◆

First Potato

Did you know that the first potato ever grown in what would later become the United States of America was grown in Derry, New Hampshire? Did you know that Alan Shephard, the first American in outer space, had roots in Derry, too? Lifelong resident Maggie Willard knows these things. Something else that Maggie knows: she’s a slob.

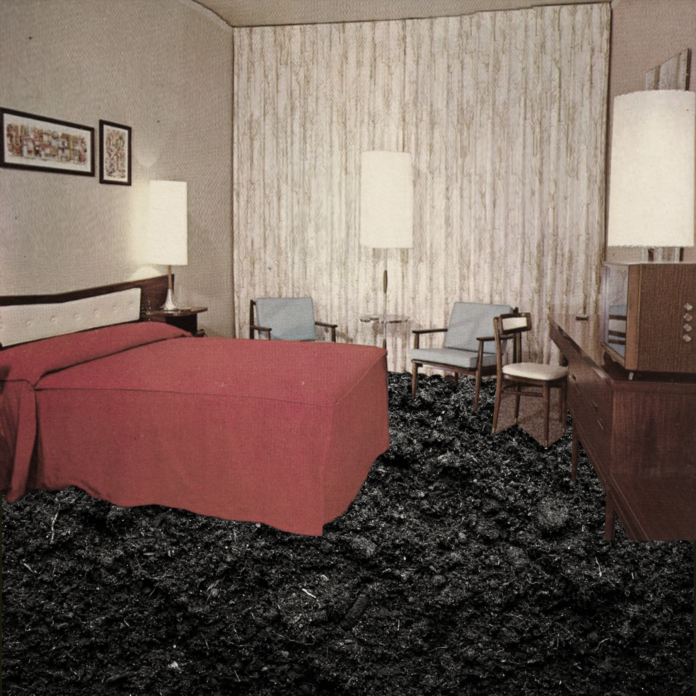

“I’m a slob,” says Maggie to her piles. In her kitchen, the piles grow mostly from the top of the fridge, the counters, and the center island. Throughout the rest of the farmhouse, Maggie’s piles line the walls, cushioning a few feet into each room at the floor and tapering off toward the ceiling. They’re composed mostly of newspapers, shopping bags, and mail she’s been meaning to go through, and they’re still there because Maggie understands her own, unconquerable nature. Even if she found the time or the drive or whatever it is that she’s missing to clear them away, they’d just spring back up again, albeit with a slightly different composition. Different newspapers, different shopping bags, whatever. She’s a slob. A person who, given time and space and items, will accumulate.

◆

Warn Your Bugs

“You’re only coming home because of the finger,” Maggie says when Myrtle, her older sister, calls from California to inform her of the visit. It’s February, but the temperature has spiked all the way up to fifty-two degrees. Maggie stands on her front porch in her bathrobe, letting the smell of melting snow waft over her as news trucks roll by. Maggie, warm-ish breeze ruffling through her hair, is simultaneously alarmed and curious about the finger and peeved at Myrtle, selfish Myrtle. When they were children, she’d been Myrtle the Turtle, a nickname that, to Maggie, had perfectly exemplified Myrtle’s slow, stubborn, older-sister soul.

“Well, yes,” Myrtle is saying, “Coming home is a very fraught thing for me. Does the house still have bugs? Should I book a room somewhere?”

“The house does not have bugs.” Maggie inhales to wrangle the hurt. When Myrtle last visited four years earlier, she’d taken the screens out of her bedroom windows, got eaten alive by mosquitos, and accused Maggie of having bedbugs.

“I don’t see how that’s possible, but okay. Unless you want me to stay somewhere else. Be honest.”

“Of course I want you to stay with me,” says Maggie, thinking the assertion a polite, necessary lie. But, as Maggie waits for Myrtle’s response, that old knife of longing turns in her chest. Her sister, her sister, her sister. A news van splashes past through a puddle of slush. An early blue jay lands in a naked shrub.

“You’re lying,” says Myrtle, “But I’m staying with you anyways. Warn your bugs.”

◆

The Finger

“The weather was so glorious that I just had to get out and putter around,” Kathy Zeigler, Maggie’s three-doors-down neighbor, told the reporter from Channel Nine News. “I hadn’t trimmed back my asters before the first storm last fall, so it was a real mess out there. You know how flowers get under snow? All black and slimy? And then the finger! The finger was nearly perfect!”

The news outlets reported that it was an index finger, three inches long. Though neither the prints nor the DNA matched anything in police systems, forensic scientists were able to identify the chip of blue polish on the northeast quadrant of the nail as OPI’s “My Dogsled is a Hybrid,” the gel variety, professionally applied. So far, no one has come forth to claim it.

◆

Myrtle Arrives

When Maggie pulls up to the airport, Myrtle’s waiting on the sidewalk with two rolling bags and a matching computer satchel thing. The larger of the two rolling bags is tagged with a neon pink sticker that says OVERSIZED. The smaller of the two rolling bags is misshapen, bulging and swelling at the seams. Myrtle, who’s wearing some kind of hippie muumuu thing, struggles to keep the bags upright. Maggie puts the van in park and gets out to help her sister. She only has to glance at the bags and Myrtle’s off:

“Why is it a virtue to pack light? Who decided that? Is someone who brings less stuff really so much better—no, not better: morally superior, because that’s the level of judgement we’re talking about—than someone who brings more stuff? Am I supposed to wear the same pair of shoes for two weeks? I like a wide variety of activities that all require very different footwear. That’s a good thing. And I’m not going to limit myself just so I can walk around the airport with my nose in the fucking air.”

Two weeks. Maggie’s heart does a fluttery dance. She lifts the medium-sized suitcase into the trunk, letting Myrtle handle the large one. They get in. Maggie drives.

“What do you want to do while you’re here?” Maggie asks.

“Can we actually be quiet on this drive?” says Myrtle. “It was a rough flight.”

“Oh, okay.” Maggie drives on in silence. Globs of snow slide off branches, landing in powdery explosions on the street.

“I love you though,” says Myrtle.

Maggie smiles. Some important scar tissue melts away.

◆

When They Get to the Farmhouse

Maggie watches Myrtle survey her piles from the front door.

“There are worse things,” Maggie says in defense. “I’d never hurt another person.”

◆

What Will You Do?

Home from work, Lauren Rockland, twenty-nine and living alone in Derry, sits on her couch with her coat and shoes still on. She scrolls. Pictures of friends, pictures of friends’ pets and babies, someone she knew in middle school has made some delicious looking chicken tacos for dinner! Lauren goes into her camera roll, finds a picture of herself doing down dog in leggings and a sports bra, and posts it with the caption Every big change starts with a little change. What will you do today to transform your life?

Lauren places her phone face down on her knee, counts to twenty, then flips it face up again. Seven likes! She returns the favor by liking each of the likers most recent posts. Some comments appear. Sammie_Lynn22 says “love this sentiment!” and blissfullywandering1872 says “ughh so jealous of that bod” with a kissy face. Lauren’s bod is quite good. She knows this, hence the sports bra pic.

Just as she’s about to put down her phone and exercise for real, that coveted little one pops up near her blue arrow. Lauren clicks. It’s Danny Switzer, who she hasn’t spoken to since high school.

Danny: any hot takes on this madness?

Lauren: madness?

Danny: the finger.

Lauren: I guess it’s scary but the police are on it?

Danny: haha. Ive been really messed up about it and looking at your feed because you usually have pretty deep stuff to say

Lauren: wow thanks! I have to go now, though.

Danny: haha ok bye have a nice night

Despite the goodbye, Lauren finds herself waiting for Danny to type another complimentary thing. What else does he understand about her elusive self? But Danny says nothing. Lauren grips her phone and remains on the couch, surveying her dark living room. She should get some stylish plants, a pet, someone to love deeply as proof that she’s living a meaningful life. She should find… a calling? Lauren twists the mole on the back of her neck. Astonishingly, it comes off in her fingers. Lauren gasps and throws it across the room. She fingers the new hole beneath her hairline. It’s warm and slightly sticky with blood.

“Woah,” Lauren says to the dark room. She goes into the bathroom for a Band-Aid, careful not to stick the sticky part on her hair. Once the Band-Aid is in place, she’s seized by dread and regret. She threw a part of herself across the room! Lauren rushes back, drops down to her hands and knees, and spends a good part of the night searching for the thing. She doesn’t find it.

◆

More about Potatoes

It was a potato farm when they bought it in the sixties, but Maggie and Myrtle’s parents never grew potatoes. Instead, they sold off parcel after parcel of farmland to developers, growing subdivisions and their own net worth. Maggie and Myrtle grew up wealthy by Derry standards. The family went on vacation, sometimes via airplane, once every year. When Maggie was in the fifth grade and Myrtle was in the eighth, their parents renovated the farmhouse’s kitchen, which, to the girls’ knowledge, was something that only happened on tv.

“Do you think we were spoiled?” Myrtle asked Maggie after Mom died. They were signing some papers to divide up the trust.

“Yes,” said Maggie. “I do.”

“It’s such a bummer,” said Myrtle. “If we were going to be spoiled, I just wish our parents could’ve been a little richer. This money won’t go far in LA.”

◆

On One of These Vacations

The family stayed in a bed and breakfast that Mom, Dad, and Myrtle considered charmingly historic but ten-year-old Maggie considered unbearably spooky. Maggie and Myrtle’s room had a queen-sized four poster bed that Myrtle claimed, a twin cot wheeled in for Maggie, and an attached bath with a clawfoot tub. In the night, from the cot, Maggie saw a witch in the bathroom mirror.

“Myrtle?” she said. “I’m scared. Can I sleep with you?”

“No,” said Myrtle, thirteen.

◆

The Sisters Drink Some Bottles of Wine

“Let’s drink out on the porch,” says Myrtle on the third night of her stay.

“It’s going to get cold when the sun sets,” says Maggie.

“Bundle, then.”

Maggie, forever the younger sister, layers up and meets Myrtle on the porch. Myrtle is wearing a pair of their father’s old wool socks for gloves. She pours Maggie a glass of wine with surprising dexterity. The sisters sip. Across the road, the sun shrinks to a winter pinprick behind the naked trees. Because she gave in so easily to drinking out in the cold, Maggie becomes determined not to be the first to speak. She sneaks a sideways glance at her sister, whose profile is astonishing. That crooked nose, that sagging pouch of a throat—when did they get so old? Growing up, it was a family fact that Myrtle was the pretty one and Maggie was the nice one. Now, Maggie thinks that maybe Myrtle wasn’t so much prettier, just more demanding. Also, Maggie doesn’t feel nice. “Easily defeated” is probably more accurate.

Some kind of bird-of-prey lands on the mailbox. The front yard mud begins its nightly re-freeze.

“Are you happy?” Myrtle asks.

Maggie snorts. She laughs with her hand over her mouth, trying not to spit out her wine. No, she’s not very nice.

“Well, fuck you, too,” says Myrtle.

With deep breaths through her nose, Maggie calms her laughter. She swallows the wine. “I’m sorry,” she says. “I’m listening.”

Myrtle shakes her head and crosses her arms. A car drives by, too fast.

“Myrtle?” Maggie says.

“I don’t know what’s so funny about happiness. I’m trying to check in because I love you.”

Myrtle rearranges the sock so she can grip the stem of her wine glass. “I’m on a journey. I’ve been analyzing my own unhappiness and working on myself.”

Instead of responding, Maggie sips. For the first time in their relationship, she feels she has the upper hand. Myrtle is still duped. For decades, Maggie had been duped herself, worshiping the false upward curve of life. All she needed was to scramble over this rock and mount this ridge and then there she’d be: a person, living. Now, she understands. The feeling of ascent is gone, and whatever was glittering up ahead has disappeared from the horizon. There’s no life to attain, no center to stand in.

The mailbox bird spreads its wide wings and pumps itself upward then away.

“So you’re not happy with your life?” asks Myrtle.

“Jesus,” says Maggie. “Of course not. What kind of person is happy with their life?”

“Let’s do something about it. We can put work in. Together.”

Maggie smiles.

“Do you like living here?”

“What do you mean?”

“There’s got to be some young, energetic couple that would kill to restore this place,” Myrtle says. “Refinish the floors, plant a vegetable garden out back.”

“I like living here. It’s free.”

“Okay.”

“Okay.”

Myrtle gets a second bottle of wine from inside. Conversation turns to other things. They gossip about people they used to know together as kids and take turns exchanging stories from their separate, adult lives. For Maggie, it’s agony. When Myrtle is away, Maggie is able to convince herself that she’s at peace with their separateness. But then Myrtle visits and the life they could have shared peeks in around the edges again.

“I’m going to bed,” Myrtle says.

Maggie stays shivering on the porch for a while trying not to feel abandoned. When enough time has passed, she brings the wine glasses inside, washes them, then goes up to her own room. The dresser drawer squeaks as she’s taking out her pajamas. Though this dresser has been hers for more than a decade, the sound still reminds her of her mother. Through the wall, Maggie hears Myrtle whispering to someone on the phone but can’t make out any individual words.

◆

Danny Switzer Finds Something in a Snowbank

“Go break up the snowbank so that it melts faster,” Danny’s manager says. She likes to tell him why he needs to do obvious tasks because she gets off on believing that her subordinates are morons. To spite her, he brought his phone out with him. Danny thumbs through his feed until he lands on Lauren, smiling over a steaming mug. She’s posted a bird’s eye of her boots. In the caption, she gives advice. She describes how New Hampshire winters pose a conundrum for the stylish woman—slim, attractive boots often fail in ice and snow—but, in this cute but versatile pair, Lauren has reached mecca.

Danny spots a leaf frozen a few inches below the surface of the snowbank and decides to hack towards it. He pries away a chunk of impacted snow—the leaf flips up with it. But it’s not a leaf. Danny bends for a closer look. The thing is fleshy and folded, hard but flexible, bending when he pinches in its sides. An ear. He turns it over. There’s a black clog of blood where it was connected to the head.

He drops it.

“Hey! Hey! Hey! Hey!” Danny shouts, to no one in particular. His pulse throbs behind his eyes.

◆

Morning Exercise

Maggie wakes a little hungover, but the day is bright and so her mood is buoyant. She laces up her sneakers and heads out for a powerwalk to burn her headache off. Rivers of melt make the asphalt shine beneath her feet. Icicles fall from front eaves, shattering in the yards below.

Maggie passes Kathy, who is tending to her front garden again.

“Looking for the rest of that corpse?” Maggie shouts from the street.

“Ha!” says Kathy. “Did you hear they found an ear in the Market Basket parking lot?”

“You don’t say.”

“And how about that virus? My niece might have to cancel her honeymoon.”

Maggie puts her hand over her heart. “What a shame,” she says. “Which niece?”

“Samantha.”

“Sweet girl. Give her my love!” says Maggie, powerwalking away. A pair of eagles circle above, passing over the midmorning sun.

When Maggie arrives home, Myrtle is on the living room rug with her phone doing a workout video. Maggie moves a paper bag of tangled yarn to the floor and sits on the couch. She surveys her piles, her home, her life. She watches her sister, middle-aged but still trying for abs. She has a couple thoughts. Myrtle, because she is her sister, sees those thoughts on her face and pauses the video.

“I’ll help you get out of here,” Myrtle offers. “I won’t go until it’s all finished. I can cancel my return flight, no charge.”

“I ran into Kathy. She told me they found an ear at Market Basket,” says Maggie because, though she means thank you, I need you, I’m lost, she can’t say it.

Myrtle hugs her because she understands.

◆

Maggie’s Piles

In the pantry: decades and decades of spices covered with some kind of sticky residue plus dust. A shoebox full of spoons that don’t fit in the (overstuffed) silverware drawer. Plastic ice cube trays, cracked, standing upright behind a box of unopened (and dusty) Graham cracker crumbs. One brilliant copper pot and many tarnished Teflon ones, most with wobbly or missing handles. Two grandmothers’ collections of crystal. Another shoebox, this one full of string and buttons. Five jars of peanut butter, eight jars of pickles, and four boxes of Duncan Hines cake mix so old that the reds on the packaging have faded to pink. Many bottles of many different types of oil, most with only a finger of liquid left in the bottom. Mismatched glassware, chipped mugs. They take it all out and lay it on the floor.

“I couldn’t have gotten rid of any of this stuff without you because it belonged to Mom and Dad,” she says, “I needed to wait for you to come for long enough to do this.”

“I wouldn’t have been too upset if you’d thrown out their peanut butter,” Myrtle says. She picks up a crystal bowl. “How much do you think this is worth?”

They make piles out of the piles. There is the obvious trash and the obvious sell, the stuff that they will try to sell but probably won’t be able to, and the stuff that they will donate.

“I need a break,” says Myrtle, so they go outside for a stroll. They stroll by Kathy getting her mail.

“Myrtle Willard I thought that was you,” she says. “What are you doing here? Just a visit?”

“I’m back to help Maggie clear out the house,” says Myrtle. “We’re selling it. It’s time for her to get up and go.”

“Go! Where to?”

The winter sun shines bright and there’s songbirds in a bare dogwood in Kathy’s yard. The promise of it all buoys Maggie. “Spain,” she says. “Barcelona.”

Myrtle grabs Maggie’s hand and raises it above her head. “Me too,” she says. “We’re selling the family farm and moving to Spain together.”

Together. Maggie’s heart soars, tightens, soars. The rest of the important scar tissue liquifies.

“Oh bring me!” says Kathy. “Sell my kids! Sell my husband!”

In the afternoon, Myrtle empties out all Maggie’s kitchen cabinets and then announces that she’s going to take a nap.

“Seriously?” asks Maggie.

“I’m jet-lagged,” says Myrtle.

Maggie sits on the floor of her messier kitchen, fuming. Though it’s barely fifty degrees, she opens all the windows and lets the wind push things around for a bit. Some onion skins whisk across the floor. A stack of mail blows off the top of the microwave. The family chore chart falls from the fridge onto the floor.

◆

Lauren, Alive

At the elementary school where she’s paid to follow a boy named William to all his special classes and meetings, Lauren rehearses reality. I’m a woman, alive, she thinks. I bought some boots; I’m planning on buying some succulents; I might schedule a get-together with a friend! I am so full of blood, she thinks at passing faculty and students alike. Can you see me, pulsing with true existence? They head down the east corridor to the district social worker’s office for William’s weekly appointment. William is dragging a marker along the wall, making a long red line, but Lauren, busy rehearsing, does not quite realize what’s going on until she sees another aide walking their way and eyeing them. Lauren turns to William. He is her constant companion for seven hours every day. She feels a mixture of overwhelming love and resentment each time she looks into his sad little face.

“William,” says Lauren, “I notice that you’re writing on the wall with marker.”

William avoids her glance, looking at his shoes, the wall behind her, her ear.

“Please tell me about your decision to write on the wall with red marker.”

“I’m not,” says William. “Why are you always saying that I’m writing on the wall with red marker?”

Lauren says nothing because she can’t think of anything to say. She pretends to herself that this is a strategy and holds William’s gaze. She thinks about Danny, Danny’s profile picture, Danny someday lightly cupping one of her breasts. William stabs the wall with the marker, smooshing the tip. Red ink runs down the cinderblock. Just then, Lauren’s phone buzzes in her pocket, giving her a jolt of adrenaline. She sneaks a little peek. It’s Danny. He’s sent a shadowy but high-resolution picture of his little pink dick. Lauren stuffs the phone back into her pocket and walks William to his appointment. She rubs his shoulder guiltily as he relaxes down in the cushioned chair. Children never get to sit in comfortable chairs, Lauren thinks, and here she is, always taking it for granted. These one-on-one appointments are her only breaks, so she leaves him with the social worker and rushes into the nearest faculty bathroom. She does not have to pee, but she pulls down her pants and sits on the toilet anyways.

On the toilet, Lauren:

1. Looks more closely at the picture of Danny’s penis, specifically at the dark hair on his white thighs. The hairs are longer than she would have imagined.

2. Asks herself: do I want this penis inside my vagina? Answer: not really, but sure, why not?

3. Feels tempted to post the picture. A caption comes immediately. Every choice that you have made in your life has led you to this exact moment.

4. Posts an image of a sunset behind mountains using the same caption.

5. Replies to Danny. “Wow! Thank you!”

Things have started. She should feel like things have started. Instead, she feels separated from herself. If she were a snail, she would be the shell and the wet slug body, but never both at the same time. There is an impossible rift in her, an enormous gap, and her consciousness must live either muffled from the outside world in her sad, slimy, middle, or in her brittle outer layer, tensed against the battering salt tides.

Danny says You like nature, right? Which means that he’s looking at her feed.

Lauren, naked butt against the now warm porcelain, says yes, she does love nature. Danny proposes a walk around a quiet lake in the town north of theirs. Lauren accepts. Someone knocks on the bathroom door.

“Be right out!” Lauren sing-songs, voice ringing with polite cheer.

◆

The Chore Chart

The Chore Chart is made up of four columns of household tasks, plus each of their names—Mom, Dad, Maggie, and Myrtle—hand-written on a magnet. Their father used to rotate each magnet one column to the right every Sunday evening while Maggie and Myrtle twirled around nearby in nightgowns and bare feet. Like most endings, the end of the Willard family chore rotation was neither abrupt nor very noticeable. Schedules had been shifting for a while, responsibilities delegated differently. Maggie and Myrtle were teenagers. Piece by microscopic piece, their lives were growing separate from those of their parents. The family unit dissolved without ceremony.

Decades after he stopped rotating the magnets, Maggie and Myrtle’s father died a normal, timely death. When their mother followed in a similar fashion, Maggie got the farmhouse because Myrtle was in California, where she’d moved after she’d married Ike and stayed after their divorce. The chart remained on the fridge behind lists, invitations, and photographs.

◆

One Last Thing About Potatoes

Whenever Maggie and Myrtle’s Mom made mashed potatoes, she always smashed in a block of Neufchatel cheese, ruining both girls for any healthier version of the starch.

◆

The Estate Sale

After the last dumpster is carried away, Maggie and Myrtle (but mostly Maggie) hire an expert, a sleek woman in her thirties named Keisha, to come up from Boston and run things. Keisha sets the farmhouse up like an antiques store. Everything visible is for sale: the flatware laid out on the dining room table, the table underneath the flatware, the house that contains it all. “You’re my first living clients!” Keisha tells them. Maggie and Myrtle put clothes and other small personal items they plan to keep in suitcases in the attic. There will be two days in a row of people walking through, buying their family’s things. Keisha has notified dealers and collectors, she’s put up advertisements in all the right places, so people come.

◆

Saturday:

People wander into Maggie’s home, lift things with appraisal and put them back down. Dealers drive up with U-Haul trailers hitched to their car, haggle with Keisha, then drive away with a jumble of artifacts from their family’s history. As they museum-walk through, people dream aloud about what they’d do with the home, the things they would change. Myrtle waltzes around charming potential buyers with stories from their quaint childhood in the farmhouse. This is where they played with their ragdolls. This is where their father chopped the wood. The stories are probably lies—Maggie doesn’t remember most—but they work. People take the flyers. Maggie stands in the kitchen, gripping the back of a chair and trying to breathe. The crew carrying out their grandfather’s wingback knocks it against the door, cracking the foot of the chair.

“You okay?” Maggie asks Myrtle when the last person has gone. “That was intense.”

“Mom always gave the impression that these antiques were worth a lot more, didn’t she?” says Myrtle. “They were always setting us up with these unrealistic expectations. Even now, from beyond the grave. If I could change anything about our family, I would change that.”

Maggie wishes a lot of things were different in their family. She wishes Myrtle had stayed. She wishes the clan had grown instead of shrunk. There should be partners, children, the partners of children, maybe even a grandkid by now. Families are supposed to grow and branch out, not shrivel up and die like theirs did.

“What happened to the money from your divorce?” asks Maggie, shocking herself.

“I’m sorry?” asks Myrtle.

Maggie waits. “You’re clearly out of money. What did you spend it on?”

“Nothing. I don’t know. Life. Rent. Miscellaneous.”

“What does miscellaneous mean? Do you do drugs?”

Myrtle laughs. And Maggie, always the younger sister, can’t help but laugh with her.

“It’s mind-blowing,” says Myrtle. “I don’t even have that nice of a life. Just went out for too many meals, I guess. Maybe a few too many pedicures? Bought hardcover books instead of borrowing from the library?”

◆

Sunday:

Wise from the day before, Maggie makes plans to spend time out during the sale. She meets Kathy at noon at the breakfast diner on Derry’s small, historic main street. She orders a veggie burger. Kathy orders an egg sandwich and home fries.

“This is none of my business,” Kathy says, “but there are a lot of people who love you, Maggie. And we can see certain things. Myrtle’s always come in like a whirlwind. There’s going to be a time—I’m not saying it’s this time—when the pieces don’t fit back together after she’s gone.”

The waiter comes by with refills. As Maggie watches the coffee glug from the carafe into her ceramic mug, she tries to imagine all the people that love her. She can only come up with Kathy and Myrtle. And Myrtle’s awful, dangerous sister love eclipses Kathy’s stupid neighbor love so grandly that Kathy, sitting across the booth with a smear of egg on her concerned face, seems like a complete joke.

“You’re right,” says Maggie. She gives Kathy a big, polite smile.

Back home, there are too many cars at the house for Maggie to park in her own driveway. She parks on the street and walks up to her farmhouse behind a young couple.

Maggie watches the young woman grasp the young man’s arm. She watches them turn to each other and smile. The young woman giggle whispers to the young man and he smooshes her cheek in a kiss. Our house, she sees the young man say to the young woman, though she can’t hear the words from where she’s standing. Instead, she hears the familiar rumble of the ATVs in the woods across the road, the wind through her mother’s chimes.

“Hello,” says Maggie, “I’m the seller.”

“Oh!” says the young woman. “Why would you ever sell this awesome place?”

“I’m moving to Barcelona with my sister.” This time, when she says it, she understands that it was never true.

“Wow!” says the young woman, “How cool! That is so so special!”

And Maggie can see that she really means it. This young woman is impressed. Silly girl believes in the upward trajectory of Maggie’s life. Silly girl believes that Maggie has a sister who isn’t a self-obsessed piece of shit. Maggie takes the couple inside, where Myrtle and Keisha are still hawking off everything of value. She leads them through all of the rooms, no longer her rooms, but already beginning to belong to them as they take it all in, faces shining.

◆

Danny Kills Lauren by the Lake

He’s waiting in his car when she pulls into the gravel lot, looking at his phone. He tucks the phone away quickly when she knocks on his window and steps out of his car. He’s put effort into his appearance, tucking in his flannel shirt and combing his hair back off his face.

“Shall we?” Lauren says, gesturing toward the muddy trail around the lake. Danny nods.

“You look really nice,” he says. “I like your boots.”

“Thanks,” Lauren says. She lifts her foot and twists her ankle around to display the boot from all angles. “It’s hard to find boots that are both practical and attractive.”

They start down the trail. Late winter is Lauren’s least favorite time of year. The trees all naked, the lake gray. On the right side of the trail, big boulders stand between the trees and the lake. They reach a place where the trail opens to a concrete foundation half-submerged. Lauren can hear the road, but she can’t see it.

“Want to stop here for a bit?” Lauren asks.

“Sure,” says Danny, “this concrete thing is pretty cool.”

“I’m going to climb on it,” says Lauren, but then she doesn’t. The waves lap at the shore.

“Do you need a boost?” Danny asks.

There’s something wrong with his voice. A dreadful understanding rushes through Lauren’s body. Oh. Oh no. But also, Wow, really? Wow, me?

“A boost,” Lauren repeats, giggling.

“What?” asks Danny.

Lauren keeps giggling. She can’t stop. She’s feeling lightheaded, like she might pee, but also like she’ll maybe never pee again.

“What are you laughing at?” asks Danny. “It’s called a boost. That’s what it’s called.”

Lauren puts her hand over her mouth. She manages to calm herself down.

“I’m not laughing at you,” says Lauren.

Danny puts his hand over the front pocket of his pants. He turns and vomits into the lake.

Lauren watches his seizing back. She’d thought he was thin, but this position makes his sides bulge. Finished, Danny blows the vomit from his nostrils one by one. He’s crying. He’s taking a hunting knife from his pocket.

Run. Her mother’s voice, somehow.

Lauren’s feet are cold, the boots inadequate after all. On top of the difficulty of finding boots that keep your feet warm and safe while looking good, the stores always display ridiculously small samples. Once you find your normal size in the jumbled boxes below, you’re inevitably disappointed by how bulky they look. And, even if you manage to find a boot you like at the store, even if you’re able to check out without being overcome by regret, there will be a moment when you’re walking down the street or scrolling through your feed when you see another woman in another boot and realize something humiliating about the boots that you have purchased, how, in choosing them, you’ve inadvertently advertised some great internal lack to the world. It is so hard to have the right things. Hard, but possible. Though not for Lauren, anymore.

Danny’s grip on the hunting knife is wobbly. She could knock it out. She could also kiss him. She is a woman completely in charge of her body, and she could do anything that she wants right now. It begins to snow.

“You didn’t kill the other girl though,” Lauren says.

Briefly, in the summer between high school and college, Lauren caught a boyfriend in an inconsequential lie. Now, she no longer remembers the lie, but she does remember the gratitude that spread over his face when she called him out. How wonderful for the human heart to find itself known.

First, Danny stabs her in the arm. Being stabbed in the arm feels exactly how she expects it to feel: it’s awful, it’s the worst thing. This is not a game. Now, Lauren tries to run. But she trips. Lands on the wet forest ground. The snow is melting as it lands and water beads on all the pine needles that aren’t half-decomposed. Face on the ground, Lauren sees all this from up close. The forest floor smells like spring. Danny stands over her, a foot at each hip, and pushes the knife into the side of her neck. Lauren has no time to consider what it’s like to be killed, it simply happens.

◆

An Empty House is Full of Potential

Maggie tiptoes through the empty rooms. Her footsteps echo off the freshly painted walls and the waxed floors reflect the afternoon sun. Without her things, she feels great. Youthful, buoyant, ready to take on the world. Myrtle was right, she thinks. After all that.

They have 30 days to figure out their living situation before the young couple needs them out of the farmhouse. Barcelona is crazy of course—but what about South Carolina? Florida? Arizona? Maggie finds Myrtle, who’s sitting in a camp chair in the empty sunroom. Dread seeps in around the edges. Maggie pushes it away.

“Myrtle?” Maggie says, everything clenched.

Myrtle looks up from her phone. “The W.H.O. just classified it as a pandemic,” she says. “I think travel is probably going to get messed up. I’m sorry, I know I said I’d stay and help you get settled into a new place, but people are going to be stuck wherever they are soon. I have to get home.”

The sisters look at one another in silence.

“Don’t look at me like that,” says Myrtle. “This is out of my control.”

“Help me get settled?” Maggie finally says.

“There are some really clean apartments for lease near the center of town. I’ll send you some links.”

“Alone,” says Maggie.

“Right,” says Myrtle. “What?”

“Why don’t you just stay here?”

“Maggie, I’ve lived in Los Angeles for almost thirty years. There’s nothing here for me.”

“I’m here.”

“That’s not what I meant.”

A red-shouldered hawk lands on the birch outside the window behind Myrtle. Maggie remembers a trip she took in her late teens to visit her older sister, who was living somewhere flat and awful in the middle of the country because of some boyfriend, a few men before Ike. The boyfriend sent them out on a hike while he worked. Growing up in New Hampshire, Myrtle and Maggie had hiked quite a bit, and it was their habit to save their sandwiches for when they reached the peak of the mountain. But there’d been no peak on this midwestern hike, just a long trail that wound around a sad hilly area near a swampy creak. Myrtle and Maggie had finished the hike starving, their sandwiches warm and mushy in their backpacks.

“Stop biting your nails,” Myrtle says. “It’s disgusting.”

Maggie takes her fingers out of her mouth and studies them before looking up at Myrtle. “You won’t get your half for months,” Maggie says.

“What?”

“The money from the house.”

“Okay. I don’t know what that has to do with this.”

“You came here for the money.”

“Maggie, you were living in swill. This was an intervention. The last time I came the house was infested with bugs.”

The hawk lifts up one of his talons and begins to chew at it.

“You got bit by some mosquitos one night, so you came back four years later to fix me? You’re a real hero, Myrtle.”

“It wasn’t four years,” says Myrtle.

“It was.”

The hawk flies off, leaving the birch shaking in its wake.

“I’m leaving in the morning,” says Myrtle. “I need to go upstairs and pack.”

Myrtle stays in her room with the door closed through dinner time. Maggie spends most of this time in her own room, laying on the mattress, which is now on the floor, scrolling through the news. She can hear Myrtle whispering into her phone every so often. Because she’s afraid to knock, Maggie sends her sister a text.

What time is your flight?

8:30.

I’ll drive you.

It’s okay. I already scheduled a car.

Myrtle emerges from her room.

“Are you going to be okay?” she asks.

Maggie shrugs.

“I mean with the virus,” says Myrtle.

“You said you wanted to live with me.”

“What?” says Myrtle. “I’m sorry, but I don’t think I ever said that. It does sound nice, though. I wish we could live together.”

“Why can’t we?”

“I have to go home.”

◆

Sleeping Arrangements

Maggie goes to sleep on her own mattress but wakes up panicked in the middle of the night. She tiptoes over to Myrtle’s room and eases open the door. Myrtle has pushed her mattress into the far corner of the room. Maggie squints against the dark. Her sister is a lump beneath a grey afghan. The lump rises and falls with each slow breath.

“Myrtle,” Maggie whispers. “Can I sleep in here with you?”

Myrtle groans in the dark. “I guess so,” she says. She lifts the afghan so that Maggie can crawl onto the mattress beside her, tucks it tight around Maggie’s shoulders, and then drifts back to sleep.

◆

Lauren’s Body

A woman walking her two Dalmatians around the lake finds Lauren’s body. The knife waits browning on the ground nearby and Lauren’s phone, full of DMs from Danny about this date, rests in Lauren’s cold pocket. Danny is arrested. Though the ear and the finger could not have possibly belonged to Lauren, though the details of those crimes do not necessarily point to Danny, complacency falls. There is the other thing now, and the human heart can only hold so much worry. Spring comes. The crocuses push up.