For most of his life, Charlie had disbelieved in everything. He had never been religious, nor given into any sort of magical thinking. He did not believe in luck, signs, or supernatural abilities. He’d always been against the spreading of this type of thinking to children through the folklore of the Easter Bunny, Tooth Fairy or Santa Claus. He found no entertainment in scary movies or haunted houses, and scoffed when a friend showed him pictures on her phone of “ghosts” (reflected water droplets in the air, he’d told her) when they were in New Orleans. When Charlie met his wife, Amanda, they shared this: logic, reason, pragmatism.

Charlie was a preschool teacher, a job generally reserved for women, but given to Charlie for the way kids seemed to calm around him and because—though they’d never admit it—his employers thought he was gay. Since Charlie never felt the need to declare himself one way or another (despite having only been with women), he said nothing when he overheard his coworkers talk about how sad it was that he hadn’t come out. “That poor wife of his,” one had said. “He’s probably afraid of what his family will think,” said another. Charlie had also not told his coworkers that he had no family, that both of his parents had died two years ago on their 60th wedding anniversary. They jumped off a cruise ship—not suicidally, but because they were feeling spontaneous and young again. The water had been colder than imagined and the rescue team inadequate. All of this Charlie kept to himself.

On a day when Charlie wasn’t thinking about any of that and was actually feeling quite light, one of his students said something that shook it all up again. It was Ollie, an odd-looking, but striking four-year-old girl with big, dark eyes and a furrowed brow. She approached Charlie on the playground, pointed to an empty corner by the fence and said, “I saw your mommy over dere.” At first, Charlie just played along and said, “Oh yeah, what did she look like?” But Ollie hadn’t gotten shy or nervous the way most kids do when making something up. She just said, “She’s got curly lellow hair, a big nose, and a brown polka dot above her lip.” All of it had been true, and it made Charlie feel sick.

This wouldn’t have affected him as much coming from a different child, but Ollie seemed to be in touch with an otherworldliness. It was evident in the way she danced around the nap room like some broken ballerina to the ethereal music Charlie played from his phone. “Dis is my favorite song,” she’d say about a track called Deep Sea Sounds, twirling slowly in an alien, all-elbows kind of way. And sometimes she’d just stare into the middle distance, while Charlie read a storybook, and say some ominous shit like, “Dey’re coming.” There was something in the way she looked—frizzy hair framing her head like a halo, bright frightened eyes—that made Charlie believe her.

◆

Amanda didn’t want children. This used to be something she and Charlie agreed on, but the more time Charlie spent with kids, the more he felt that changing. Sometimes he imagined what it would be like if Ollie were his own child. He imagined taking her to the grocery store, lifting her up on his shoulders to grab cereal boxes from the top shelf. He’d be able to say, This is my child. Isn’t she odd? Isn’t she wonderful? Because the truth was Charlie loved Ollie. Loving the troubled ones was easy. He’d never felt an affection for the kids who wore appropriately holiday-themed clothing or had well-balanced lunch boxes, the kids who used the word quinoa when they played house. No, he preferred the ones with an edge and depth, like the boy named Jade who would throw his water bottle across the room when it got too loud, or a girl named Venice who’d roll herself in dirt just before nap so Charlie would have to clean her up for half the allotted sleeping time. It was these difficult ones Charlie fell for. Especially those whose parents seemed ill-fitted for the job. Ollie’s parents were among these. Her dad, he could tell, was a man who spent most of his time in a dim room playing computer games; he always wore a t-shirt tucked into belted jeans, big white tennis shoes, and a black patch-work leather jacket no matter the weather. Her mother was a woman-child or child-woman, her face pale and round, her hair always in pigtails like a bigger (but not grown-up) version of Ollie. She’d slap her palms together at pick-up time, shouting, “O-llie! O-llie!” in a sing-songy voice, the way a toddler might call a dog. For all of these reasons and more, Charlie felt a certain obligation to Ollie: to listen to her, take care of her, to believe her. The lattermost obligation just happen to be fucking him up.

When Charlie started telling Amanda about Ollie, she said things like, “You’re not well, Charlie. And that child doesn’t seem well either.” Or “I’m concerned that you’re getting spooked by the nonsense of some demented four-year old.”

“She is not demented,” Charlie had said, slamming the fridge door. The next morning when he opened it, three bottles of beer fell out and broke.

◆

Then a couple weeks ago, Ollie woke up from a nap and said, “Charlie, I don’t get it.”

“Get what?” Charlie had said, helping her fold her Cinderella blanket.

“The ghosts,” she said, looking at him, blinking twice. “Why are dey here?”

“There are no ghosts, Ollie,” Charlie said, patting her head, and sending her off to the playground. But he did not stay behind to do his usual wipe down of the mats, and instead followed Ollie outside, glancing around the room behind him as he shut the door.

This continued for days: The ghosts are in the parkin lot; The ghosts are in my house.

Finally, thinking he might use some amateur psychology, Charlie asked, “Where do the ghosts come from, Ollie?”

“The ghosts come from the bad news,” she said matter-of-factly.

“What kind of bad news?” he said.

“You have the bad news,” she said

“No, I don’t,” Charlie said, trying to force a smile. “I don’t have any bad news, Ollie. Only good.”

“Tomorrow…” she said, looking up at the sky.

“What about tomorrow?” Charlie asked.

“Tomorrow, I’m getting a dollhouse!” she said and ran off.

That night, while Charlie showered and steam filled the bathroom, Amanda stood on the other side of the curtain and told him she no longer loved him. Charlie hadn’t heard Amanda. He was distracted—thinking of Ollie’s visions, wondering if she really had seen his mother. So, sometime later he called out, “Wait, what did you say?” But by then, she’d already left the bathroom, and was in their bed asleep. He didn’t have to ask again, because a week later she was gone.

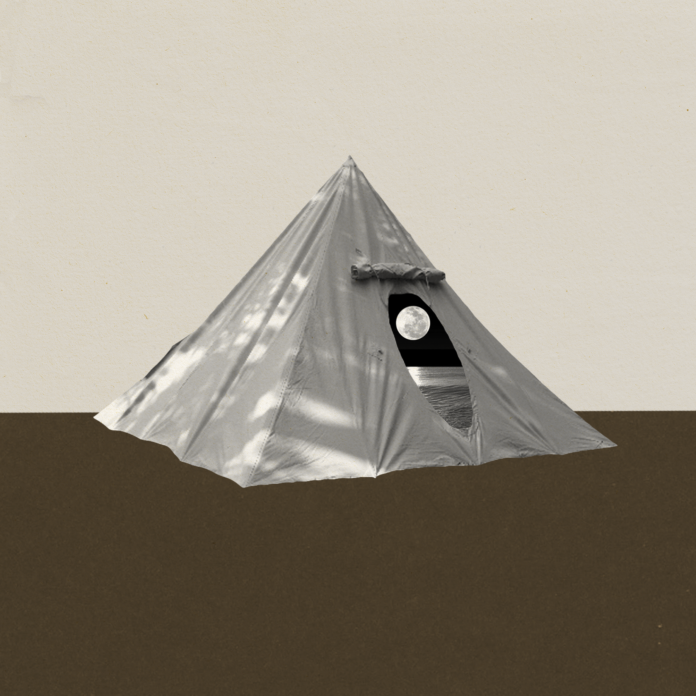

After Amanda left, Charlie felt how he imagined the kids at work must feel during naptime: the people they love the most have left them to be led into a dark room expected to sleep. They are exhausted and longing, but afraid of closing their eyes. And even when they sleep, they whisper mama in their dreams. Charlie would sometimes pat their backs or smooth their hair back until their worried foreheads relaxed and they finally fell into slumber, but there was no one here to do that for Charlie. So after a fitful night of sleep, Charlie woke at the first glimmer of dawn, and went camping.

Though he didn’t consider himself outdoorsy and had never bought any cool camping gadgets, Charlie liked the simplicity of going to sleep when it got dark and waking to the sun and sound of birds. On the drive down to Lost Oak State Park, he’d heard on the radio about a county-wide treasure hunt. The first clue was for Lost Oak! “Whatever is so round, is so blue, underneath which, you find you.” Charlie had never been very good at riddles or clues. They were like poetry to him; he liked them, liked to think about them, but they could mean anything.

At the trailhead, Charlie parked beside a young couple. He watched them as they got out of their hatchback, and pulled on over-sized backpacks. Hatchback. Backpacks, Charlie thought. The girl had colorful outdoor clothing and a long, wavy ponytail. The boy wore a headlamp, though it was the middle of the day, and carried a gallon of water in each hand. He looked like anyone too prepared: ridiculous. Charlie waited until they were out of sight before getting out of his car and pulling on his own backpack, in which he’d packed a towel, a bottle of water, nuts, crackers, and a can of sardines. The bare minimum.

He stopped in front of the park’s map in a mall-like display, tracing a path with his finger from You Are Here to Pebble Falls.

As he climbed the hill, he said to himself, “Take a hike.” Which is what Amanda used to say when she didn’t believe something. Instead of no way, or get out of dodge, she would say, Take. A. Hike. Charlie said it like this, in time with the beat of his tan canvas shoes against the gravel as he went up, up, up: take-a-hike, take-a-hike.

When Charlie reached the top of the hill, he was sweating through his t-shirt. He didn’t feel very afraid or sad. Good.

He got out his water bottle, which was hot now, but chugged it anyway, sucking until the plastic crinkled inward. Ahead of him, he could hear that couple laughing. Charlie wanted to be laughing with someone. He picked up a blue flower from the ground, held it in his fingers, rubbed his thumb along the soft petals, then pushed it into the empty bottle and threw it in his backpack. Maybe it wasn’t the treasure, but it was a treasure. …underneath which, you find you. He wondered if he could find himself in a flower. He supposed he could. He sat and listened to the sounds around him: leaves rustling, birds chirping, and in the distance, a waterfall. Then he stood and started climbing again, but after only a few more turns, he stepped through some brush and there it was, flowing into a natural pool, looking more exotic than he imagined.

Were ghosts in places like this? he wondered. Amanda would not have liked a question like that. While he’d been asking her things like, do you think ghosts get thirsty or would she take a picture on her phone of that corner of the bedroom, she was telling him she was tired of comforting him, that maybe she wanted to be comforted. And though it was true that lately he’d been easily creeped out on their night walks—startled by the cats that leapt out of bushes—he felt that otherwise, he was pretty brave. He tried to tell her this one night and she’d said, “You can’t tell someone you’re brave, Charlie. It’s something you just are without having to say it.” Then she’d rolled over.

Charlie looked at the waterfall—small and pleasant, like the kind they tried to emulate in fancy hotels. He watched the trees sway. The round leaves flickered in the wind like glitter. A leaf fell. A stick moved. A bird flew off a branch. Things just kept on moving, didn’t they? He wished they would slow down. He wanted time to stop like it did in movies. He wanted to walk down the street and see a tossed coin, frozen in the air. Touch a kid’s gum bubble mid-blow. He wanted that tiny bird to stop its quick wings right in front of him so he could pet its little head; he wanted to go around running through these woods, yelling and screaming like a man who was free of it all.

He stood up and pulled off his shirt, looked down at his body, and slapped his thick stomach. It could be worse, he supposed. He walked toward the water, stepping in slowly, letting the cold water rise gradually up his body, the way he did when he was a child and his dad had called him a pansy-ass, pushing him into the pool. But his dad had never understood that it wasn’t because he was afraid of the cold; it was the opposite, rather. He liked to feel it creep up on him. The water rose near his groin and he felt a reflex, pulling up, his body trying to protect itself from the inevitable. Once above his chest, he submerged himself completely, letting the cold water rush over his head.

People thought, because of what happened to his parents, he wouldn’t enjoy swimming. But the story of his parents’ death felt like an old memory that wasn’t his. Like a sad story he’d heard secondhand. Or, that’s how it used to feel. It felt now like something was breaking open, something foundational was shifting inside of Charlie. He knew, but not yet how, that this had to do with Ollie, with her ghosts.

Charlie swam like a frog pushing out his legs. Whatever is so round is so blue. Maybe there was a treasure down here. He skimmed the bottom of the pond with his feet. He opened his eyes underwater, but could only see blurry rocks. Oh well. Then because he felt like it, he pulled off his shorts, surfaced, and threw them onto a rock. He kept swimming. Why can’t I just do this forever? he thought. If I could, I would. I surely would. This last part he sang in his brain like that Simon & Garfunkel song: I’d rather be a hammer than a nail. Yes I would. If I could, I surely wo-o-uld. Charlie figured he was probably a nail. Nothing he could do about it.

He got out and lay down on the rock to dry. He pulled a ziplock bag of peanuts from his backpack and poured them into his mouth. He put his shirt back on. His shorts were still wet, so he hung them on a branch. Charlie sat there pantless, and hoped no one would see him. But then again, so what? This was him, this was his body. We’re all human, aren’t we? But we aren’t, so when he thought he heard someone, he grabbed his cold wet shorts, pulled them on and walked away.

Further up the trail, he came upon a hammock tied between two trees. It was full of leaves. He dumped them out and lay in it. And as the sky faded into a darker shade of blue, he closed his eyes and thought of his and Amanda’s first kiss. It had been in the backyard of some bed and breakfast in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Amanda had asked him to be her date to a wedding the first night they met. They’d been talking at a party, and being as direct as ever, Amanda had said, “Hey. Wanna drive to a wedding with me tomorrow?” After the reception, they snuck around the old house, collapsed in a hammock and kissed.

◆

Charlie opened his eyes. In the distance, he could hear the panting sounds of sex, which always both embarrassed and aroused him. He climbed out of the hammock and kept walking, but soon realized he was walking toward the sound. Through the trees he saw a rocking tent, outside of which were the jugs of water. Of course that lovey dovey couple was doing it. He turned around, but as he walked away, he wondered, despite himself, what their lives were like; if one of them was more afraid than the other, or sadder, if one loved the other one more. Or if maybe that’s how it always was. It made him anxious to think about all these people living lives as complex as his. This feeling was called something, he was pretty sure. It had a name, he’d seen it on one of those lists of words that can’t be translated. It might have been German or Japanese, but he couldn’t remember. Suddenly, a cold breeze blew through him. He crossed his arms and shivered.

Charlie looked at the ground and kicked around some leaves. He still hadn’t seen anything that looked like a treasure. He wanted to find whatever it was and bring it to Ollie. Show her there were beautiful things in this world, things to look for and be found. He decided he would go ahead and eat dinner: a can of anchovies and saltines, sleep in his car, and do a real search in the morning.

On the way back down to the parking lot, Charlie noticed some bones—a rib cage from something large, like a bear—on the side of the trail. This made him think of his mother, who used to collect bones. She kept them on windowsills and propped up in the garden. Her favorite was a windchime—a hanging collection of hollowed-out femurs—that hung outside their kitchen window. The sound of bones knocking against each other had always made Charlie’s teeth clench. He did not like to think about what the inside of his body was made up of, much less did he want those things clattering in the breeze with an intention of putting him at ease. His mother would say, reaching her hand out the window to touch it, “Isn’t it wonderful how things can go on making music, even after they’re dead?” But Charlie did not think it was wonderful. He’d prefer the end to go ahead and be the end. Still, even though his parents’ bodies had been retrieved and buried, he sometimes imagined his mother’s bones at the bottom of the ocean making music like Ollie’s favorite song: spectral and cetaceous.

Charlie heard running behind him. He turned around, readying himself to crouch or jump out of the way of a bear or bobcat, but it was just the lovey dovey boy. He was out of breath and his eyes were wild.

“Excuse me sir,” he yelled, waving his arms like Charlie might not see him, “Do you have a phone?”

Charlie pulled his phone from his backpack and waved it at him.

When the guy reached him he said, “Can you dial 911? We don’t have our phones and my girlfriend is passed out, and I don’t know why.”

Charlie had never dialed 911 before. Even as he tapped the numbers now, he felt like it was happening by accident. When he looked up, the guy was running away. The operator answered, and Charlie gave her what little information he had. They said they were coming, so he hung up. Then Charlie just stood there on the trail, not knowing what to do next. He walked slowly in the direction the boy had gone, but then stopped and turned around. If he tried to find the couple, and the girl wasn’t okay, what could he do? And if she was fine? He wouldn’t be needed. If he were with Amanda, she’d say don’t worry about it; it’s none of your business. But then again, he wasn’t with Amanda, so he turned around and ran after the boy. “Hey!” he called out to him, “Hey!”

When Charlie finally caught up to him, they were back at the tent. The girl was sitting up, drinking water from one of the big gallons.

“Oh my god,” the boy said. “You’re okay.”

“Why did you leave me?” she said, taking another gulp of water.

“I went to get help,” the boy said, pointing over his shoulder and then looking behind him, jumping a little, surprised to see Charlie.

Charlie waved.

The girl shook her head. “Jesus, Derek. I was just dehydrated,” she said. “I’m fine.”

“Welp,” Charlie said, clasping his hands in front of him, “I’m glad to see everyone is okay.” And then when neither of them responded, he said, “Goodnight!” and walked away.

◆

So the girl was fine. But she might not have been. And ya know what? Charlie would have been there. This he felt good about.

It was getting dark. The surrounding trees shaped the sky into a dark blue oval; stars were all over the place. Again, it looked fake, like the ceiling of an observatory he and Amanda once visited in Chicago. They’d smoked weed in the park beforehand, and walked along the edge of Lake Michigan to a circular building on the end of a small peninsula. He remembered not being able to distinguish the two blues of the water and sky. It had been one of the most beautiful things he’d ever seen.

He thought of the boy’s wild eyes, how afraid he’d been that he’d lost her. Charlie knew that feeling. Amanda might not have been dead, but he had definitely lost her. He used to think if he got better, he could win her back. But Charlie was starting to think that maybe, in a different way, he was better.

When he got to his car, he turned on the interior lights and did a quick look-over. He locked the doors, rolled a sweater up for a pillow, and lay down in the backseat, covering himself with his “emergency blanket”—a tapestried thing he was proud to always keep in his car. See, he had not lost all his pragmatism. That part, he knew, would serve him well as a father. Yes, Charlie thought, pressing his feet against the cold of the car door, he would have a child. He closed his eyes and fell asleep to thoughts of babies, and then ghosts, and then of trees and bones.

◆

When he awoke, the sun was just beginning to rise above the pines. His back hurt, but otherwise he felt okay. He walked toward the trees to pee, and saw something flicker in the grass. It was a small, blue hand-mirror. He picked it up and looked at himself. His eyes were gray. Underneath the mirror was an envelope that read: You found it! CLUE #2! He opened it. See it lies in the swing, rustling around, a special thing. There must have been something in the hammock! But Charlie didn’t feel like going back. So much had happened, or at least it felt that way. So he pocketed the mirror; Ollie would like it.

He got back in his car, and looked over at the lovers’ hatchback. He thought about leaving them a note, but wasn’t sure what he’d say. So he thought a good thought and blew a kiss toward their car. Then he shook his head and laughed at himself.

As he left the campsite and drove down the twisting dirt road, Charlie thought he saw something, someone in the rear-view mirror. He got a strong, strange feeling that someone was in the backseat. But he wasn’t scared. Charlie just shrugged his shoulders and kept on driving. He turned on the radio and found the classical station. He wondered if ghosts liked music. He turned it up, just in case.

“I don’t know, Ollie,” he said out loud. “I don’t know why they’re here, but here we all are.”