At 18 weeks, Wilder is the size of a disposable camera. At least that’s what my pregnancy app says. When I tell you this, you rattle off a list of vegetables he is comparable to: an artichoke, a bell pepper, a sweet potato. Those are all different sizes, I say, unsure whether I’ve seen an artichoke before. A quick Google search tells me an artichoke is one of the most elegant vegetables. I’m not sure what this means but I imagine our baby boy twirling inside you, like a ballerina in a snowglobe.

My mom has come a long way since I first came out to her. Well, since my brother came out to her on my behalf. I’d been too nervous to do it myself, and he obliged. He is famously terrible at keeping secrets and I didn’t want him to have to fumble through a lie to my mother when she called and once again asked, Do you know if Ris is dating anyone?

I was dating someone, a woman someone.

You weren’t even brave enough to tell me yourself, she said into the phone. She didn’t reject me, which I do feel grateful for, but she did invalidate and ignore—for years, she pretended I didn’t date women. She didn’t ask the questions I wanted her to ask: Are you seeing anyone? What is she like? Does she make you happy? What are her favorite things? Do you two have fun together? I wanted to have the type of relationship with my mother that involved giggling and gossip. I wanted her to fawn over the women I dated the way she’d fawned over my ex-boyfriends, using words like perfect when they were average dudes with average haircuts and average personalities.

Now, she calls me and talks about moving out West to be closer to my family. We want to come to his basketball games. Pause. Or his ballet recitals, she says, as if she has had a peek into my imagination. I can hear her grinning through the phone. She is proud of herself for understanding that hobbies and preferences aren’t assigned to gender, that our child can be whoever he wants to be, do whatever he wants to do, that he may be assigned male at birth but that doesn’t mean he has to be a boy or a man.

Frankly, I don’t care much for the vegetable size comparisons. I like the disposable camera best. It feeds my pathological sentimentality. The camera reminds me of high school, of early 2000s parties and vacations and school dances, when my friends and I had to wait a week for the film to be developed, only to find out that half of our photos came out blurry or underexposed, but there was always that one perfect picture that made the wait worth it. For me, that perfect picture was always the one that came after we’d all had a drink or three and temporarily paused our individual performances, of coolness, of humor, of confidence, and in my case, straightness—performances of whatever we thought would protect us, would make us loveable, and if not loveable, then at the very least, palatable.

I am so willing to romanticize the past but, if I take a closer look, all I see is shame and secrecy. The shame that silenced my desires and fueled my performance of blending in, of pretending to want what everyone around me seemed to want. I felt unlucky; I felt alone. I wish I had known you as a teenager, maybe played against you in soccer and felt, upon seeing you, that peculiar prickle of recognition that comes with queerness, with difference.

◆

All of my childhood best friends live on the East Coast. We’ve always got a group chat going, and we schedule periodic Zoom calls to catch up. But there are things I have kept from them over the years, ever since I realized I was queer, at age 16.

They, of course, know I am married to a woman; they were at our wedding, they are supportive. But I’ve never gone back and corrected my history as they remember it. Before the call, C was on Facebook and sent us a photo from that day, twelve years ago. It was a photo of us from our high school’s senior ball. Make-upped faces, fancy dresses, uncomfortable up-dos. Ris, who did you go to senior ball with? I forget, C asks. Paul, I say, remembering how I chose to go with one of our guy friends instead of take my secret girlfriend at the time. She’d been my first girlfriend ever. She was two years older than me. At the dance, I texted her, I wish you could be here. Not, I wish you were here. Every time I saw her, I lied to everyone about where I was and who I was with. It was a beautiful, agonizing year.

Photographs are some of the best liars I know.

If I were to scroll through my Facebook back to 2006, when I was 16, I would find lie after lie. Boys I was dating, boys I went to dances with, boys I met on vacation with my best friends. My Facebook photo collection is an alive thing, a desperate, snarling artifact.

Even throughout college, when I was out to all of my college friends, I didn’t post photos with girlfriends. We were in group photos together but I never made my romantic life public. I never posted a photo with my arm around a girlfriend, I never wrote a caption that could possibly allude to a romantic relationship with a woman. My excuse, at the time, was that I was a private person; people didn’t need to see that part of my life. Posting a photo with a girlfriend felt like coming out to the world. I only wanted to be out to my small, gay, jock microcosm, where I knew no one would judge or reject me.

Since I graduated college, I have become increasingly sick of the false history in my photos—why do I keep them? Whose story are they telling? But since meeting you, my relationship to photographs has changed.

Now, I take and post so many pictures of you that it borders on worship, but I don’t care—I want to have as many photos of you as possible before this all disappears.

This as in, you and me and Wilder Fox.

Disappears, as in fades, as in retreats.

◆

When I tell you that I ordered prints from CVS and two old-school photo albums—one for us and one for Wilder—you laugh and ask when I transformed from a 30-year-old into a 60-year-old. You understand, though, how phones can become a black hole for memories. Rarely do I scroll back through old iPhone photos. And much like physical books, I’d rather hold a photograph in my hand. I want to feel the weight and heart of it, its delicious thump, thump, thump.

When the photos arrive, I ask you to put our photos in our album, in order. It is one of those albums that has an adhesive page with a plastic covering that goes over it. Within seconds, you grow frustrated with this imperfect method of recording our history. You work and work at it, while I play video games and watch you out of the corner of my eye.

When I was young, I was obsessed with watching home movies and flipping through my baby book. I thought, how could these things have happened if I don’t remember doing them? Now, when I look at early photos of you and I, I think, how could this be happening in my past, present, and future all at once?

Dozens of Polaroids are scattered all over my desk, with faded sharpie labels of where and when the pictures were taken. Australia, 2017. Ocean Beach day, 2018. CDMX, 2018. Cinque Terre, Italy, 2019. Joshua Tree, 2019. Lord Huron (no date).

Sometimes the wind enters the nearby window and rearranges them like autumn leaves.

It is like watching the entire history of us perform all at once.

I am convinced that, to a certain extent, there is nothing humans are more afraid of than their own happiness realized.

What do we do with happiness once we obtain it? What if it shape-shifts? Evaporates? Loses its memory? Catches a last-minute train home? All I know is, I am so in love with you that every day, I force myself to practice losing you. In my mind, it is the only way.

◆

When my father retired, he took up photography. He takes photos of lakes, mountains, deserts, and beaches. He takes photos of robins and blue jays in the backyard. He goes on weekend photography retreats with professionals and learns how to take photos of the night sky. Whenever I talk to him, he tells me about his camera and the fancy lenses he bought. He tells me how his camera automatically syncs the photos to his phone, shrinking them so he can share them with my siblings and I. This type of technology is absolutely astounding to him. When he speaks about photography, he glows with pride and joy, and I think that I could die happy as long as I know that my father is happy.

That tenderness for one’s parent, will Wilder feel that?

I don’t feel different since becoming a parent-to-be. I think of Wilder the same way I think of you and other people I love desperately: I never want him to feel obliged to love me, I merely want him to choose me, if he wants, over and over again. Of course, it’s a selfish desire. But you and I, I know we both long for that decisiveness; we both know the word family is more about autonomy than circumstance.

My father recently gifted me his 35mm film camera—a Pentax K1000 from the 1970s. He and my mother had received it as a wedding gift. When I see him, he tries to teach me how to use it, knowing film is a foreign language to me. I take blurry photo after blurry photo as I practice. I don’t care, I don’t want to look up how to do it. I want to learn by taking pictures of everyone and everything that stirs my insides up. Every time I see him, he tells me the same story: when my parents first started dating, they went to the beach with some friends. It was nighttime. My dad wanted to take a picture of my mom, who was standing at the water’s edge. He set the shutter speed at the highest it would go, then set the camera on a bench so he wouldn’t get any shake. The photo that resulted was the photo of all photos, the subject was beautiful and unaware, the artist was in love and documenting it.

I know you are sick of being my subject. Every time I hold the camera up, you grow embarrassed or frustrated or both, holding a hand over your face and muttering how you look gross. We don’t need documentation of you working on the couch or watching TV or watering the plants or drinking a sparkling water or shoving ice cream in your face. But just because we don’t need it, doesn’t mean I don’t want it.

When we first met, one of the first things you texted me was, You can text 572-51 with the words “send me” followed by a word or emoji or whatever and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art will send text you a piece of art that fits that description. I thought you were playing a prank on me. Are you serious? I asked. Yeah, you said. I tried it out. I said, Send me romance, and the SFMOMA sent me a black and white photograph of a man and woman kissing on the carpet of their house. The museum was right—I felt romantic just looking at it. I knew I was in love and I knew it was with you. I still have that photo in my phone. It makes me want to buy a carpet for our living room.

My dad no longer likes to take photos of people. He takes photos of anything but people. Animals, landscapes, skies. He tells me he has a software that can remove people from photographs. He says this like it is a lovely thing. The very thought spooks me, but I don’t tell him that.

Disappear, as in delete, as in never was.

I don’t know what it is my dad likes about photos without people in them, but they seem to bring him a sort of meditative peace. He is most himself when he is photographing things that do not belong to us. Of course, people do not belong to each other, but that’s not how many humans behave. You are mine, I catch myself saying while we cuddle in bed. It is a trite way of saying, I love that you love me even though you don’t have to. That element of choice is what I am after, what I cling to. There can be no true ownership if we grant permission to be owned.

Oftentimes, whether in social situations or just with you, I don’t know what to say. Or, I think so hard about words that none of them seem right. I like to participate from behind a camera. When we go camping with our friends, I will watch everyone sit around the fire. I will watch everyone hike and climb. I will watch them laugh and play with their children.

The trouble with words is they mean something different to everyone.

So sometimes I do not speak. I don’t need to. I examine you and everyone we love through the lens of a camera I barely know how to use. I try, and often fail, to capture the life around me. But for a few, delectable moments, I feel like I can see everything.

◆

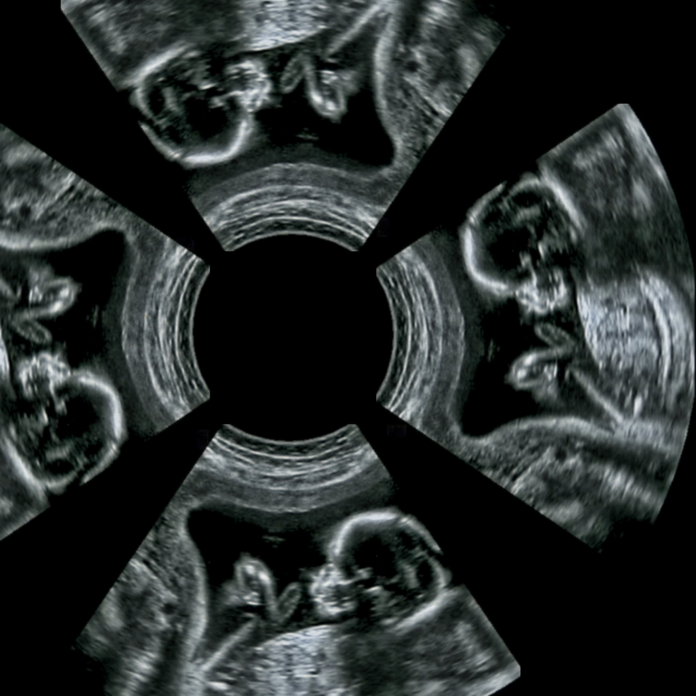

Despite the name, I always assumed an ultrasound was a camera—how else would it create a visual of our baby? Apparently, it uses high-frequency sound waves to create video. The first time we heard Wilder’s heartbeat, you laughed maniacally, shocked that your body could give way to another body. And the shock hasn’t waned one bit—every ultrasound, we are all wows and holy shits and did you see thats all over again.

Wow, as in, what is the language of awe?

Holy shit, as in, keep the film rolling.

Did you see that?, as in, Who is this person and will photos ever be enough to know?