Oftentimes, my room is called the “black hole” in my household because of all the many things that are suddenly and unexpectedly lost to it. But loss does not remain only within those four confiningly white walls; it follows me. An absentminded klutz no more deft than a clod of dirt, I lose things that aren’t even mine to lose. I’ve normalized loss to the point that it’s become my defining characteristic. Routinely, I misplace my keys right before work or my wallet just before I need to hop on the bus and run to class. You’d think my heart would learn to stop dropping when I reach for an empty pocket expectantly. You’d think I’d learn to be more careful. If anyone thought that then they couldn’t be more wrong because here I am scrambling through piles of dirty clothes, old sketchbooks and diaries, crisps of leaves from last fall, and loaned-out library books like the drowned gasp for another breath of air.

Oh god… I can’t find it!

◆

Redwoods in the winter have a somber nature about them, especially when it rains as it did that day. It poured all through the previous night and well into the afternoon. I remember waking to dismal, gray skies, overcast and downtrodden. On those kinds of rainy days, I had to tuck all my hair into my Oaklandish beanie to keep it from reverting and ruining the effort of hours spent early each morning straightening my frizzy brown hair into submission. Anything to keep from looking unkempt, but the rain has always been my joy so I didn’t flinch and duck away from it the way others did. I looked up directly at the sky, inviting the wet kisses of raindrops across my face as if I were leaning into a friend’s melancholy, my arm around her shoulders. I indulged.

There was the muddy footfall of obscure hooded figures, tree leaves chattering, petrichor in the air, water rushing to get anywhere fast, and tree trunks creaking as they yielded to wind. Normally, I’d scurry around campus in a caffeinated daze but when it rains, I linger… and stall… and savor the wasted time over a hot cup of chamomile tea. Mills is certainly expensive but at least it’s damn pretty.

For a few moments, I had the redwoods to myself. Huge, floor-to-ceiling length windows perfectly captured the climbing sagacity of these trees who mysteriously survived by drinking the mist rather than waiting on California’s sparse and infrequent rains to eventually kill them. Nothing could live as long as a redwood. In awe and envy, I gazed at them from a cubicle-like study bench on the indoor balcony of the F. W. Olin Library. In front of me were a variety of poetry anthologies—some in Spanish, English, or both—and my cell phone with the ringer off as well as a notebook I barely started writing in, all of which I neglected. Lost in the pitter patter of the rain on the skylight, a warm, callused hand cupped my thigh making me jump. Then, a coffee and cigarette stained voice whispered close to my face.

“¿Donde ha estado, morenita?”

“Right here, honey,” I whispered back, a little relieved, but not much.

“What’re you doing?”

“Studying. Reading poetry.”

“That’s good. Did you still want to get something to eat?”

His face showed no sign of interest in the material but he wasn’t the literary type. While I was finishing my 2nd year at a private women’s college dedicated to social justice and progressive change, he had been taking mechanic classes at the local community college. That is, when he wasn’t being reprimanded for violating the student code of conduct. Surely his interests would take him somewhere, but I wasn’t convinced that he had many realistic ambitions because he wasn’t convinced either. It was still January and he was already suspended for the Spring 2018 semester over some altercation with a campus security guard finding weed in his car. He waited awkwardly with one foot in my study corner and one foot out, his mess of black curls just peeking from behind the wall enclosing the bench.

His eyes were always his most intimidating feature until I had seen him in slumber where the thick veil of black lashes softened his tough face. After these past four years of watching him do the only thing he could do peacefully, that is sleep, I could just about read him from eye contact alone. Right then, those eyes were telling me he had been patient long enough. I’m sure that I had him waiting on me for a while. Sometimes he could be kind and gentle, like he was trying to be in that moment (as he’s not known for his patience). But, most of the time he’s going on, shouting and stamping about something or other, endangering the safety of everyone around him in his fits of rage. I’d heard stories about how he threw his five-year-old sister into the wall or pushed his older sister to the floor while in her third trimester. No one ever could tell me exactly why.

Just then, the blinding heat in my pelvis was telling me to hurry up and get in this reckless man’s car.

“Yea. Let’s see what’s good in the East today.”

◆

– Monday, May 7, 2018 –

Hey ugly

Hey

Trying to find the sonogram

Do you remember where I put it?

I love you morenita and idk where you put it

I need it

Do I make you happy?

It’s not a good time to ask me that

I think I’m mourning

Did you find the sonogram?

No.

◆

Flipping through the pages of every sentimental book I own, they waft the familiar and normally comforting scent of paper and ink, all earthy and marzipan-like, into my glowing, tear-streaked cheeks. Unceremoniously, I unshelve Stephenie Meyer and Jane Austen from my homemade bookshelf (made from old cardboard boxes and hot glue) to no avail.

Where the fuck did I put it?

I check the manila folder containing my medical records, my precious childhood memory boxes, even my not-so-secret vibrator drawer with the wire running from it in plain sight. There, I found a clue. The pregnancy test still showed the positive symbol for yes, you need $500 dollars and a ride to the clinic.

I was so grateful that I had health insurance that year or else the bill would’ve been higher, grateful that I had a mother that didn’t kick me out when I told her. Even more grateful still that I would never need to have this conversation with my very hot-headed and very dead father. In conflict with my morbid gratitude was this unexpected feeling of rising excitement like the first crackles and pops of a newborn campfire. I was ashamed to admit it and wouldn’t know who to admit it to but… I was thrilled, elated even, for the new changes in my body that though painful I knew connected me to the new life in my womb and the man who helped create it.

I was 20 years old and pregnant. Ambitious, in love, and on food stamps. Despite my circumstances, when I first saw that positive symbol it actually felt like a blessing.

A blessed brown baby.

It should have been as simple as that.

I believed without really knowing (because it was too early to tell) that she was my little girl. My Rosita. Rosabella Marie Muhammad. Beautiful rose and praised star of the sea. I gave her life, if only, in name.

Early on, I resolved not to take the name of my husband, at least not to drop my father’s spiritual last name. It is the only remnant I have of him anymore, accompanied by some fast fading childhood memories.

Raul and I both have last names that we only share with our fathers and not with any of our siblings, but Raul’s father chose to abandon his son and family. A decision that I could not understand and could only pity Raul’s family for. Raul couldn’t care less about his last name and so conceded to my condition, but only hypothetically since we were still a bit too young to marry. While I idolized my father, he resented his own.

Everything he said to me was a kind of a lie, especially when he found out that I was pregnant. Afterall, he couldn’t very well drop the manipulation tactics right at the most pivotal moment when the cards were in my hands, which he loathed bitterly. He had done things like called me a “loser,” “ugly,” and other names then acted like those were terms of endearment when I told him I felt otherwise; spent the night at his girl best friend’s house then invalidated any reasonable concerns I had about the situation; accused me of being too flirtatious for enjoying flattery from another guy when his idea of romance was strictly limited to sexual performances he coerced me into and managed to make intolerably stressful. He regarded my pleasure only insofar as it amplified his own. It became evident to me only now that, as a Black woman, he thought and treated me as a sexual object.

His undiagnosed, untreated emotional disorder and my own were like two passively volatile substances creating a dangerously explosive chemical reaction when in romantic proximity. Every day I spent with him was more and more reason to pity that miserable soul, but not more than I pitied my own child, who I alone would recognize as a gift, even if I shouldn’t.

◆

Cuando Me Despierto

No podría vivir sin tus pestañas

barriendo a través de mi rostro

por la luz de la madrugada o

las melodías brillantes de medianoche.

Tu respiración sola esta encantadora a mi,

dulce como la fragancia de la vida misma.

Tu pelo como los movimientos mas internos de la mar

baile, igualmente tan oscuro y juguetón,

rizos de un espíritu libre.

Con confiaz tan frágil

tu piel recibe mis caricias

y siento aprensión inmensa

porque, ¿Qué aguarda el futuro?

Te necesito más que cualquier cosa.

Más que agua o comida, amparo o reputación,

más que soledad o compañía,

más que la próxima respiración.

Digo todo esto con mi cuerpo completamente,

la esencia de mi existencia,

la fibra de mi alma.

No hay casa sin tu.

y todavía…

me despierto sola.

◆

I thought her alive.

I wrote her letters in the shape of poems. Vainly, I asked for her forgiveness. I searched for her hybridity in Oakland’s multiracial streets desperate to trace the impression of her existence against my tender memory. What would she look like? How would she smell? Where would her voice fall in between our languages? I obsessed over photos of little sausage-limbed mixed babies, light-skinned and curly headed, of which there are a surprising amount of instagram accounts dedicated to. In Spanish class, I took interest in the history of the blending of Black and Latino cultures. While at the campus library, I picked up a copy of Black in Latin America by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and discovered the plethora of names used to describe Black people in various Central and South American countries.

These are some of the terms used to describe shades of Blackness in Mexico;

Cambujo

Grifo

Cuarterón

Quinteron

Saltatrás

Morisco

Prieta

Zambo

Then there’s the names I’ve been called in Spanish;

Negra

Morena

Mulata

Mayate

I knew about the racial castas system from those 18th century Mexican paintings and the concepts of mestizo, mestizaje, and blanqueamiento from Gloria Anzaldúa and Walter Mignolo. However, I was never quite sure which of these terms I should be grateful or upset to hear. I didn’t know which terms celebrated Blackness, the history and experience of it, or which demonized it, as a thing that prompted name calling and violence. College has enlightened me to the harsh reality and prevalence of racism, but the Bay Area is not as Black as it can sometimes feel and studying at a predominantly white and hispanic institution made me uncomfortable talking about anti-Blackness in the classroom. The kind of anti-Blackness that tied a noose on a tree in front of the Warren Onley resident hall.

One day, during the ten minute break just before my African American’s History class began, an older white woman in my class was venting to me. She was worried about her financial aid not coming through on time and subsequently being automatically dropped from the course. As a working student, I let her know that I understood what it was like to have your education hanging in the balance over an uncertain paycheck. Then she said, “I mean slavery is bad but when you think about how much money they were making,” she raised her eyebrows at me, “I mean anything to pay off this debt.”

I suppose I expected better from Raul’s family, whom I began to think of as in-laws, despite the red flags. But I also am not unlike many other Black people who desperately want lighter-skinned mixed babies with “good” hair. It’s not like miscegenation has ever fixed racism.

A nightmare screamed at me that the perceived “political progress” of my interracial relationship would be overshadowed by my children’s desperation to claw out of their Blackness, to escape and disown it as I have tried.

◆

He slapped me on the ass calling me “morenita”

and I thought Well, that’s a relative term. At five years old, his little sister, Esme,

already knew that lazy meant “nigga” like his mother

knew to clutch her money close around los negros. Apparently, in 2017

I could still be “pretty for a Black girl”, “shyer” than expected. My suegra

asked if I wanted a seat on their trip to Mexico and I was so scared

that she might’ve actually meant how I’d be paying for my seat that I didn’t

know how to answer in my half-ass, textbook Spanish to her quick MexiCali accent.

I met the rest of the family in Mexico who swore they aren’t racist,

where they want to touch my hair and I say “no”politely, with a self-conscious smile,

where the kids tell Raul not to tan his pale skin and laugh at “mi pelo extraño,” where I fall into the impossible fantasy of building a family with people

who don’t want me.

“Los morenos no tienen respeto,”

said the Uber driver on our way home from another Christmas party at

tío Francisco’s and while my ears are quick enough, my tongue falls short.

Then I lifted my head from my boyfriend’s chest in the back seat

of this racist uber who thinks Black people are “disrespectful” so they deserve

to be harassed and brutalized by police, to an expression

of manufactured confusion and hoping that I didn’t understand.

Later on, I thought of a few responses that I should have been able to use,

but got stuck wondering why no one from “mi nueva familia” defended me.

“pinches negros…” he went on and on…

What would they say about my daughter and if I never learned to speak?

◆

We ate whatever I wanted like usual because Raul hates arguing about what to eat and because I’m paying for it anyway. It was midnight and only Colonial Donuts was open so we got a half dozen doughnut holes to share and some warm beverages to keep us awake. He drank his coffee dark and I sipped heavily sugared green tea with notes of lemongrass. We drove to Lake Merrit to find as much privacy as one could expect from a public park. It was better than going home where privacy was impossible because my mom would expect the door to stay wide open or to his house where his “bed” was a coach in the living room. We got out of his bucket of a car, a ‘94 Toyota he named Dazey, and started walking toward the location of our first date. Dazey definitely helped us get into this mess.

“So what did you want to talk about?”

“I don’t know. Us.” I blew at my tea to avoid his eyes.

“Okay… well, what’s going on?”

“Nothing really…” You just dumped your load in me and now we have to talk about killing it, is all.

“Don’t make me keep guessing.” All the playfulness fell from his eyes and he was no longer smiling. We stopped walking. The tree we kissed under on a similar rainy night four years ago was just around the bend of this hole-ridden pavement path. I looked at the large motherly Oak tree and said a quick prayer for her guidance. She seemed to look back at me, through a moonlit rustling of wet leaves, with melancholy. “Aliyah,” he said, irritated at my hesitation. A warning of his quickly boiling anger.

“It was positive.” I blurted out. “My test. I took the test today. Twice. I’m sure of it. I knew there was something different going on with my body. I just… I just didn’t really know what. And…” I trailed off on some nervous ramble. Raul stared ahead at our Oak tree that I just prayed to. He looked troubled and pained but, also there was something else in his body. Something dormant and secret that came alive in light of this news. Something whispered between lovers under cheap cotton sheets, atop lumpy synthetic pillows. A shameful desire. But, I was probably imagining things.

Even so, the message was clear. Whatever I roused in him would be put to rest without acknowledgement. We were two broke college students in our early twenties, still living with our single mothers (and siblings that somehow became our own responsibility too). We would both be the first in our families’ to graduate, if we just managed not to fuck up. Silence weighed heavily in the damp air.

◆

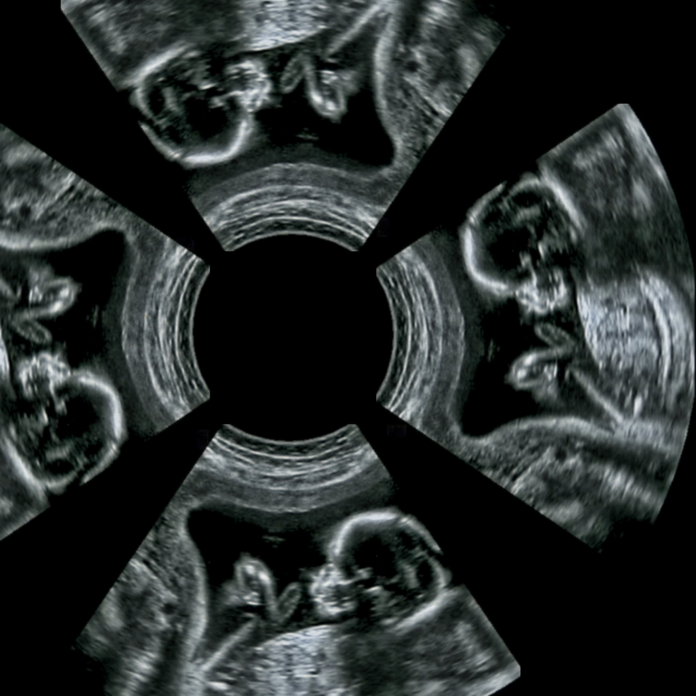

At the clinic, they shoved a dildo shaped sonogram machine in between my legs. I was six weeks. I asked for the pictures. Do I have to pay for those too? No, but it’s unusual for women to even look at the screen, let alone to ask for this keepsake.

They gave me pills after I gave them weeks worth of my labor in dollars, unaccompanied by the expected compensation due from an equally responsible “partner” in such a situation. Apparently, “money was tight” so Raul could not afford to confront the consequences of his actions, yet I could. Somehow.

I can’t undo this decision, they warned me. I knew that.

They made me take the first pill, labeled “mifepristone,” in the office as they watched. It was a small round thing, white in color and chalky against my cheek. That’s how they make you take it. Hold it between the teeth and the cheek for a few minutes and then swallow it down with some water in the ceremonial paper cup under the silently shaming hospital lights. Then, they sent me home with the second pill, misoprostol, in a brown paper bag. I promised to take it at home in 24-48 hours. He watched me carefully. I went home so high off the narcos they gave me that I couldn’t think about how horrendous or frightened I felt nor remember where I’d put the damn sonogram. I just remembered how alerting the the “fuck” was when in “What the fuck?!” when I asked Raul, after he picked me up from the women’s clinic, if he wanted to see her picture.

In the aftermath of it all, he effectively admitted that my dream of having beautiful, brown babies was mine alone. That I was delusional and he never intended to marry or have children, least of all with me. That he didn’t actively encourage the idea when we made love and if I thought he did, it was because I wanted to hear it.

But, certainly, he could not deny the reality of my pain in losing my child. I was deliberate when I said “I wouldn’t make a man into a father who doesn’t want to be one.” Those words clung to him. He did not enjoy their company.

No, he could not deny my pain, but he could absolutely ignore it though, leaving me to bleed out on my own, clutching at my belly and curled inward on myself, like a cinnamon stick.

Every few minutes, I was on the toilet watching love and guts falling gracelessly from my womb. And as I witnessed the gradual, seemingly unending shedding of my uterine lining into thick, oversaturated maxi pads, sharp pains splitting me open right down the middle, I wanted to pick up and open the soft, gel-like, maroon menstrual tissue, blood clots and all. I had the urge to find the formless spec of life in all that warm, wasted motherhood and calmly walk it over to him, in cupped palms, and say, “What a waste!”

But, what an odd thought that was.

◆

Rolled up in a box of paperwork from previous tax years and ex-employers, I find a thin, glossy film depicting my very first child. It’s so inappropriate, apathetic really, and the last place I’d put something like this. The sonogram is warped into a cylinder-like shape due to the fragility of the film they use at the clinic and my own negligence. Ceremoniously, I thumb over the edges trying to smooth it out and read.

FPA WOMEN’S HEALTH OAKLAND OBGYN

04/09/18

2:25:45 PM

7 cm/11 Hz

GS 1: 1.53cm

GS 2: 0.90cm

GS 3: 0.83cm

Mean GS: 1.09cm