1.

When I think about dusk, I think of the air and the feeling in my stomach. Like a knot but sore. Sore-sick. Dusk-sick.

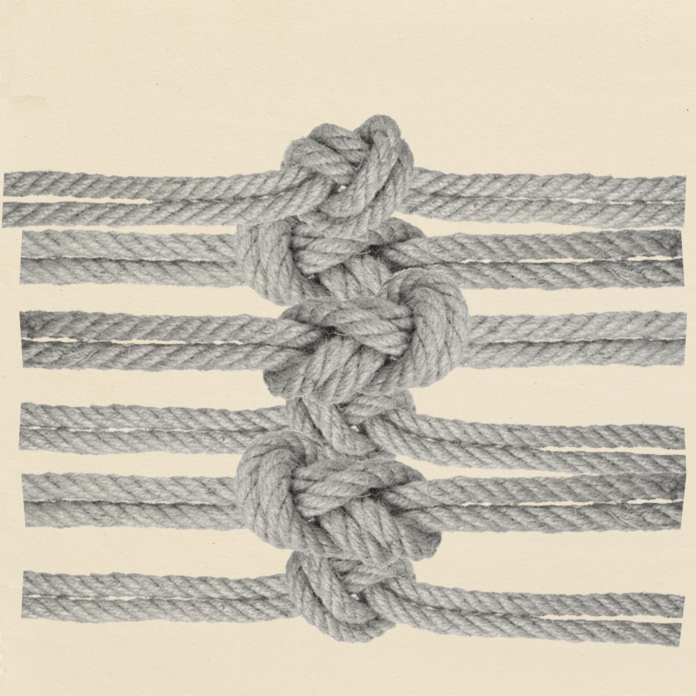

I think about reading all day on the couch, next to a tower of Nancy Drew books from the library a sweltering walk away, the AC cranked up. I’m in elementary school. Middle school. Boxcar Children. Stacks of Sweet Valley. Under a massive duvet, sunk into the couch, book after book while a beautiful summer day blazes outside. I am crammed into the deepest corners of the couch. Then dusk comes, and at first I think I’m hungry. Then I feel a knot.

I can conjure the stomach knot, the dusk-sick, just by thinking about it. It still comes. Cures include going outside; not realizing it’s dusk; not remembering the infiniteness of possibility and every thing I might have done compared to the things I did not do.

When I try to describe dusk, I describe it as personal and physical, not a time of day but a thing happening to me, as dusk-sick. I don’t know how to say what dusk itself is.

2.

Sometimes I get dusk-sick before realizing that outside it has turned to dusk.

I think I’m hungry, or dehydrated. I pour a glass of water or brew tea. I forage for a snack. But water or food doesn’t fix it. I sometimes think, “It’s getting darker. I should lower the blinds soon.”

I think this without realizing that this puttering thought coincides with abdominal discomfort. I am slow to learn, to remember.

The fiercest dusk-sickness comes after long and tedious work. Sifting through endless web pages. Multi-tasking pointless projects. It strikes, too, in guilty and frittering moments. It’s worst when I am not satisfied, or know I should not be satisfied, with what I have to show for myself after a day’s work.

Sometimes it creeps up when none of these things have been on my mind, and I haven’t been trying to get anything done.

Sometimes it makes a slow-motion, airborne, sideways leap and smothers me. I’m focused on a project and then wham–like looking up to see that hours have gone from the day–I feel that roiling wave in my gut.

It helps to leave the walled-in, indoor world and go for a walk. It helps to close all the blinds—even if it is not yet dark—and turn on all the lights and tell myself that dusk has passed and now it is night.

When I was a kid, I went through a phase of thinking bananas helped.

Sometimes I time a shower for dusk: I go in when it’s daylight out, and by the time I’m done, poof—the world is an easy twilight.

3.

When I was a kid, I liked to scare myself. I was good at it.

I tried to get lost in the woods near my house. Over and over, I tried to get lost.

I swam underwater in the community pool, when the sky had just turned dark enough that the lights came on below the water’s surface. I told myself that I was swimming along the side of a huge ship, too vast for me to take in the whole of it, and that the round lights in the walls were portholes. This portal, this fear-fantasy, gripped me every time. (I didn’t know the word for it: “submechanophobia.” The fear of partially or fully submerged man-made objects.) I’d convince myself it was real, and then I’d let the fear swell inside of me until I thrashed to the surface, kicking with panic.

Once my head was above water, I was out of control for a few seconds, desperate to get away from the lights in the walls, so scared that my limbs forgot how to swim. I needed the walls and I couldn’t escape them. I felt the undertow of the ship, tugging at my toes.

And sometimes, in bed, I would feel myself going still. There was an internal gravity at the base of my sternum and equally taut between my front and back ribs, pulling the rest of me ever inward, tighter, together.

Before I felt the fear, I was attracted to the thought that maybe I couldn’t move. I felt rings around my eyes tingle with pressure. I heard my parents, in the adult world, moving about other rooms. I wondered if they would check in on me.

(My brother, elsewhere in the house, in his bedroom, was also lying on his back, unable to get up or walk around. But his motor nerve cells had always foiled him.)

I felt my muscles, my bones, harden into stone, round and polished. I heard adult voices from other corners of the house. I knew that if I tried to call out, my throat would fail me. I knew no one would come. It was no longer light out; the day had flipped into nighttime, after all. And who would ever think to worry that a child had turned to stone?

4.

During dusk things get softer. There’s light but no visible light source. It sets a fuzzy lens over everything. Just a light grey. Color has been sucked out of the world like marrow from a bone. It’s a muting, a depletion. It’s the whole world gone pale with dread.

Dusk is eerie because of its anonymous illumination. I can feel the dimming, but there’s a bright glow: a white-grey, a soft light. Which sounds pretty; but the thing is that I’ve lost something.

I don’t just mean time, although I do of course mean time. The vivid greens are toned down. I’ve lost color, a feeling of the air alive, that sharp daytime taste of bitter and bright. I don’t yet have night’s calm. It’s like a crowded, bustling room where someone turned off the music and I only just noticed that it’s gone.

Something has disappeared before I knew to mourn it.

5.

I once wrote a dystopian city where people could only go outside during dusk and dawn. The rest of the day and night, the air was toxic. I never came up with a good reason why: As a conceit it felt immediately plausible to me; its logic already ran in my bones. I couldn’t motivate myself to justify a notion that was so apparent–that dusk is unlike any other time of day.

My characters were tweens, humans teetering in that exact space between one thing and another, people who at every turn could tip back into childhood or spill forward, older, a part of themselves gone. They were homesick runaways and leery friends, kids who had eschewed the world and now desperately needed each other. I loved their precariousness; their vacillation between the various selves they might become.

With the onset of teenage years, these children slowly lost the ability to see color. They missed it violently. It drove them to drink glow sticks; break fingernails to pry open batteries; sit motionless in oily, rainbow-swirl puddles.

One boy, still at home, sometimes held a kaleidoscope up to his cousin’s eye and slowly twisted its base like grinding a pepper mill. His catatonic cousin never moved. But the boy was sure that he liked it; he thought he saw a glimmer of response in his cousin’s eyes.

He did not consider this wasted time.

6.

I must be productive. I must create. Produce. What I make equals my worth. This is ingrained in me. The language on my tongue reflects these ideas.

Writer’s block: the writer cannot produce words. A dry spell: figuratively when you don’t have cash or sex coming in, but literally when the rain prevents crops; no rain, no bounty or harvest. A person’s worth is a dollar amount. A one-hit-wonder didn’t amount to much. Burning out is a personal failure.

Working at a nonprofit in direct service, I needed to move fast, pack in client appointments, and help as many people as physically possible in the very limited hours in a day. But now, when I write as quickly as I worked before, I produce the written equivalent of compost slosh. Slowing myself down takes more energy than I have some days. It relies on fighting more than momentum; going slowly grinds against the constant call to work harder, faster, more.

7.

In high school, on the road cutting through the woods in which I used to try to get lost, I drove too fast around hairpin turns. I saw it as a singular luxury: releasing myself from all responsibility to take care of my life; suspending that duty for a treasured handful of minutes.

In college, I found fun in darting across busy Chicago streets. I waited for the lull in traffic to pass, until there were a good handful of cars on the road, and then made my move. The space between cars felt like an expansion of time: There, on the yellow line, in the middle of what had looked like an unbroken stream of traffic, the world seemed to freeze.

Other days, I stood on the very edge of the platform as a train arrived, waiting for that woosh, the slam of wind that knocked into me when the first car shot past. I marveled at how little space there was between the train, bullet-fast; and my body, still.

8.

When I was twenty and unafraid of anything but insignificance, more fragile than I would have ever believed, I took hallucinogens just before dusk. I wandered alone, the sun sinking slowly like a hard red candy edged in gold. I couldn’t suppress the eruptive giggles, so I held a phone to my ear while I walked. I passed through famous streets I’d never seen—in Beijing, New York, Hong Kong—and through the worlds of books I’d never read, through tunnels lined with bright-colored cartoons, looming tall buildings, a space larger than I’d ever known could exist–I’d never known it was so big inside my head. This brush with enormity, so large I couldn’t fully see it, couldn’t fully take it in, held that elusive in-between that tingled my skin: Here I could glimpse one tiny corner of the immensity of everything that could happen inside of a mind, and, as with the portholes of a giant imagined ship, in glimpsing the tip of its buried depths, there ran an undercurrent of terror.

In my notes, I wrote: “Can I go back if I want to? The colors are gone.”

There was the pleasant zip of danger, the line-testing I’d played at so many times as a child, in the pool and alone at night in my bed. But by the end of the trip I couldn’t move. At one point I called out for help—I surprised myself by managing it—but that used up whatever I had. When they came, I couldn’t tell them any more information. I couldn’t move. They wandered away. I couldn’t watch them go because I couldn’t move my eyes. Eventually I fell asleep. For years afterwards, when dusk fell, I felt weighted with dread.

A year later, I egged my younger brother into skiing too fast down an easy ski route. I was bored; I’d never liked skiing, except for those moments when it seemed I was both immobile and airborne; that suspension of time and gravity. When, as we sailed down the icy slope, a woman stopped in front of me, and I twisted and fell to avoid her, and when I heard the crack of bone in my leg, I felt a tiny ripple of relief:

Well, I thought, so this is where it all stops.

Then I screamed. Because, I figured, it was the fastest way to tell everyone else what I’d just learned.

9.

Many animals come out primarily at dusk. Those with this tendency are called crepuscular, and include deer, capybaras, and ocelots.

Domesticated dogs, household pets, are known to get “zoomies” in the early evening. They tear around the house, senselessly sprinting and leaping, crashing into furniture and people. It looks like they’re using up a surfeit of energy; like they’re shaking off a day’s worth of ghosts. Some trainers call it the Witching Hour, when these human-adapted quadrupeds loose themselves upon vacuumed carpets and painted walls.

It might not come as a surprise, then, that wild dogs are also most active at dawn and dusk. So are stray dogs, the ones without homes; bereft of human structures, they return to ancient rhythms.

10.

I was fifteen miles into a long day on trail in Virginia, just north of the Shenandoah range, when it was clear that shelter was too far behind and too far ahead. As dusk pulled itself across the sky and through the trees, I learned that I could fly. My sore feet lightened. I glided down the trail, past terrain increasingly inhospitable to the tent on my back. My companions insisted on stopping to look at a map. I felt the tugging kite strings of freedom. I said: Let’s go on through the night.

Among the trees, it can seem like the rest of the world has already fallen into night, but, for some reason, beneath the boughs, there’s a stay from the onset of dark. If you look up, you realize that the sky is darker than the air around you; that it is later than you realized; and yet—sinisterly—you feel caught in stilled time.

In the woods, dusk creeps in slowly. Eyes adjust. The forest floor gets a misty, welcoming, specious glow. It is a lure. It suggests there will be time before night falls. Do not believe it.

You can walk to stave off the dusk-sick, but you’ll need to find shelter before it’s over.

On mile twenty-one of a long day in New Hampshire, my skin burned to bubbling from exposure in the granite-stepped Whites, I was back below tree line when dusk came. There were miles to go, and they were miles downhill, down a long path to the lone road that snaked through the range. This spoke trouble; my descents are slow and laborious. We had one set of poles between two of us; we’d learned on mile six that we both needed them.

It felt like a countdown clock had started.

I have never felt so long a dusk. It stretched into twilight.

But the anatomical magic of the human body adjusted our eyes incrementally. Light faded as our pupils grew to take more in. When we reached the road, it was full night, but we could see. We hadn’t even taken out our headlamps from our packs.

On the drive home in darkness, we felt like we were moving at light speed, so fast it must be illegal, and in fact it was: We were going twenty miles an hour in a forty-five zone. Even so, I’ve never known such momentum. As I reeled and swayed with nausea, I marveled at how we flew through the quickening night.