’t even do that. He was soon back in the room saying that he was sorry and that he’d been cruel, it wasn’t a big deal, his mom didn’t really care about that kind of thing.

“I’ve ruined things,” I said. “Your mom hates me now.”

“My mom doesn’t hate you.”

He left and came back with her and she stood beside him. It was only when he left her with me that I spoke.

“I shouldn’t have shown you that.”

She sat on the bed. For a long time she just sat there.

“My mom would say,” she said, “if you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.”

◆

That night, while he brought his parents down to his room, I lay in bed waiting for him. He was gone a long time. At some point I fell asleep. I dreamed we were waiting for the 1. To board we had to lower ourselves onto the tracks, which were submerged in water. The train splashed by on the middle track and we hopped on. The doors latched shut and I took the only open seat, next to a woman with dark hair. I could see him further down the car, holding on to a strap. My hand lay at my side. She held it. Her hand was wrapped in gauze. I woke up in the night and saw the hand was his. In the morning he was at my desk, writing in his notebook. Usually when I woke up he swiveled toward me and slid my way, then stood and kissed me or got into bed to lie a while before we both got up. Today he looked at me and then looked at his notes.

“What are you working on?”

“Nothing.”

“Are you writing about me?”

“Yes.”

“Can I read it?”

“No. We’re late.”

I put on my dress. He put on his suit. We met his parents in the courtyard. They looked haggard.

“Your brother can’t make it.”

“What? Why?”

“His flight got canceled.”

“Storms, they said.”

“Really? It looks fine out to me.”

“Sounds fine too,” the dad said. “What the hell kind of birds are those.”

“Fake ones. The university plants speakers.”

“Go figure,” the dad said. “You know, it might just be talk. Bad weather, this and that, when really there’s something going on they don’t want us to know about.”

“Do you hear yourselves,” the mom said.

We caught the train down to Hudson Yards. The church was there, just off what the pastor said was once called “Death Avenue,” because freight rails were built in a pedestrian zone and a bunch of people died. “A boy named John Murray passed on in 1911,” the pastor said. “Five years old. He slipped on a wet flagstone and was decapitated.”

The mom googled “flagstone.”

“This church is kind of a shithole,” the dad said after the service. “In an endearing way.”

“Lived-in,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said. We were by the cheese, eating. Julio and the mom were approaching from afar. “I probably shouldn’t partake,” the dad said. “I keep thinking of prions.”

“No, man,” I said.

“And she’ll suffer on the drive home,” the dad said.

“She’ll manage,” I said.

“She always does,” he said. “A veritable manager, she is.”

“What does that make you?”

“I’m her kryptonite. I forgot to put the window down once and she sort of puked.”

Julio and the mom reached us. “Is this Cotswold?” she said, having a piece from my plate. Then she looked at her husband and her face shifted. “Is he eating that.”

The dad went on speaking to me. “Just a baby puke,” he said. “She swallowed it.”

“Hey,” she said. “Are you eating that.”

“I’m coping,” he said.

After the service we toured the Vessel. It was new, then. No one had jumped yet.